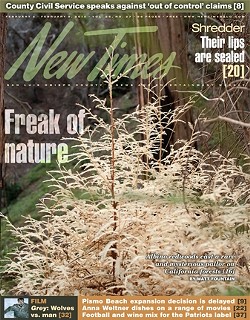

Phantom arboritions

Ultra-rare albino redwoods sprout close to home--but you'll have to find them yourself

By Matt Fountain[

{

"name": "Promo Temp Targeted",

"id": "PromoTempTargeted",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "4",

"component": "15511697",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "0"

},

{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250 - Inline Content",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "15582119",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250 - Inline Content",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "15582122",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle 9 - 300x250 - Inline Content",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "15582121",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

They can lurk in the shadows of the great coastal redwood.

Thriving in the dark and damp, and lying tucked away among the massive trunks of redwoods, they are easily overlooked by the casual passerby.

In many ways, the elusive and enigmatic albino redwood lives up to its nickname “Ghost Tree.” The ghosts, while not native to San Luis Obispo County, could be closer than you think—in the darkest corners of your favorite family campground, or peeking out along the side of your most frequently haunted hiking trail.

There’s more to the plant beyond its ghastly color. The unusual way it forms, the cannibal-like method by which it survives, and its tendency to vanish from certain locations one year, only to reappear in that same location in another, only adds to its intrigue.

Just how many of these ghosts exist in the wild is a tough figure to pin down. But according to the botanists, historians, and travelers who talked with New Times, less than 50 have been discovered throughout the native redwood regions of California and Oregon.

New Times took a trip not far to the north, to a dark, semi-secluded location in the Los Padres National Forest in Big Sur—as far as we can tell, the southern-most example of a ghost in the wild—to photograph one of the few known albino redwoods in Monterey County.

We are far from the first to note the existence of these eerie plants—the only white evergreens in the world—but their precise locations in the wild are something of a closely guarded secret among those in the know.

But despite the secrecy and concern over their survival, the albinos continue to attract curious visitors year after year, and seem to dispel the well-known comment made in 1966 by then-Gov. Ronald Reagan, at the time opposing the expansion of Redwood National Park in Northern California.

“A tree is a tree,” the Gipper was quoted as saying in the Sacramento Bee. “How many more do you need to look at?”

The albino redwood proves that sometimes trees aren’t trees. And like any apparition, you may have to see them to believe them.

Seeing the forest for the trees

Among a sea of green leaves and earthy tones, the albino redwood looks synthetic, as if it has no business in the wild, or as though it was placed there as some odd prank.

Its needles are bright white and waxy to the touch, and are distinctively fragile and brittle compared to their evergreen counterparts.

Coast redwoods, Sequoia sempervirens, among the tallest trees on Earth, grow from southern Oregon to Central California, typically within 50 miles from the coastline. They thrive in areas of abundant winter rain and moderate year-round temperatures.

As a species, the massive redwood is known as a rugged survivor. Shallow root systems can extend far more than a hundred feet from its base, intertwining with those of neighboring trees, increasing the giants’ stability during flooding and high winds.

That the coast redwood’s albino counterpart survives at all is something of a mystery. The ghost isn’t actually a tree, but is closer in appearance to a shrub or bush. Severely handicapped by its inability to produce chlorophyll—the pigment that gives plants their green color and allows them to photosynthesize, or obtain energy from light—the albino redwood is a parasite, dependent on a parent tree.

Although it’s far more common in animals, albinism among plants is extremely rare, given that they can’t survive the way normal plants do. Aaron Sims, a rare-plant botanist with the California Native Plant Society in Sacramento, helps draft the organization’s Rare Plant Index. Sims told New Times the albinos can be described as parasitic in nature, feeding off the roots of a normal host redwood.

Interestingly enough, Sims first saw a wild albino redwood—the same one pictured accompanying this article—during his time as a student at Cal Poly. As a teacher’s assistant of now-retired biological sciences professor Dr. David Keil, Sims accompanied botany class field excursions to Big Sur, where the class would identify native plant species.

The “gem” of the trip every year, Sims said, was the part where instructors let students “stumble” upon one of the albinos.

“When we finally found them, it was always a big mystery [to the students] how these plants were even existing if they are absolutely white and can’t feed themselves,” Sims said.

Dr. Matt Ritter is an associate professor in Cal Poly’s Biological Sciences Department, director of the university’s plant conservancy, and chair of the San Luis Obispo Tree Committee. He now leads his students on those same field trips to Los Padres.

“On that field trip, we’ll see hundreds of species, and millions of individuals of those hundreds of species,” Ritter told New Times. “But the albino redwood, it’s a one-of-a-kind thing. They are extremely rare.”

Ritter said redwoods are relatively special among conifers because they’ve evolved a way of recovering after floods, with the ability to branch out underground. Every now and then, one of those branches comes out an albino.

“Why that mutation happens is completely random,” Ritter said.

While specific causes for the mutation are still being researched, Ritter said the redwood cells don’t split properly. The chloroplast, a sub-cellular compartment typically containing chlorophyll, where photosynthesis would usually occur, either never develops as it would in a normal plant cell, or the chlorophyll never develops inside the chloroplast.

