A chance at life: Modern blood thinners like Eliquis are becoming increasingly popular for their safety and effectiveness, but the death of a former Cal Poly professor brings light to lesser known risks

By Kasey Bubnash[

{

"name": "Promo Temp Targeted",

"id": "PromoTempTargeted",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "4",

"component": "15511697",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "0"

},

{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

The day Philip Ruggles died, he was the picture of health. Until, suddenly, he wasn't.

Nearly 34 years of teaching sales, estimating, marketing, and pricing in Cal Poly's graphic communication department left Philip with a propensity for organization and a keen eye for detail. In the classroom, he was pragmatic, voraciously curious, and boundlessly devoted to his students. He approached his own health the same way.

Phil stayed fit through a healthy diet and consistent exercise. He monitored his blood pressure and never missed a day's dose of medication or a checkup with his doctor. He took care of himself, so it was all the more shocking to his family when everything so quickly unravelled on Oct. 19, 2019.

According to Phil's wife, Joanne Ruggles, that day started off much like any other.

Phil woke up early and went for a ride on his bicycle. He took the family dog—still just a puppy—to a training class and sent silly photos of the dog playing to his daughter. Once Phil returned home, he made lunch for himself and Joanne—he was often the one in charge of prepping breakfast and lunch—and after that, he did some work in his office, then briefly laid down for a little rest, and went out and ran a few errands later in the afternoon.

It was about 4 p.m. when Phil got back home and only minutes later that he called his wife into the kitchen and said, "Joanne, I think I'm having a heart attack."

Joanne called 911 and almost immediately an emergency fire crew was at their Patricia Drive home, a somewhat secluded and modern house nestled against the northeastern face of Bishop Peak. Soon Philip was strapped into an ambulance and on his way to French Hospital Medical Center, where first responders said he would receive the most specialized cardiac care the Central Coast has to offer.

When Joanne made it to French Hospital, she said she was led to a room where Phil was hooked up to all kinds of machines and tubes and awaiting a CT scan, which she was told would determine whether he'd really had a heart attack. Phil was totally cognizant and told Joanne about the pain he felt in his back and running down the side of his neck, symptoms that seemed to align with what Joanne knew about heart attacks.

But when Phil's doctors came back with the CT scan, their moods had shifted. Everything started to feel a lot more serious. As a cardiologist looked over Phil's records, Joanne asked if her husband had had a heart attack. The doctor told Joanne that he only wished that were the case.

The doctor explained to Joanne that Phil had experienced an aortic dissection, a rare and often deadly event in which the innermost layer of the aorta tears, allowing blood to surge through the wound and causing the inner and middle layers of the aorta to separate. Treatment typically requires emergency surgery.

Joanne was initially most concerned about the surgery, but then the true gravity of Phil's situation became even clearer. When the doctor asked if Phil was on a blood thinner, and Phil confirmed that he was on Eliquis, a new-era direct oral anticoagulant used to prevent blood clots, Joanne said the doctor's face dropped. He shook his head.

"We can't do surgery," Joanne remembers the doctor saying. "We can't do surgery for 48 hours with someone who's on Eliquis."

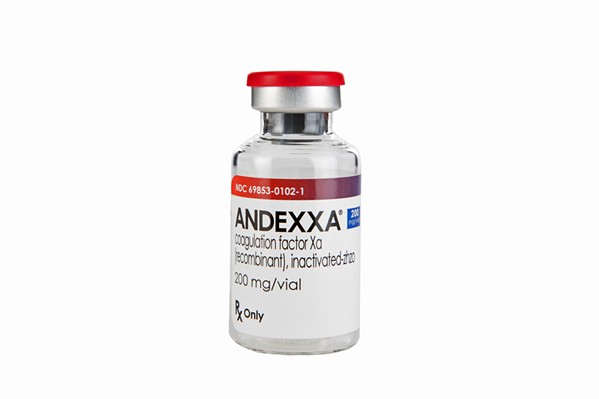

Eliquis and blood thinners like it, Joanne said she was told, stay in the body for about that long, and if a person were to go into surgery while using a blood thinner, he or she would bleed out on the table. There is an antidote, Andexxa, that almost instantly reverses the effects of Eliquis. But when Joanne assured the doctor that her insurance would cover the cost of the antidote, he told her French Hospital doesn't keep it on-site. It's too expensive, she said the doctor told her, and has too short a shelf life to be worth the investment.

