[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

The drive to Stepladder Ranch and Creamery is a long and winding one.

Meandering along San Simeon Creek, this is one of those roads I have to take my time on. Agricultural land butts up against riparian habitat. Country houses and "no trespassing" signs line the paved byway as it heads into the hills outside of Cambria.

And when I finally arrive at the rusty red gate adorned with an iron-clad cowboy, I park and wait for the tour guide to arrive. Today, that guide happens to be Catelyn Willig, who's been at the ranch off and on for a few years and really loves goat wattles—those weird little tassels of skin and fur that sometimes hang down off goats' necks or ears. Heading through the gate and over the creek, I follow Willig's VW up the long drive and park in front of the big red barn.

More than 200 varieties of subtropical fruit grow on this land, which has been farmed by the family who's owned it since 1871. Buddha's hand, passion fruit, bananas, citrus, and a lot of avocado, among many other things, populate the acreage. It's all "part of diversifying the farm and making sure we can get all the use that we can out of the land," Willig says as I and the other tour attendees gather on the grass.

Stepladder also has angus cows and heritage pigs for meat, chickens for eggs, and goats for milk. I'm definitely here for the goats.

Willig leads us up to pens where the kids are hanging out. There are 107 or so of the little guys, who are about 2 months old. They've been weaned, and they're feisty. She leans over and pulls four or five over the fence to wander around and encourages us to pick them up. These Lamancha goats were bred in Oregon, she says, and they have unique features, including tiny ears "that look like tortellini, which is my favorite."

She's totally right. Their little ears blend into the side of their heads, giving them an almost alien shape—and I mean that in the most endearing way possible. They're even-tempered, an important thing when newbies are handling them on the regular. And Lamancha milk has a high butter fat percentage, Willig adds.

About five years ago, Stepladder added creamery to its list of outputs. It now milks 60 goats per day at 7 a.m. and 4 p.m., getting about a gallon of milk per goat, and turns it into a variety of hard and soft cheeses that run the gamut from fresh to funky. After a spin through the barn that holds the milking parlor and the cheese making facility, we get to the tasting room—which, let's face it, is really why we all came.

Stepladder produces more than the 10 cheeses we tasted, purchasing cow's milk from the Cal Poly dairy to supplement the goat and aging some of the goat's milk cheese so that it can be sold in the off-season.

The fresh chevre is where this place really shines. I can see the goats outside as I stick a sample size of the fresh, clean, creamy substance in my mouth.

It's a beautiful thing.

Facing decline

Although Stepladder was originally one of five cheese-producing creameries in SLO County, that number is down to three: Stepladder, Central Coast Creamery, and Farmgirl Creamery, all hanging on with no signs of stopping.

Their ranks once included Alcea Rosea Farm in Templeton and Rinconada Dairy in Santa Margarita up until a couple of years ago. In September 2017, Alcea's Bev Michaels announced she was retiring after 16 years of milking goats twice a day. And after 14 years of making cheese commercially, Rinconada Dairy Farm made the decision to retire the goat- and sheep-cheese making part of its operation the year before Michaels did.

Rinconada owner/operator Christine Maguire attributes it to two things.

"I got old and tired," she said with a laugh. "Well, that's part of it."

The other part has to do with antibiotic testing. Around that time, the state stepped up the pressure on antibiotics testing in milk. California, Maguire said, is pushing small artisanal operations like hers to test every single batch of milk for antibiotics. When you're a large commercial operation, going through thousands of pounds of milk every day, it makes sense, Maguire said—but for a small farm, that's not the case.

"When you're our size, you can't make cheese," Maguire said, adding that with small batches of milk, any antibiotics could kill the cultures used to make cheese. "If you put antibiotics into an animal, you take her out of the stream, and you never put her back in. That's just the way it's done."

With the looming expense of testing milk almost daily, either by sending it out to a lab or purchasing the testing equipment themselves, Maguire said her husband wrote a letter to the California Department of Food and Agriculture requesting that it make an exception for creameries of a certain size or smaller. The department, which didn't return New Times' request for comment before press time, declined to acquiesce.

