The long, storied history of San Luis Obispo's historic Chinatown and the artifacts left behind

By Colin Rigley[{

"name": "Newsletter Promo",

"id": "NewsletterPromo",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "4",

"component": "15264767",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "0"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

At the end of Dana Street in San Luis Obispo, there is a white, wooden fence. Behind that fence, there is a white building marked by a bronze-colored placard with the words, “Rosa Butrón de Canet de Simmler ADOBE c. 1845.”

In the back of the Palm Street parking garage, there is a small window display that contains artifacts next to poster boards commemorating the history of the site: the remains of old Chinatown and long-forgotten dormitories in which Native Americans were housed during missionary times.

In the SLO County Library, there is a locked backroom on the second floor marked “Local History Room.” In that room, there is a green hardbound version of Patricia Ochs’ 1966 Cal Poly senior project, “A History of Chinese Labor in San Luis Obispo County and a Comparison of Chinese Relations in the County with the Anti-Chinese Movement in California, 1869-1894.”

Ochs wrote, “Written histories in the past have been incomplete in their portrayal of the populace of San Luis Obispo County. Past histories have acknowledged mainly prominent citizens and have ignored the contributions of diverse groups.”

John Parker is an archaeologist—as well as vice president, project review coordinator, and collections manager—with the Lake County Historical Society. He spent 17 years working with Chinese and other artifacts unearthed before the construction of the Palm Street garage, eventually storing them in the white-fenced adobe, attempting to piece together a history that was largely left out of historical accounts.

On Sept. 18 of this year, Parker wrote in an email to city officials that he believed the city’s handling of those artifacts “has been, and continues to be an abysmal mess of ignorance and stupidity.”

Chinatown lost

Depending on where you look, accounts of the local Chinese population vary. In 1870, The Tribune first noted the arrival of 59 Chinese immigrants, according to Ochs.

Historic Census data for the county shows that the Chinese population rose to 183 in 1880, then to a four-decade peak of 386 in 1890. (At the time, the countywide white population fluctuated from 1,021 in 1860 to 8,783 in 1880.)

But Cal Poly Professor Alice Loh wrote in an online history of SLO’s Chinatown that “because of the joining of the two railroads at this county, San Luis Obispo by 1870 had obtained the biggest settlement of Chinese community in California.”

Dan Krieger, a Cal Poly professor of history and 31-year columnist for The Tribune, said Loh’s assessment is “generally accepted” for periods of heavy construction, as Chinese laborers built wharves at what is now Port San Luis and vital infrastructure for the railroad that runs through SLO along the Cuesta Grade.

“We think there were as many as 3,000 workers,” Krieger said.

The heart of the Chinese community could be found in SLO’s historic Chinatown, which is now mostly parking lots and garages spanning Palm Street between Chorro and Morro. The old Ah Louis store remains, as does a former brick candy store (now a real estate office) and the Mee Heng Low noodle house, which still sits on some of the original wooden foundation.

SLO’s Chinatown is often largely credited to Ah Louis (pronounced “loo-ee,” whose given name was Wong On), who emigrated from a Chinese village at the age of 21. Louis brought hundreds of laborers into the area and served as a liaison between the Chinese and predominantly white communities.

However, anti-Chinese sentiments began to reach a fever pitch in the late ’70s. Unemployed workers and economic depressions led to the rapid scapegoating of Chinese, who were often gainfully employed as manual laborers.

“While the San Luis Obispo Tribune continually expressed its wishes for restriction of Chinese immigration, it never condoned violence against Chinamen already at work in this country,” Ochs wrote. “Any violence committed against the Chinamen by ‘whites’ was severely condemned.”

Statewide, mounting Chinese racism was typified by the rise of the Working Man’s Party, under the slogan “the Chinese must go.”

In SLO County, the Board of Supervisors at one time considered a proposal to issue taxes on inhumed Chinese remains that were kept in local cemeteries before they could be shipped back to China. Chinese laundries thrived in the community, but were vilified and boycotted as an “effective and legal means to ridding the county of that people,” Ochs wrote, quoting an article from the time.

In 1879, a Chinese resident in San Miguel was taken from his home and “accidentally” shot.

Locally, statewide, and nationally, there grew an effort to address the so-called “Chinese question.” In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned immigration of Chinese laborers to the United States. The subsequent Geary Act a few years later required Chinese people in the country to obtain registration certificates.

And further violence ensued.

Chinese laborers in Arroyo Grande were gathered up and told to leave.

“This they proceeded to do, and were taken aboard a hand-car and brought to the horseshoe, this side of Arroyo Grande, when they were unloaded and told to leave, never to return, under pain of hanging,” Ochs wrote, again quoting news accounts.

As racial tension and violence increased, local work evaporated, and new opportunities became available elsewhere, the local Chinese population began to move away.

Still, there remained a core population in the local Chinatown of about 200 to 300 people as late as the 1920s, Krieger said. But during and after World War II, even they had all but vanished, and SLO residents started conjuring new uses for the land and buildings that used to be Chinatown.

In the early 20th Century, Caltrans crews demolished much of an old Chinese cemetery to make way for a new highway, Krieger said.

In the 1940s, SLO officials demolished the Chinatown structures, which—aside from the Ah Louis shop—had reportedly fallen into disrepair and were prone to fire.

City officials soon began eyeing other structures across the street and considered a second garage, which would require the demolition of buildings such as the former Shanghai Low restaurant.

