Fed up: October's partial federal government shutdown is just the latest manifestation of the cyclical crises plaguing SLO County and the nation

By Rhys Heyden[

{

"name": "Promo Temp Targeted",

"id": "PromoTempTargeted",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "4",

"component": "15511697",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "0"

},

{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250 - Inline Content",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "15582119",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250 - Inline Content",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "15582122",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle 9 - 300x250 - Inline Content",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "15582121",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

In Monty Python’s 1979 classic Life of Brian, a group of rebellious, oppressed peasants gathers in secret in order to plan an overthrow of the Roman Empire, which they blame for all of their woes.

“What have the Romans ever done for us?” asks John Cleese’s ringleader, his voice dripping with disdain.

“The aqueduct?” one peasant tentatively ventures.

“Oh, yeah, yeah, they did give us that,” Cleese admits.

“Sanitation?” chips in another peasant.

Everyone admits the Romans did that, too. And the exceptions keep streaming in: the roads, irrigation, medicine, education, wine, public baths, keeping order, bringing peace.

Before long, Cleese’s character is a flustered wreck, and his righteous outrage seems a little silly. The Romans, for all their faults, were responsible for quite a bit.

Equating the contemporary United States to the ancient Roman Empire would be something of a historical fallacy. For one, togas are few and far between nowadays. Also, very few Americans want to bring down our federal government as did those apocryphal peasants of yore.

That said, at midnight on Sept. 30, our federal government did indeed shut down.

Ever since, stakeholders and citizens across the county worked to figure out how the shutdown would truly impact their lives.

What happens next? Who is essential, and who isn’t? Will we still get our money? What’s been closed? What exactly did the government ever do for us?

An important question many more people (including we at New Times) asked was this: Again?

“Crisis fatigue”—along with the crises themselves—is a very real problem for citizens bombarded with a seemingly never-ending cycle of catastrophes: the fiscal cliff, the sequester, the shutdown(s), and the debt ceiling, each one more apocalyptic and inscrutable than the last.

While reporting, we had to contend with unpredictable and sometimes radical shifts regarding the partial federal government shutdown. Late on the afternoon of Oct. 16, Congress appeared to be headed toward a last-second, stopgap deal that will fund the government through Jan. 15 and raise the debt ceiling through Feb. 7.

Though the measure may end the most recent crisis, it sets Congress up for yet another fiscal squabble in the immediate future. The measure also does little to dissipate the smothering cloud of instability that has covered Washington recently, frustrating the nation and SLO County dwellers alike.

Much like the peasants in Life of Brian, stakeholders and citizens say we’re stuck with a frustrating, unstable central government that is nonetheless completely essential to our existence.

Washington problems are SLO County problems

As we entered the third week of the 18th government shutdown since 1976, SLO County was definitely feeling the ripples emanating from Washington’s latest, biggest belly flop. Local government employees were furloughed, streams of money had dried up, and prominent offices and natural sites were shuttered.

Seeking an explanation of the partial federal government shutdown, New Times participated in an Oct. 3 conference call with Congresswoman Lois Capps (D-Calif.), along with roughly a dozen other journalists. Capps represents California’s 24th District in the House of Representatives, which covers all of SLO and Santa Barbara counties, along with part of Ventura County.

As Capps tells it, blame for the shutdown starts and ends with Tea Party Republicans in the House of Representatives.

“This is one faction, in one party, in one house, who have decided they don’t like one law,” Capps told New Times. “They have made a very misguided decision, and we are seeing real impacts right here at home on the Central Coast.”

The law in question is the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—legislation passed in March 2010 that aims to increase the quality and affordability of health insurance. A significant contingent of Republicans demanded the ACA’s repeal or defunding, and refused to pass a “continuing appropriations” act to fund the government in late September without also axing the ACA.

When neither side blinked during back-and-forth approving and rejecting of competing government funding measures, compromise was thrown out the window, and the federal government went into its first shutdown since 1996.

As a result of the shuttering, approximately 800,000 “nonessential” federal employees were immediately furloughed without pay, and another roughly 1.3 million “essential” workers were required to continue working, with their paychecks also in limbo. Though the impacts have been substantial, the shutdown is officially considered “partial” since many “essential” branches of the government have remained quite functional.