"The margin in artisan cheesemaking is really small," Maguire said. "We just weren't making money, and that was making it worse. So it came at a good time for me because I was old and ready to retire."

The Maguires weren't the only ones to retire around that time. She said she could think of several others who made the same decision due in part to the testing requirements. Of course, Maguire didn't retire completely. She and her husband still raise chickens, heritage turkeys, lambs, goats, and pigs that are sold for meat, plus they operate a farm stay on their property.

"It works out beautifully, and it really did help out financially, and now we do it because it's really fun; we get to meet really wonderful and interesting people," Maguire said.

Adapting locally

Thirteen years ago, in 2006, Danika Gordon came back to the Central Coast and started peddling cheese out of a refrigerated truck. Pulling up to restaurants, she would invite SLO County chefs into the truck and do a tasting for them. At the end of the day, all of the cheese would get unloaded into the coolers that still hold cheese at Vivant Fine Cheese in Paso Robles.

Gordon laughed when she talked about the way things started out for the cheese shop and wholesale distributor: with a fanciful idea of selling all of the soft, stinky French cheeses to folks in North County. Paso wasn't quite ready for that kind of wine country experience just yet.

"We ended up throwing a lot of it in the dumpster," Gordon said. "The thing that's evolved over time with this is understanding what people will buy and what they won't."

Now, stinky cheese is definitely in. So are local cheeses such as those from Farmgirl, Central Coast Creamery, and Stepladder—of which you can find several peeking out from the stacks arranged just so in Vivant's front coolers.

"There's so little of it. ... Chefs are really surprised at that," Gordon said. "When I sit down with the chefs, we broaden our 'local' out a little bit so we have more to choose from."

At any time, Gordon said the shop carries about 200 types of cheese, rotating them in and out depending on the time of year and the season. Goat cheese, for instance, from places like Stepladder definitely depends on the season because goats only produce milk for a few months out of the year.

Although Vivant does move cheese out of the little shop on Pine Street, about 70 percent of Gordon's business is wholesale, selling local and nonlocal cheeses alike to wineries, restaurants, and shops. Whereas Fromagerie Sophie, a cheese shop in San Luis Obispo that closed earlier this year after five years in business, depended on foot traffic to move its 60 to 80 European, artisanal, and all around tasty cheeses, Vivant doesn't.

"The wholesale is really the key," Gordon said. "Otherwise you couldn't turn the product fast enough ... you couldn't have 200 types of cheese; you could only have 10, and that limits your clientele."

Wholesale was always the start and endgame for Gordon, who graduated from Cal Poly's dairy sciences program in the late 1990s and went to work for a Central Valley cheesemaker that specialized in selling tons of cheese in the Midwest. She sold cheese on the Chicago Mercantile, and traded by the truckload—40 pound blocks, 640 pound blocks, and 500 pound barrels of cheese—for about seven years before working for a company out of Green Bay, Wisconsin, as the director of West Coast Sales

"I was ready to not live out of a suitcase anymore," she said with a wry smile.

Gordon's family has spent generations in SLO County. She grew up in Atascadero, and her mom's grandfather made cheese at the Creamery (when it was a real creamery) in downtown SLO.

"That was, you know, when land was cheaper and more plentiful," she said.

And when dairy cows roamed free and creameries were all over the county. With land as expensive as it is on the Central Coast, it no longer makes sense to use it for cows that you have to keep close to home because they need to be milked daily, Gordon said. Goats take up less space and are cheaper to manage. Plus, cheese is expensive to make, and the margin on each little round or wedge isn't very high.

So, like any sort of artisanal agricultural endeavor, cheese is a tough business to be in. A little bit of luck and an ability to weather the hard times are essential. But Gordon said Vivant does everything possible to support local cheesemakers as much as it can.

"It's important because we're all in this together," she said.

Farmers and pallets

Rounds of Holey Cow are getting a wet, white plastic coating rubbed on them inside the nondescript industrial building that houses the Central Coast Creamery. This slows down moisture loss and enables the cheese to breath, creamery owner Reggie Jones tells me.

