[

{

"name": "Promo Temp Targeted",

"id": "PromoTempTargeted",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "4",

"component": "15511697",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "0"

},

{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250 - Inline Content",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "15582119",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250 - Inline Content",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "15582122",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle 9 - 300x250 - Inline Content",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "15582121",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

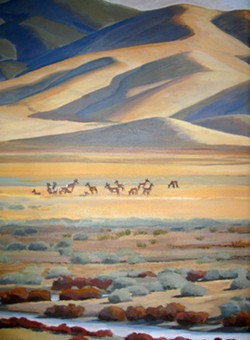

It’s a scene that could have happened during the ice age hundreds of thousands of years ago—or today, just an hour’s drive from San Luis Obispo.

Graceful pronghorn antelope move slowly across the vast plain, munching on the tender leaves of flowering plants emerging among the grasses. Startled by the distant approach of a predator, the whole herd takes off running, leaping along in perfect unison, fleet as the wind.

In the Pleistocene epoch, pronghorn antelope had to outrun cheetahs. Today, the threats these remarkable creatures face are even more daunting. As few as 10 percent of the antelope fawns born in SLO County survive to adulthood, research shows.

“They’re incredible animals,” said Bob Stafford, a state Department of Fish and Game wildlife biologist who’s been keeping track of the pronghorn living in the Carrizo Plain in eastern SLO County.

“It looks so effortless when they’re running 30 or 40 miles an hour,” Stafford said. “They don’t rumble past like a herd of elk. With these guys, it’s almost like the wind, they pass you so quickly, without a sound.”

Built for speed, local wild pronghorn antelope are the fastest land mammals in the Western world, clocked at up to 70 miles an hour. About five feet long, the ruddy-colored animals weigh 90 to 130 pounds and stand 2-1/2 to 3-1/2 feet tall. A distinctive necklace of white fur emblazons their chests, and their rumps and bellies are white, too.

“It’s a very unique species, an ancient animal, a Pleistocene animal. They have neat adaptations that play a role in their survival,” explained Diego Johnson, a graduate student who’s studying the survival rates of pronghorn fawns on the Carrizo Plain.

“These guys evolved to run,” Johnson said, detailing their adaptations: sleek bodies, long legs with a unique bone structure, large lungs and heart. Their front hooves are enlarged, and their back hooves have a cushion of spongy tissue that acts like a spring.

But living on the wide-open North American plains of an ancient age, they didn’t evolve to jump. That’s one drawback that makes living in the Carrizo a little problematic for these born-to-run animals, due to a human creation: fences.

An extensive network of barbed-wire livestock fences crisscrosses the Carrizo, making it difficult for pronghorn to move between foraging areas. Crouching low, they have to pass under the barbed wire, since they aren’t built to jump over even low fences.

According to Stafford, pronghorn numbers seem to have declined since they were reintroduced to the Carrizo Plain in the early ’90s, as were the more successful tule elk. A continuing drought probably hasn’t helped pronghorn survival, but fences make their lives tough, too.

That’s where volunteer labor comes in. Craig Deutsche of the Friends of the Carrizo Plain is one of many volunteers who work with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management to remove or modify the four-strand fences on the 200,000-acre Carrizo Plain National Monument.

“In old-time history, cowboys were obliged to replace fences, and it was their least favorite job,” he noted with a little laugh.

Still, there’s nothing like the vastness of the open space around the volunteers, the big sky, and the thick silence. Sometimes they even see the pronghorn they’re working for, grazing off in the distance or making their way under a newly modified fence, fawns and all.

This year, 100 volunteers have put in a total of 900 hours and have modified five and a half miles of fences and removed another five and a half miles, according to the monument’s manager, Johnna Hurl of the Bureau of Land Management.

Altogether, 40 or 50 miles of fences have been removed or modified in recent years, with another 50 miles to go, Deutsche said.

For Jeff Kuyper of Los Padres ForestWatch, also a volunteer, it’s rewarding labor. “We’re out there getting our hands dirty. It’s a long, hard day of tedious work. But when you look out at an area where there’s no longer a fence, it’s a nice feeling to know pronghorn can roam freely,” Kuyper said.

The Friends of the Carrizo Plain plan to organize a fence-work project from Dec. 28 to Jan. 2 (full, with a waiting list) and again in spring, and Los Padres ForestWatch has a volunteer weekend scheduled every month through May. The local branch of the Sierra Club and the state Department of Fish and Game also organize volunteer work parties.

“Pronghorn get to a fence and don’t know what to do with it,” Kuyper said.