The complex genetics of the coast redwood and the reasons for mutations are currently the subjects of research being done at Stanford University and at UC Santa Cruz. Genetically, the tree is a hexaploid, meaning each of its cells contains six sets of chromosomes, for 66 chromosomes total. Humans, on the other hand, are diploid, with 23 chromosomes. The unique redwood abundance of chromosomes suggests there may be more opportunities for mutations in their genetic makeup. The jury’s still out on that, however.

What is known is that to survive, the albino sucks sugars from its parent tree, though the term “parasite” may not perfectly describe the albino redwood, as it’s not its own individual plant. It’s actually part of the parent redwood to which it’s attached, and therefore, Ritter said, is essentially a parasite onto itself.

[image-3]

“It’s the same individual,” Ritter said. “Plants are strange in that way, that they make these branches and the branches can look slightly different, but it’s just a branch.”

It’s this parasitic nature that gives the albino redwood its other nickname, the “Vampire Redwood.” Aside from its pale shade, the albino redwood’s feeding habits also affect its appearance and feel, such as its needles’ tendency to droop due to lack of fiber and water pressure, as well as its slow growth rate.

Another characteristic that plays into its “ghost” description is the albino’s tendency to vanish in harsh conditions, and reappear at the same spot in following years. In times of flooding or drought, for example, a parent tree may cut off the albino branches’ sugar supply. This may cause the albino to “die” above ground, but in reality it only dies back to the bud of the parent tree. In better times, the albino can grow back.

“They’re freaks,” Ritter said. “They’re just bizarre and weird and amazing all at the same time.”

Ghost hunting

Despite the tight lips, finding an albino redwood isn’t too difficult. There are a number of well-publicized locations, including one in Big Sur.

The Fernwood Resort, near the Big Sur Library, is proud home to the largest known albino redwood in Monterey County. Just behind the pay booth at the main entrance, a massive, 10-foot-tall and 15-foot-in-diameter, frosty white albino greets the visitors.

Diana Valentine, the general manager of the resort, told New Times that the ghost has been there since before the property was developed in the 1930s.

“Ours is well over 10 feet tall, and people seem to find out about it on the Internet,” Valentine said. “People come up and touch it, some will hide messages in it, but as far as I know, no one has ever done anything to hurt it.”

Besides the Fernwood and Los Padres albinos, there are a few other well-known places to find these rare specimens farther north.

According to Sandy Lydon, a Central Coast historian who co-authored a book on redwoods, the majority of known albinos are found in Humboldt County in Northern California, but about a dozen are known to grow in Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park in Santa Cruz County, as well. There are other known ghosts that grow on private property throughout Monterey and Santa Cruz counties.

According to Cal Poly professor Ritter, a number of albinos also grow in Swanton Pacific Ranch, a roughly 3,000-acre property owned by Cal Poly north of Davenport.

The earliest reports of a white redwood date back to the 1860s. In the early 20th Century, late U.C. Berkeley professor Emanuel Fritz equated stumbling upon such a plant to striking gold.

It’s also said that the albino redwood played a role in cultural and religious practices of some local Native American peoples. While a number of tribal representatives didn’t return requests for information for this article, one story was published by travel author Bernyce Barlow in her 2002 book, Sacred Sites of the West.

The legend, as retold by Berlow, dates back about 400 years and tells the tale of Monaca, an Esselen girl who ventured far from her home while picking berries. In her small village was a large white redwood that would glow during the harvest moon. The glow could be seen from the heavens.

Lost in the woods, with the moon as her only light, Monaca was able to find her way back to her family by climbing a ridge and catching sight of the glowing albino.

Barlow couldn’t be reached for the origins of that story.

Historian Lydon told New Times it’s highly possible there are more of these trees in the wild than we will ever know.

“I don’t want to say they are common,” Lydon said, “but I will say they are probably more common than the recordings suggest.”

“Pretty much these are fishing stories,” Ritter said of the rough population estimate. “Because until someone actually does a real survey of them, all we have is what we know of.”

See for yourself

For a publication that holds the freedom of information close to heart, the decision to withhold the precise location of the ghost tree known nearest to SLO County wasn’t taken lightly by New Times.

But for obvious reasons, including the rarity and fragility of the specimens mixed with the temptation for some yahoo to break off a souvenir, State Parks rangers asked us not to give away directions.

According to Patrick Bailey, U.S. Forest Service wilderness manager for the Los Padres National Forest, disclosing the precise location of the wild albino could cause stress on a relatively fragile spot and make it harder for rangers to protect the plant.

“We have had similar situations with overcrowding in certain areas because of something interesting that is found there,” Bailey said.

Despite the request, Bailey said the location of the wild albino is somewhat of a loosely kept secret among locals and rangers. If you ask nicely, someone may point you in the right direction.

Should you come in contact with one, don’t be a jerk and break off branches for a keepsake. It will turn brown after it dies, anyway. Also, please be discreet. The more foot traffic a location gets, the more formalized trails can become—what Bailey calls “social trail-building.”

“In the big picture, it’s all our jobs to protect this landscape,” Bailey added. “But that said, it’s everyone’s forest.” ∆

Contact Staff Writer Matt Fountain at [email protected] and Staff Photographer Steve E. Miller at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023 -

Cal Poly report highlights offshore wind's potential to spur green energy transition

Jun 8, 2023