Joanne later discovered that Phil's situation wasn't all that unique. Eliquis and other blood thinners like it—factor Xa inhibitors—hit the market in the early 2010s and offer what's largely considered a more effective and convenient alternative to warfarin, a decades-old anticoagulant that often causes serious side effects and requires close monitoring. Factor Xa inhibitors are widely popular and, according to Portola Pharmaceuticals, the company that markets Andexxa, more than 5 million patients are estimated to be prescribed them in the U.S. alone.

But this new generation of blood thinners comes with a caveat: While the effects of warfarin can be easily reversed with a shot of vitamin K in the event of major bleeding, factor Xa reversal is more complex. Andexxa, andexanet alfa, is the only antidote approved to reverse bleeding in people taking Eliquis, and while Andexxa is widely available in densely populated areas of the U.S., its price tag and expiration date have kept it off hospitals' shelves in regions like the Central Coast.

According to Portola Pharmaceuticals, only about 3 percent of U.S. patients who were hospitalized because of bleeding related to factor Xa inhibitors in the last year were treated with Andexxa.

That's left people like the Ruggles family with limited options in emergency situations.

"I don't know whether Phil would have been helped by this antidote," Joanne told New Times about a month after his death. "So I'm not saying that he would have lived or how he would have lived if this antidote was available. But if it was your loved one lying in the emergency room, bleeding internally, wouldn't you want every option that you could have?"

Unanswered questions

Phil didn't survive his aortic dissection. Shortly after his doctors discovered the need for Andexxa, they scheduled Phil for a transfer to USC Medical Center in Los Angeles, where doctors said the antidote would be readily available.

Because of the aortic dissection, Phil was bleeding internally for hours while all these decisions were being made. Joanne said he was loaded onto a helicopter sometime around 9 p.m., but he died of complications associated with internal bleeding while in flight.

Joanne and her daughter, Lauren Donovan, were both devastated. They agreed that they had to do something to shine a light on this blood thinner issue, to effect change, but they didn't initially agree on how to get there. Joanne, a painter who spent nearly 30 years teaching in the art department at Cal Poly, wanted to donate a few doses of Andexxa to French Hospital in Phil's honor. Lauren, an attorney in Southern California, wanted to sue French for negligence.

But in such a lawsuit, the blame wouldn't fall solely on French Hospital or the nonprofit health care system that runs it, Dignity Health. The individual doctors, who Joanne and Lauren truly believe did the best they could to help Phil, would likely face repercussions.

Lauren and Joanne don't want to see that happen. They just want to prevent similar situations from occurring in the future.

Despite multiple requests for comment, Dignity Health refused to discuss this story or to confirm whether it carries Andexxa or any similar drugs. But Joanne said she knows what the doctors told her that night, and she's confident that what happened to Phil is a problem that needs addressing.

It's too late for Phil, she said, but not for others who might be put in the same position.

"If Phil's death and us being public about this creates some kind of a solution that gives this option for people in our region," Joanne told New Times, "then we accomplished something. Then his death had, I don't want to say purpose, but it accomplished something good."

A new era

People all over the world have been taking blood thinners for decades to prevent the formation of dangerous blood clots that can lead to a number of issues, including deep-vein thrombosis and stroke.

For years, people at risk of developing blood clots essentially only had warfarin, an anticoagulant that works by blocking the production of substances in the blood called clotting factors. While warfarin targets several clotting factors, the newer anticoagulants target only one: factor Xa.

Warfarin is cheap, but it's difficult to manage. Patients using warfarin are required to maintain strict diets and need regular blood tests, and warfarin tends to trigger severe internal bleeding, oftentimes in the brain.

So when factor Xa inhibitors—brand names Eliquis, Bevyxxa, Pradaxa, Savaysa, and Xarelto—hit the market, people jumped at the chance to prevent blood clots in a more effective and safer way. Factor Xa inhibitors require less monitoring, and although they too can trigger internal bleeding, the chances of bleeding in and around the brain are about 50 percent lower, according to a 2018 article published by Harvard Medical School.

The catch?

"Being on these blood thinners is a high risk affair if anything happens," according to Dr. Fernando Fleischman, co-director of the Comprehensive Aortic Center at Keck Medicine of USC.

"Anything," as in any accident or medical event—from a car crash to a hemorrhage—that could cause a person to seriously bleed.

Blood thinners work by preventing blood from clotting. That's great if you want to avoid having a stroke, Fleischman said, but it's bad if you experience a major bleeding event or need to go into emergency surgery. If blood isn't clotting in a wound, it'll just keep gushing.