With their plains heritage, it’s not just fences that affect pronghorn. The sleek runners aren’t used to obstacles of any kind. They’ll avoid something they can’t see through, according to Fish and Game’s Stafford.

No one knows how pronghorn antelope will react if they’re forced to share their range with an extensive array of solar panels. One company has proposed erecting enough solar panels to cover several square miles, some where pronghorn often browse near the Carissa Plains Elementary School.

“The discussion on the solar projects may center on the pronghorn,” said Neil Havlik, a biologist who’s been chairman of the Carrizo Plain National Monument Advisory Committee. “It’s going to be shouted at the county [decision makers].”

Kuyper, too, is concerned about the possible effect of a sea of solar panels on the pronghorn. “Solar plants are being proposed in the heart of pronghorn habitat,” he said.

“Solar is a desirable form of energy, but we need to be careful where we locate industrial solar farms so we’re not trading one impact for another. Something of that magnitude needs close scrutiny. They’re going to have to figure out how to do it without impacting pronghorn,” Kuyper added.

Wildlife managers like Stafford are studying where pronghorn move as they search for suitable forage up and down the Carrizo and beyond, from Shandon south to Tejon. Scientists are mapping the different types of vegetation these ancient animals prefer—mostly forbs (nonwoody flowering plants), shrubs such as salt brush, and a little grass.

Stafford flies over the pronghorn herds regularly to check their progress, and has concluded that two distinct populations live in the Carrizo—one in the Highway 58 area and another in the National Monument and as far south as Cuyama. The idea is to provide a big enough area for pronghorn to run, from Shandon to Antelope Valley—“links to a chain, so they can move as conditions change,” Stafford said.

“The Carrizo itself might become drier and drier, so areas to the north, with more forage and more water, may become more important for them.”

From the air, their distinctive leaping gait looks effortless, Stafford said. “It’s incredible to me. They’re running 30 or 40 miles per hour. If we have to turn the plane around to follow them, they can be two or three miles away by the time we come back.”

Radiotelemetry collars using Global Positioning System tracking would help wildlife scientists follow their movements over time to better understand what they need for survival, as Stafford has found with the Carrizo’s collared tule elk. But it’s almost impossible to catch and collar an adult pronghorn without traumatizing it, Stafford said.

Grad student Diego Johnson has been implementing a different plan: Find the newborn pronghorn fawns in springtime, wait till their mother moves away to feed, and gently slip an expandable collar around their necks before they know what’s happening—and before they get fast enough to outrun him, at about 4 days old.

Working with the U.S. Geological Survey, he’s analyzing data from around two dozen collars he put on pronghorn fawns last spring. Johnson recovered the collars in the Carrizo after they dropped off the fawns, at about 4 months old. The collars show the fawns’ position every two hours.

“We’ve seen the pronghorn numbers steadily drop,” Johnson said. “The biggest issue is predation from coyotes. It’s normal with pronghorn for about 75 percent of fawns to get eaten by coyotes, but the mortality in the Carrizo is 85 to 90 percent. If they make it through those first two months, there’s a good chance they’ll survive.”

Finding the newborns in the vast open plain isn’t always easy.

“I always say I drive around looking for single females,” Johnson joked, because the pregnant pronghorn will break away from the herd before giving birth. He watches to see if he can spot a young fawn standing up to quickly feed before it drops back down into cover. When the mother walks off to graze, he moves in.

Weighing less than 10 pounds, the young antelope fawns aren’t speckled like a deer; their distinctive coloring is identical to their parents’. For camouflage, the fawns rely on remaining totally still.

“I’ve walked over a fawn four or five times before I finally see it,” Johnson said. “They’re completely motionless, thinking they’re hiding even while I’m putting the collar on. And they’re just cute as hell—they’re ridiculous,” he said, smiling.

Johnson is also looking at what type of vegetation seems to favor the pronghorn fawns’ survival by providing cover and forage, and what effect barbed-wire fences have.

A new resource management plan for the Carrizo Plain National Monument calls for maintaining a herd of 250 pronghorn by planting a mosaic of tall forbs, shrubs, and grasses for fawning cover and forage, plus providing water sources and modifying or removing fences.

“They are wild animals that you can see wild. It’s their country, and we are the visitors,” said Deutsche, the fence volunteer.

As Kuyper put it: “A lot of people don’t know we have wildlife like that, literally in our own backyard.”

Environmental journalist Kathy Johnston can be reached at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023 -

Cal Poly report highlights offshore wind's potential to spur green energy transition

Jun 8, 2023