Fantasy, fable and folktale

Tom Knechtel displays his yantra drawings at Cuesta College

By Ashley Schwellenbach[{

"name": "Newsletter Promo",

"id": "NewsletterPromo",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "4",

"component": "15264767",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "0"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

If you swept the contents of an artist’s imagination and subconscious, the emergent gelatinous wad might resemble a painting or drawing by Los Angeles-based artist Tom Knechtel. Men, bells, cities, weapons, horses, snakes, dogs, blowjobs, trees, and even pineapples are among the fantastic forms that ally to create new folktales and myths, narratives particular to Knechtel’s experiences.

“I think drawing is really a form of thinking,” explained Knechtel. “And I like seeing the way people think.” And though he tends to regard his paintings as “large, sprawling—like operas—big theatrical things,” Knechtel’s drawings begin with a single form, generally a human or other type of animal, before descending into chaos, at the reins of his associative thought pattern. He’ll begin by imagining the spectacle of a house on chicken legs and conclude somewhere else altogether.

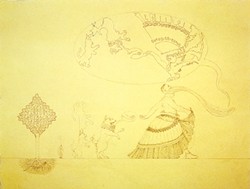

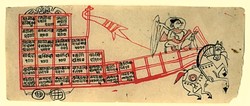

But in his drawings currently on display at the Cuesta College Art Gallery, Knechtel derives inspiration from his collection of Indian yantra drawings. The purpose of such images is to walk a devotee through prayer or meditation. They employ such symbols as lotus flowers, swastikas (which denote welfare, good luck, and prosperity), as well as geometrical patterns. One image in his collection features Hanuman, a Hindu god who famously led a monkey army against the demon King Ravana, surrounded by textual prayer. Artists often create yantras, as do priests, and devotees. While Knechtel can’t understand the Sanskrit or Hindi scripture laced throughout the yantras, to him the images convey a wealth of meaning.

In particular, Knechtel appreciates the extent to which yantras utilize narrative, a combination of eastern aesthetic and storytelling that hearkens back to his childhood fascination with One Thousand and One Nights.

“Part of what I liked was the sprawling stories within stories,” he explained. “I love narrative. I love reading and I’m very engaged by how narrative works. I think storytelling is interesting when it’s sort of spiraling about.” For Knechtel these stories simply happen to carry an autobiographical edge, his paintbrush or pencil burrowing into the depths of his fantasies. And though he insists he is not a realist in any sense of the word—citing a compulsion to create art that is full of life without replicating life—Knechtel believes that drawing from his own experiences enables him to convey a sense of humanity and life to viewers.

To support this opinion, Knechtel cites a children’s book illustrator, who criticized the fact that his contemporaries generalized about how adults think children should think rather than relying upon their own specific experiences of childhood. His own work carries an unnerving fusion of childish fantasy and adult preoccupation, sexual acts within the confusion of a circus-like spectacle.

“I’m kind of hard-wired both for a kind of fantasy that I think is childish and also sexual content,” he explained. “I try not to have the image be too titillating but the structure of my thinking is very much like the structure of folktales. I think that kind of territory that children’s literature has had to inhabit, for better or worse, is very natural for me.”

Being a middle-aged gay man encourages Knechtel to explore sexuality; in some of his images he presents sex as a mere act, removed from the softness of romance or familiarity of domesticity. But he restricts these depictions to a single corner of his drawings, doesn’t allow them to escape and inhabit the entire canvas. Knechtel’s renderings lack the moral payoffs that riddle the narratives that most fascinate him. Not for him the self-righteous epilogue punishing the wicked and rewarding the virtuous. Instead, Knechtel resists drawing conclusions for his audience, accepting that even within his darker work there’s an ecstasy in ferment.

Although Knechtel doesn’t pay tribute to realism in his work, there’s no denying that the realities of day-to-day life intrude upon his art. He carries his cat into his studio, and listens to music while he paints, though he prefers silence while drawing. He knows, however, that if he gets too dependent upon a particular routine, it may become an excuse to avoid getting down to the task at hand. There’s always something else—errands, a trip to the gym, technological correspondence—that could occupy his studio time.

“I think the challenge is to keep going into the studio and creating,” he concluded.

Arts Editor Ashley Schwellenbach prays to the goat gods. Send bundles of sacrificial grass to [email protected].