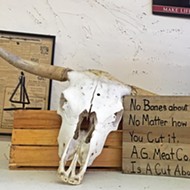

Holey Cow is "the only Swiss cheese made in California," Jones says. "When we're looking at what we're going to produce here, we're looking at what holes are in the market."

No pun intended.

The cow's milk cheese happens to be the top seller, and it's freaking delicious. I love Swiss cheese. I know it's a strange cheese for an American to obsess over. It's a little rubbery and it has a bunch of holes in it. Gruyere, a close cousin to Swiss, is also one of my faves. The slightly nuttier crunch of crystalized cheese just puts me over the edge!

Holey Cow tastes like Gruyere and Swiss had a baby. It's got a creamier mouthfeel. It's nutty, sweet, and soft—and I'm standing in a room that's stacked with shelves of it making their way from the floor to the ceiling. This yellowish cheese isn't the only delicious item in the Central Coast Creamery's temperature-controlled aging rooms.

There are nine others, including Ewereka, Seascape, and Goat Cheddar—all of which took home Best of Class awards in the hard sheep's milk, soft and semi-sweet mixed milk, and hard goat's milk cheese categories, respectively, in the 2019 United States Championship Cheese Contest hosted by the Wisconsin Cheese Makers Association.

Jones uses three milks in his cheeses, but he doesn't have cows, goats, or sheep stashed anywhere. He brings in cow milk from the Cuyama Dairy, goat milk from Hanford, and sheep from Lemoore.

Similar to Gordon at Vivant, Jones got his start at a large commercial operation in the Central Valley after graduating from Fresno State University. He made cheese for the largest dairy cooperative in the nation, the Dairy Farmers of America, dealing with more than 200,000 pounds of cheese a day. After that, he worked for a company that helped troubleshoot problems with cheese, working with bacteria cultures and figuring out flavor profiles.

"It's kind of a unique background to allow us to start up and start making high-quality cheese right away," he says.

Central Coast Creamery got its start in Oakdale in 2008 with the intention of moving to SLO County. Although, at first, the plan was to keep things artisan, he quickly realized that in order to be a viable business, they needed to scale up. He figured that out almost immediately, he says. Before they even installed the first vat they'd purchased, Jones says, they realized it wasn't going to work and they needed a larger one.

"We don't do farmers' markets. We don't do tours," Jones says. "We sell pallets of cheese to distributors. We don't do direct to wineries or anything like that."

Every day between 6 a.m. and 5:30 p.m., Monday through Friday, Central Coast Creamery processes between 1,000 and 1,200 gallons of milk that become more than 20,000 pounds of cheese every month. All of the milk gets tested on site for antibiotics, and Jones does testing for Negranti Creamery, which makes sheep's milk ice cream in Paso Robles.

The cheesemaking process here is continuous. Rounds of goat and cow milk cheeses are floating in a salt-brine, fresh off the cheese press, which is waiting to receive new curds to press. Whey and curds pour out of the vat into a contraption where the whey will drain out (and get sent to some hungry, lucky, and soon-to-be-delicious little piggies), and the curds will move on with their lifecycle.

Jones opens the door to a second aging room, and it smells distinctly different from the first. A little sweeter, a little less barnyardy.

He tests a wheel of cheese that he partnered with Firestone Walker Brewing Company to craft. It's a hybrid of sorts, and the curds were soaked in Mocha Merlin.

"Why wouldn't you put a milk stout in a cheese?" he asks.

Exactly.

Using a trier—yep, that's what it's called—Jones pulls out a small round column of the new cheese, which he says is almost ready. It's marbled brown and yellowish, soft in parts and crystalized in others. It's different. To me it tastes a little bit like yeast. Jones says he can taste the stout.

He talks about the process excitedly. After 29 years in the cheesemaking business, his passion for the craft hasn't waned.

"I like being able to create something from milk," Jones says. "I like the fermentation process." Δ

Editor Camillia Lanham took her time on the cheese beat. Send your comments to [email protected].

Speaking of Food & Drink 2019

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023