The same bleeding risks come with warfarin, but its effects can be reversed quickly and easily with a dose of vitamin K, which is readily available at hospitals pretty much everywhere. While some hospitals use Kcentra, a prothrombin complex concentrate, to reverse the effects of factor Xa inhibitors, it's not always effective, and, according to Harvard Medical School, there's only one Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved antidote to the effects of factor Xa inhibitors Eliquis and Xarelto, and that's Andexxa.

A single dose of Andexxa costs $24,000, according to Portola Pharmaceuticals—and that's just the low dose. The high dosage is double the drug and double the price.

For major and specialty hospitals in highly populated areas, Fleischman said it makes sense fiscally to carry a drug like Andexxa. Medical centers like USC perform so many surgical operations and treat so many patients that he said it would be inappropriate not to.

But in general, Fleischman said Andexxa is rarely needed. So for hospitals outside major cities, he said it would be "foolhardy" to try to scrape together enough money to purchase a drug that would only be left to expire a majority of the time.

Still, he said, situations like Phil's are problematic. Fleischman firmly believes the decision to transfer Phil to LA likely had less to do with Andexxa and more to do with his aortic dissection, a typically fatal event that requires complex treatment and top surgeons. Despite that, Fleischman said he's not sure patients know enough about the risks associated with taking newer blood thinners like Eliquis and Xarelto.

Sure, the labels include warnings, and most doctors tell their patients about the less than pleasant possibilities associated with the drugs. But Fleischman said he's not convinced there's been enough research into what poses the bigger threat: blood clots while not taking a factor Xa inhibiting blood thinner, or the inability to stop a bleed while on one.

A problematic solution

Before Andexxa was approved by the FDA in 2018, there was no other antidote approved to stop bleeding associated with Xarelto and Eliquis, similar blood thinners that received FDA approval in 2011 and 2012, respectively.

That's according to Dr. Jeff Myers, interim chief medical officer and vice president of medical affairs at Portola Pharmaceuticals.

Xarelto and Eliquis became popular fast, Myers said, adding that roughly 4.4 million Americans and 300,000 Californians are prescribed one of those two anticoagulants.

The lack of a proven antidote became a widespread issue almost as quickly.

When Andexxa was first being developed, it was pushed through the FDA's accelerated approval pathway, a program that was launched in 1992 to allow for faster approval of drugs that could help fill critically unmet medical needs. Following Andexxa's approval, Myers said nearly 20 medical societies, which create guidelines for best medical practices, analyzed the drug and concluded that Andexxa should be used as the preferred antidote to Xarelto and Eliquis over prothrombin complex concentrates like Kcentra.

"So you end up with this pathway where the FDA has said, 'This is an unmet medical need,' the medical societies have said, 'This is the drug that you should be giving to reverse this,' and yet you have hospitals that, even in the face of that pathway, have chosen not to put [Andexxa] on formulary," Myers told New Times. "And that's the thing that we are still having a little trouble understanding as a company."

Andexxa's steep price is the No. 1 reason hospitals object to Andexxa, Myers said. Myers admitted that drugs like Kcentra are much cheaper than Andexxa, but he said they aren't approved by the FDA specifically for the reversal of Eliquis and Xarelto, and they aren't proven to be as effective.

Andexxa's $24,000 a dose cost is, for the time being, unavoidable, because of its complex and costly manufacturing process.

The drug, which is administered via injection, is made using Chinese hamster ovary cells, according to Myers, and can only be produced in small batches. Researchers are always working to develop ways to create bigger yields and less intensive and costly methods of producing the drug, but until then, the price is what it is.

Portola does, however, allow distributors to provide Andexxa to hospitals on consignment, which enables facilities to stock up on Andexxa without paying for it until it's administered to a patient. Even if the drug expires while at a hospital—Myers said more recent batches of Andexxa have a shelf life of 32 months—the product can be returned for full credit.

"So we tried to make it so that it's highly accessible for all hospitals and institutions," Myers told New Times.

He said he's always surprised when facilities choose not to carry Andexxa, especially considering that bleeding events associated with Eliquis and Xarelto aren't becoming any less prevalent.

Portola estimates that there are about 150,000 hospital admissions a year attributable to bleeding related to factor Xa inhibitors across the U.S., and within the last year, Myers said only about 4,000 of those patients were treated with Andexxa.

In March 2019, Johnson and Johnson and Bayer, the companies that jointly sell Xarelto, agreed to pay $775 million to settle about 25,000 state and federal lawsuits filed by patients who claimed they weren't adequately warned about bleeding risks associated with the anticoagulant. Although neither company admitted liability, they said in a joint press release that "even while winning in court, complex litigation demands an enormous amount of time and resources."