Speaking on the third day of the shutdown, Capps said she was committed to reopening the government as soon as possible—and hoping that some of her Republican colleagues would “come back to their senses.”

“People don’t realize how partisan things have become in D.C.,” Capps said. “I think this shutdown sets a terrible precedent because nobody wins in a shutdown, and there are a lot of innocent people who suffer a great deal.”

To prove her point, Capps introduced Michael Cohen, owner of Santa Barbara Adventure Co. Cohen said he was losing about $2,000 per day and has had to lay off some employees because much of his business is based on leading tours of the shuttered Channel Islands National Park.

Capps said Cohen’s plight is representative of a major consequence of the shutdown—namely, citizens losing faith in their federal government. When combined with the constantly renewing threat of the debt ceiling, the current budget sequester, and last year’s “fiscal cliff” panic, the government’s fiscal climate has become increasingly noxious and unstable, she said.

“It’s not that businesses and citizens aren’t ready to thrive and move forward, but this unstable federal government is a tremendous burden to all of us,” Capps said. “I want us to be a reliable partner, but we aren’t one.”

Capps said people want certainty that the government will continue to function, but the series of cyclical crises “cripple” that reliability.

“You can tell I feel very strongly about this,” Capps concluded. “Jumping from crisis to crisis isn’t a good way to govern.”

First effects

In SLO County, Oct. 1 wasn’t exactly the doomsday that played out almost 3,000 miles away in the nation’s capital. Federal government employees didn’t jam the streets, and many residents went about their business as usual.

Behind the scenes, however, it was a hectic and unpleasant day for the county’s federal employees, offices, and territories.

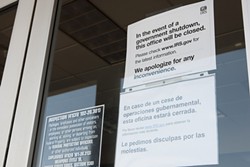

On the office side, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s office in Templeton, the Natural Resources Conservation Service office in Morro Bay, and the Internal Revenue Service office in Santa Maria were hastily closed until further notice.

Out in nature, the entire Los Padres National Forest and Carrizo Plain National Monument were shut down, the Coastal Discovery Center at San Simeon Bay was closed, and tours at the Piedras Blancas Light Station were canceled.

At the county’s two military bases—Camp Roberts and Camp San Luis Obispo—a smattering of maintenance and administrative personnel, largely civilians, was placed on furlough.

Capt. Will Martin, a public affairs officer for the California National Guard based in Sacramento, said the guard experienced around 2,000 furloughs statewide (roughly one third of their full-time force) for about half a week.

U.S. Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel recalled the furloughed military employees starting on Oct. 7, and Martin said the California National Guard is now back at full force, though many remain un-compensated.

Roughly 200 out of 475 employees at Los Padres National Forest were furloughed. A furloughed forest employee, who spoke to New Times anonymously, said workers didn’t want to leave their jobs, but dutifully placed closed signs in the windows and turned off the lights on Oct. 1.

Calls to closed offices and parks were answered by automated messages announcing the shutdown. Many federal government websites either shut down entirely or displayed a “funding lapse” advisement.

“We still have quite a few people wondering when their next paycheck will come, and that is problematic if you’re living paycheck to paycheck,” Martin said. “This kind of action renders us ineffective.”

Personal effects

Even for some SLO County residents who have very little connection to the federal government, the shuttering had a tangible impact.

Lacey and Danielle McNamara, who were married after a two-year engagement on Oct. 12, had been planning and budgeting for their honeymoon trip for more than two years.

They aimed to visit a variety of famous western national parks.

“We heard the news on Oct. 1, saw the pictures of closed gates with the signs and the rangers saying ‘you can’t come in,’ and we said, ‘crap!’” Lacey said.

The couple had planned on visiting Grand Canyon National Park, Canyonlands National Park, and Yosemite National Park, among several others. With only a few weeks’ notice, they had to completely shift their plans to see only state parks, find new campgrounds, and take a different route.

“We’ve been saving and budgeting for this honeymoon for a while now, and it’s frustrating that the government can’t get organized and establish a budget themselves,” Lacey said.

