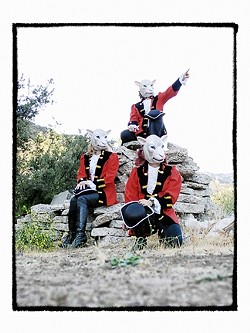

'We aren't who we are'

'Lyrical Play,' artist Wendy Marvel's collaborative photo series featuring women in animal masks, reevaluates environment, identity, vulnerability, and fear

By Anna Weltner[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

Late one night in New Orleans, in what you might loosely call the wrong part of town, three women took a taxi cab to a hurricane-ravaged cemetery dressed as goats. That is, if goats wore white lab coats and gleefully ran about on their hind legs.

These weren’t ritualistic weirdoes, as frightened passersby seemed to think. Under the leering animal masks were photographers Wendy Marvel, Felicia Michaels, and Natalie Gamble, three nice ladies working on an art project.

“We don’t know why we did it,” admitted Marvel, the group’s de facto ringleader. “It was a bad part of town, and we were told we were going to get robbed or mugged or whatever. We were scared running around with these masks, but we realized, we were scaring other people.

“This couple came around when we were shooting, and they were terrified; they thought we were, probably, Satan worshippers or something. They thought we were doing some ritualistic thing. And I said, ‘No, no, we’re just shooting a photo project,’ and they kind of looked like they believed me, but then they ran away.”

The dubious goat-head photoshoot was part of an ongoing collaborative series featuring Marvel, Michaels, and Gamble as masked animal-women cavorting in bizarre and often dangerous locations, the results of which are currently hanging in the Vale Fine Art show “Lyrical Play.”

While in New Orleans, the three women became monkeys dressed in silky underthings in what could easily have been a brothel: staring into a remotely controlled camera, each face eerily frozen in the exact same gaze, the monkey-women appear to fix one another’s brightly colored hairdos. Their gestures call to mind both the womanly camaraderie of a beauty parlor and the monkeyish trait of picking bugs from one another’s hair and eating them—a humorous, and perhaps critical, comparison.

Another shoot saw Marvel, Michaels, and Gamble as foxes trekking through a Louisiana swamp. Machetes in hand, they carve out their own path, and, in the resulting photographs, appear ready to do so the same thing to the viewer’s face. Here, as Marvel and friends discovered in the cemetery, the hunted may become the hunters.

“For those foxes,” Marvel explained, a note of pride in her voice, “we were in a bayou with alligators. And we actually brought a couple of people along with us to kind of keep an eye out, because we were traipsing through this swamp. We were pretty scared. It was raining, and we really did start to feel like we had to act predatory in order to … .”

The artists trailed off, searching for the right words.

“I don’t know; it’s a strange thing. It’s kind of difficult to describe, Anna. I wish that other people could do this, especially other girls that I know, just to get out of their skin and feel a little less vulnerable, and know another side of themselves.”

Looking through the artist’s previous series, one might conclude that Marvel—who grew up in upstate New York and now lives in Santa Monica—has devoted much of her artistic career thus far to the exploration of identity. In 1998, she co-founded Slender Fungus Multimedia, a design company tailored to the needs of the entertainment industry, counting among its clients such illustrious artists as Coldplay, Alanis Morisette, and the Goo Goo Dolls, as well as Microsoft and Intel.

Shortly after college, where she majored in editorial illustration (with a minor in literature), Marvel went on to work as a contractor doing illustrative and design work for companies like Disney, Fisher-Price, and Corning Glass.

After moving to Los Angeles, Marvel started work at a web company, which later sent her to London to open up a new branch. It was there that the artist, perhaps tired of creating others’ identities and curious about her own, began experimenting with self-portraiture.

“When I was over there,” she said, “I just started taking photographs of myself. I was feeling a little bit isolated. And that was a way to deal with the loneliness a little bit … . They always say artists work best from that place of solitude or loneliness. I just started making art. At that time, I was doing photography, just running around the city trying to get to know my way around. I started photographing myself in settings. That’s how I got into art and the gallery scene.”

Marvel, perhaps as a momentary rejection of the entirely digital world in which she spent her working life, also began embracing more traditional media: processing her own photographs and incorporating them in more sculptural pieces made of resin and wax.

“I think I was craving using my hands to do some of this stuff; I wanted to work on something instead of staring at a computer screen,” she said.

Marvel’s interest in tangible objects was furthered when she met her boyfriend of four years, “kinetic sculptor” Mark Arnon Rosen, with whom Marvel made the mechanized flipbooks included in “Lyrical Play.”

Her work with Arnon Rosen also marked the first of many collaborative projects, and included a series of beautiful balsa wood “light sculptures”—illuminated three-dimensional pieces whose physical form, it seems, was only important as a means to manipulate light and dark, projecting intriguing, abstract shapes onto the wall behind them.

Such projects aside, photography and self-portraiture still represented a large part of Marvel’s body of work. The collaborative body of work represented in “Lyrical Play,” the artist admits, stemmed in part from a desire to do something that felt less self-centered.