The Joint Commission, a nonprofit that develops best health care practices and accredits hospitals across the nation, addressed the potential bleeding risks associated with the new generation of blood thinners in December 2018. Because of what it called "a rise in adverse drug events associated with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs)," including Eliquis and Xarelto, the organization added eight new patient safety requirements that all accredited facilities now have to adhere to when prescribing anticoagulants.

These issues were highlighted again in a July 2019 Joint Commission "Sentinel Event Alert," a publication sent to all Joint Commission-accredited organizations when a high risk medical situation is identified.

In the July 2019 alert, the Joint Commission recommended potential strategies for managing the adverse bleeding effects of anticoagulants, which the alert said "have been named second of the top 10 medications involved in error incidents causing death or serious harm."

"Unlike the more widely available reversal agents for warfarin and heparin, reversal agents for DOACs are lesser known and may not be available in every setting," the alert reads. "Also, some DOACs have no FDA-approved reversal agent at this time. Therefore, bleeding complications can be severe if these patients are not assessed according to the guidelines on the management of DOACs."

In the alert, the Joint Commission points out that a reversal mechanism that works for one blood thinner may not work for another, and suggests that hospitals stock antidotes appropriate for each existing anticoagulant. The Joint Commission also says information regarding the risks associated with drugs like Eliquis and Xarelto should be fully discussed with patients and their families and caregivers.

That didn't happen in Philip Ruggles' case.

Because Dignity Health refused to comment, it's impossible to know what policies French Hospital Medical Center adheres to when dealing with a bleeding issue like Phil's. But French Hospital Medical Center is accredited by the Joint Commission, and according to its most recent quality check, French had implemented the 2019 anticoagulation therapy safety strategies to the Joint Commission's satisfaction.

Although Dignity Health wouldn't confirm whether it carries Andexxa at any of its Central Coast hospitals, Portola has an online "Andexxa locator," that lists every medical facility known to carry Andexxa within a few miles of any location searched. According to the locator, the drug is abundant in LA, San Diego, and the Bay Area. About eight medical centers in LA alone had stocked up on Andexxa as of September 2019, the last time the locator was updated.

The locator lists Santa Barbara Cottage Health Hospital as the only facility on the Central Coast carrying Andexxa. Because patients typically have to be transferred to a hospital with a higher quality of care, it's unlikely anyone living on the Central Coast but outside of the Santa Barbara area would be transferred to Cottage Hospital if in need of Andexxa.

Calling for change

Every day Joanne Ruggles misses her husband. People say it gets easier, but sometimes she wonders whether it really will.

Theirs was a relationship that held true to the old "opposites attract" adage. While Phil's life and job revolved around dollars and cents and creating successful business ventures through smart fiscal decisions, Joanne's centered on self-expression, emotional instinct, and art.

Phil liked to tell his students that the success of a business hinges upon its ability to manufacture a quality product with no variation—the same product every time for every customer. In Joanne's classes, the opposite was true, and students could only be successful if they created pieces that were totally unique and overflowing with originality.

Years ago, a student who ended up taking a class from both Phil and Joanne—a rare phenomenon—playfully asked Joanne, "How do you two live together?"

But that yin and yang connection always worked for them. They had wildly different skill sets and modes of operation, but they adhered to the same core beliefs. They were both born teachers. They both loved kids and helping out in the community and traveling.

"So I think it was a very, very good marriage because we were just in such different fields that we kind of marveled at what the other one did, but had no need to go there and compete with each other," Joanne told New Times. "It was like, you know, you sort of had the whole spectrum covered."

He was her best friend, her support system through a battle with breast cancer and a long fight for gender equality, and her partner throughout so much of her life. During his time here on Earth, Phil always fought for what he thought was right. So that's what Joanne is doing now.

She doesn't blame the doctors who were there that night in October 2019. Many of them knew Phil personally and were more than sad to see him go. She's well aware that Phil's medical situation was rare and severe and that there's a possibility he would have died whether French Hospital carried Andexxa or not.

To her, that doesn't change a thing.

"So would he have died had they had the antidote here? I don't know," Joanne said. "I can't say that. But I sure as hell would have liked to have that chance." Δ

Contact Staff Writer Kasey Bubnash at [email protected].

Do you think the SLO County Board of Supervisors should have gone against their policy that states funding for independent special districts should not result in a net fiscal loss to the county?

Latest in News

Comments (9)

Showing 1-9 of 9

Readers also liked…

-

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023 -

Cal Poly report highlights offshore wind's potential to spur green energy transition

Jun 8, 2023