Lacey likened the failed budget negotiations to a marriage: Both parties have to get along and make an effort if they want it to work.

“You kind of rely on your government to take care of your country, and it just seems like everyone has become closed-minded and not willing to try or compromise,” Lacey said. “It’s very frustrating.”

Up in Paso Robles, Christopher Austin is the branch manager at the local office of Primary Residential Mortgage, Inc., a Salt Lake City-based national residential mortgage banker.

Austin said the mortgage lending business has been recovering quite well in Paso Robles—and nationally—since the 2008 crash, but the shutdown put major kinks in the plans of would-be lenders and borrowers.

Essentially, as Austin explained it, all mortgage loans have to be separately verified by the IRS and the Social Security Administration for security and fraud-protection reasons. With both those agencies experiencing heavy furloughs during the shutdown, remaining staff are unable to process new mortgage applications.

“We are getting all of our mortgages as far as we can in the system without those verification steps,” Austin said in early October. “We can go through various processes for about three weeks, but the backlog starts to pile up, and, after three weeks, it will be a real problem.”

Austin said that his branch was sweating it out, but would-be homeowners working through a USDA loan were even worse off, as that part of the agency ground to a complete standstill.

“It’s mostly low-income housing for more rural areas, and if that’s your situation right now, your deal isn’t going to happen,” Austin said. “I can count on two hands the number of people I know in rural North County who have been affected by that.”

He added that the vast majority of money in the mortgage business these days is government-sponsored, with private capital scarce since the government “wiped out” private shareholders in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis.

Austin also echoed Capps’ sentiments: The federal government is unavoidable, ubiquitous, and important, but its fiscal unreliability has increasingly made it a poor business partner and a significant burden.

“People need to have a lot more confidence before they plunge back in,” Austin said. “It’s bad—I wish this government shutdown had never happened.”

Effects on local government

In SLO County, wise saving strategies, a good amount of independence, and fortuitous timing largely shielded local government departments and officials from the worst effects of the federal shutdown.

According to Assistant County Administrative Officer Guy Savage, the county’s biggest headache was the massive Los Osos Sewer project.

According to Savage, $87 million of the roughly $173 million project is provided through the USDA, and all funds have come from the agency thus far, with other funding sources not scheduled to kick in until early 2014.

“We spent $7.8 million on the Los Osos Sewer project in September, but there’s no one working at the USDA right now to process our reimbursement,” Will Clemens, a department administrator at the SLO County Department of Public Works, said on Oct. 10. “We’re waiting.”

Clemens said the county had effectively banked $6 million in prepaid assessments from property owners for the project, but burned through all of that (plus $1.8 million in county cash reserves) while waiting on the USDA for reimbursement. The project is estimated to rack up another $4 million in costs during October.

“We have to ride with the ups and downs for now, but we will definitely keep problems like this shutdown in the back of our minds in the future,” he added.

Beyond the sewer project, Savage said county ties to federal government funding generally follow the same rule: They are tenuous, but fine, for now, and would be problematic if the shutdown were to stretch on for much longer. Though the hopes were that a federal standoff would end quickly, nothing could be taken for granted. Such is the lack of faith in forward motion, worried sights were set far in the future.

“We think we can maintain this stability until early November, and maybe as late as Thanksgiving,” Savage said. “We will have large shortfalls at that point if the government remains shut down.”

Savage said that SLO County draw-downs from the federal government are essentially either quarterly or monthly. The quarterly programs were safe until December, but the monthly ones were only funded through October.

During an Oct. 8 presentation to the county Board of Supervisors, Savage read off a list of county programs that were potentially in danger.

Among them: the Los Osos Sewer project; food vouchers for the Women, Infants and Children program ($300,000/month); the District Attorney’s Victim/Witness Assistance Program; and the Veterans Affairs Work Study program.

As the shutdown stretched on, James P. Erb—the county auditor, controller, treasurer, and tax collector—said the county had sufficient reserves to sustain all of those programs for the next few weeks, but not much longer.

“I’m really hoping to not have to dig into the reserves,” Erb said. “We like to invest in things that we aren’t going to lose money on, but this has got to scare everybody—when we get indecisive events and when it seems like our government can’t move forward.