“All my previous work, that was all me,” she said. “It was always me shooting myself. I never fully understood why I was attached to doing that.”

(To her great relief, however, Marvel’s deeply introspective work appeared to resonate with other young women: “When I was doing that self-portrait stuff, I had a lot of girls … that were coming forward and wanted to make a connection. They wanted to reach out and talk with me. … It made me feel appreciative, or filled with gratitude that what I was doing wasn’t just a self-absorbed project, which it really was, but that someone else was getting something out of it, that girls were trying to connect to something in themselves.”)

But after so much focus on her own identity, working with others was a welcome transition.

“Maybe, after doing my self-portrait work, it was a self-defense kind of thing, where it wasn’t about just me anymore, it was about other people,” Marvel mused.

She met fellow photographers Gamble and Michaels during a trip to the Moroccan city of Fez. When the three women hit it off, Marvel decided she wanted to include them in her continuing artistic exploration of identity. On a whim, Marvel bought burqas for each of them and set up a photo shoot featuring the three of them at a tea ceremony.

“From that point on, they were so excited by the whole experience that they said, ‘Can we do this again?’ and I said yeah. We started going to costume shops together and planning out settings we could go shoot in,” Marvel said.

In the shoots that followed—animal heads, it was decided along the way—the three women decided to follow the tradition they’d established in the Morocco shoot: masks and props would be sourced from the locations in which they were shooting. The choice may lend the images an air of authenticity or belonging, solidifying the idea that the creatures Marvel and friends create are indeed native to their environment.

The women became sheep dressed as soldiers from the Revolutionary War, and rabbits on the inhospitable shore of the Salton Sea. In a gilded, anonymous bedroom, they became pigs in pajamas—though the final images contain none of the silliness that phrase evokes. Instead, they call to mind, with their unnerving combination of masked identity and baroque, velvety interiors, some forgotten scene from Eyes Wide Shut.

“I have to admit, Anna, when I think back on those things, it’s a thrill feeling I get, but it makes me sweat a little bit,” Marvel said. (The artist, I notice, has an uncanny way of making one feel as though a deep secret is being divulged, simply by addressing the listener by name.)

With the exception, she said, of the pig shoot, “Each one of those environments we put ourselves in was really uncomfortable and dangerous, and the adrenaline that was running through us is what draws the shoot. We get to become different creatures, but we also, because we’re in some strange, foreign settings, it makes us feel like we aren’t who we are, we’re not girls, we’re just these new strange creatures.”

The Moroccan shoot may also have set a precedent of dislocation, or, though this may be a charged word, exoticism. Marvel, Gamble, and Michaels are all avid travelers, and planned many of their shoots based on the bizarre—and not always accommodating—places they wanted to visit.

The noxious, strangely beautiful Salton Sea, for instance, stirred the imaginations of Marvel and company, who went out dressed in heavy white bunny suits in what turned out to be 100 degree heat.

“We went to these locations where there were these abandoned buildings and abandoned trailers,” she said. “And I don’t know if you’ve ever been to the Salton Sea, but the smell is horrific. Dead fish and chemicals everywhere. We thought white bunny suits in this really disintegrating environment seemed apropos. I don’t know why! And actually, it worked out really well, Anna, because we felt fully suited up. We rolled around in that stuff.”

It might come as a surprise to learn that Marvel actually hates masks. They really creep her out. But being behind one, she says, is an entirely different experience altogether.

Why, in fact, are masks scary? Beyond the obvious concealing of identity, are masks also frightening because of the ubiquity they make possible? What if everyone wore the same face, sacrificing individual expression—with its potential to invite both scorn and adoration—for the safety of being just like everyone else? What if everyone had no face? That’s disgusting.

What’s unsettling about Marvel’s work, though, are the permanent expressions her creatures wear. Feeling threatened in the face of their unblinking gaze, our human tendency is to try to search their features for signs of anger, fear, compassion, curiosity—anything that might help us divine the intentions of the animal-women in front of us. And yet the faces remain ubiquitous, blank.

It’s impossible, too, to deny the feminist aspect of “Lyrical Play.” The three women in the series seem to acknowledge their status as the more vulnerable of the species, and, from there, turn the idea of vulnerability on its head: Assuming the identities of animals often considered prey, they proceed to perplex and terrify the viewer.

“What we’re addicted to, on this project, I guess it’s a feeling of control, of owning that vulnerability,” Marvel said. “And I do think it is a feminine thing, too. You constantly know that you are vulnerable in some respects. Did I lock the door? Are the windows shut? I’m alone, is that okay? Even when you’re walking to your car—as a woman, I think we walk in this world differently. It is an undercurrent, almost a subconscious level, of fear. There’s always a plan in your head. It’s almost instinctual. You’re thinking, if this happens, what do I do? Or, where do I go? You just do it. It’s automatic.

“But, Anna, it’s interesting: I think they’re more afraid of us than we are of them, even though we think it’s the opposite.”

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023