“It’s really unfortunate that this is happening,” he added.

Savage said that the general theme of the shutdown in SLO County was that consequences are “little things for now” but will become big things after a while of continuing down the same path.

“Political polarization is troubling for all of us, and that’s driving all of this, but there’s only so much we can do here in SLO about that,” Savage said.

Savage, Erb, and Clemens all emphasized the importance and sagaciousness of the county’s well-stocked fiscal reserves. Such reserves can be hard to maintain during economic downturns, but are crucial for providing local stability when the country’s federal apparatus is shaky.

The future

This story went to press on the afternoon of Oct. 16, and the shutdown was still in effect at that point, despite frenzied back-and-forth attempts in Washington to bring it to a close (and avert a further debt ceiling crisis due to commence on Oct. 17).

In an Oct. 15 press release, Congresswoman Capps again lambasted her Republican colleagues, this time for their brinksmanship on the debt-ceiling crisis.

“In the midst of a government shutdown that is hurting real people and damaging our economic recovery, the Tea Party faction in the House should not be allowed to continue using the threat of economic chaos to play political games with the full faith and credit of the United States,” Capps said.

On the larger scale, an Oct. 15 report prepared by Macroeconomic Advisers, LLC—an independent research firm—found that “heightened fiscal uncertainty” has empirically “slowed the annualized rate of growth in the nation’s Gross Domestic Product by as much as 1 percentage point since 2010.”

As the partial federal government shutdown stretched into its third week, SLO County citizens and stakeholders said they hoped for a swift conclusion to the most recent crisis, and have also grown weary of responding and adjusting to the nearly perpetual tension of looming disaster.

SLO County officials said they’re taking measures into their own hands as much as possible.

“If we’re going to have these large swings and instability in funding from the federal government, the prudent financial move would be to build up our reserves,” Savage said. “We need to make sure we’re backed up here, and we’re doing that right now.”

Not to spoil Life of Brian, but Rome was not destroyed by a small group of dissident peasants.

That empire, for all its tremendous accomplishments, crumbled when it overreached, and succumbed to internal political and economic instability.

Staff Writer Rhys Heyden can be reached at [email protected].

Name that crisis!

New Times breaks down the meaning behind some of the most common buzzwords for Washington’s cyclical crises.

Debt Ceiling: The U.S. has yet to breach this ceiling or limit, at which point it would be unable to pay its debts. In 1917, legislative policy first created limits to the amount of debt the U.S. Treasury can create. Though it was originally supposed to be a formality, House Republicans (in 1995, 2011, and, now, 2013) have held back their approval of debt increases in order to create leverage for their desired budgetary agendas. Many have criticized this tactic, as Congress has already approved the legislation that would elevate the debt ceiling in all of these cases. It has also become common practice to set very short-term debt limits, which has increased the frequency of debt ceiling standoffs. The U.S. Treasury’s current borrowing limit will be reached on Oct. 17.

Fiscal Cliff: A projected double-whammy of a simultaneous tax increase and spending decrease that was supposed to torpedo our economy starting in January 2013. After much (largely justifiable) concern from the media and lawmakers, the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 intervened at the last minute and took the oomph out of the fiscal cliff crisis. This was largely accomplished by an extension of the Bush-era tax cuts, stabilizing our deficit—at least for now.

Sequester: Approximately $85.4 billion in draconian annual spending cuts automatically triggered by Congress’ failure to agree on a budget. These sequester cuts were scheduled to start on the first day of 2013, but were delayed two months in a futile, last-ditch attempt to reach an agreement. They went into effect on March 1 of this year, and are ongoing. Many have criticized the sequester cuts for being blunt and economically harmful.

Government Shutdown: We’ve had 18 of these since the first one in 1976, and the most recent one began at midnight on Sept. 30. This kind of shutdown is triggered when Congress fails to approve a “continuing appropriations” act to fund the federal government. It’s officially considered a “partial” shutdown since “essential” federal government operations continue, but its effects are nonetheless manifold. The previous shutdown in 1995-’96 lasted for 21 days, a record high.

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023 -

Cal Poly report highlights offshore wind's potential to spur green energy transition

Jun 8, 2023