Steve Yung is one of the last local descendants of three original SLO Chinese families. He married into the Gin family in 1969 and moved with his wife from Hong Kong to SLO to work in the restaurant.

Yung, who took over ownership, saved the buildings from planned demolition in the late 1990s, but he later sold due to expensive retrofits required after the 2003 San Simeon earthquake. Yung told New Times that he didn’t feel Chinatown was given the support it needed throughout the years.

“Chinatown is not a Chinatown anymore,” he said.

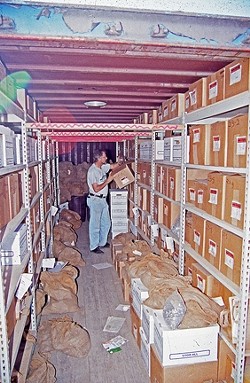

What remains of the historic district is preserved in the artifacts salvaged before the Palm Street garage went up. In 1987, a team of archeologists had about two months to dig out pots, waste pits, animal bones, and other features. And for a decade, the 5 tons of material the crew unearthed sat in a shipping container. The area was declared a historical district in 1995, and Chinese symbols—translated as “love” and “double joy”—were inscribed on the parking garage.

In 1997, Parker was the only bidder for the contract to clean, sort, and catalog the artifacts, he said.

“Basically, it gives you the story of the people that were left out of the history books, and that was one of the main reasons I took on the Chinatown project,” he said.

But in a recent interview with New Times, Parker explained that he now worries he’ll never know what might have been lost.

What remains

When potential bidders first examined the storage container, most estimated it was a $200,000 project, Parker said.

“They opened up the cargo container and we all looked in and, well, just kind of shook our heads.”

The city awarded Parker a $44,966 contract to complete work on the Chinatown artifacts. At the onset of the project, Parker worked with a small team of archaeologists, who trained as many as 150 volunteers within the first year—and that number increased over time. In the early years, they took the container to a vacant poultry lab at Cal Poly and began sorting the material.

The project moved along smoothly for the first few years, even earning a visit from Huell Howser, who featured it on California’s Gold. In fact, much of the recovered material was from the Mission era. Chinatown was built upon old dormitories for Native Americans, Parker said. Archeologists recovered bits of plaster floor that had been stained red with ox blood.

But after about six years, Cal Poly needed the lab back, Parker said. The team also lost its storage container.

Parker said he first asked to store the material with the San Luis Obispo County Archaeological Society, even arranging an agreement that resulted in matching grant funds that allowed the society to upgrade its facility behind Cuesta College.

When he approached a society officer, Parker said the response was “no; I don’t want all those dirty artifacts in here.”

“I said, ‘Excuse me; you are an archeological collection facility and that’s where all those dirty artifacts belong.’”

Archaeological Society Collections Manager Christina MacDonald said in an email that the society’s “involvement with the Chinatown collection is only as the archive facility that will accept the collection when it is ready to be curated.”

Neither she nor other officials with the society responded to calls and emails from New Times seeking additional comment.

With no place to store the materials or work on the collection, Parker reached an agreement with the city to use a vacant Adobe, the Butrón Adobe at the end of Dana Street.

When volunteers—many of whom were older or retired—saw their new working environment, all but about seven left the project.

When they first tried to plug something into one of the outlets, the electricity blew out. If someone wanted to use the toilet, they would have to turn on the water first before flushing, then turn it off again because the toilet leaked.

“If you sat on the toilet, you had to hold the wall because it wobbled around,” Parker said.

The adobe was also vulnerable to break ins. In one instance, intruders forced entry and stacked boxes in front of the front windows to hide from the surrounding neighbors.

Another time, someone went to a table where a volunteer had been carefully sorting small artifacts and swept everything onto the floor.

In the worst instance, Parker said someone took shipping jars from the 1880s that had been painstakingly glued back together from fragments and smashed them against the wall.

The security issue was brought up repeatedly with city officials, he said, but any fixes were only temporary. The city put up a chain link fence. When the fence was cut, the city installed wire mesh over the windows, but that didn’t work either.

“The last year I was down there, we said ‘screw this,’” Parker said.

He and his wife converted the living room of their Morro Bay home into a lab. Volunteers would come by a few days per week to continue the work and catalog the collection.

In 2007, Parker moved to Northern California, leaving the majority of the collection stacked and boxed in the adobe. After some convincing aimed at the city—which didn’t want any of the artifacts taken out of the area—Parker got the green light to work with a few boxes of material at a time. Every four or five months he would go back to the adobe, pick up a few boxes, work on the materials, and bring back the completed collection to the archaeological society. Each completed batch won Parker another payment of the contract, maybe $1,000 or so each time, he said.

That was the way the project progressed for years.

Michael Codron, who was appointed as assistant city manager in 2010, said he began contacting Parker early on, trying to expedite the project.

“What the hope was … was that more progress would have been made,” Codron said.

Then he contacted Parker again in January of this year and asked for an estimate to finish the project, even though Parker was still under the original contract. In response, Parker said it would take an additional 10 months with a new team at an estimated cost of $117,120.

Considering that price tag, the city chose instead to close out the contract. Parker received a final payment of $8,500 and was asked to return the remaining materials. He turned over all of the data that had been entered into a proprietary computer program, as well as a preliminary report on the analyzed artifact features and history of the project, and drove the boxes he had from Lucerne to SLO.

That’s when things got complicated.

On Aug. 29, Parker wrote an email to a Caltrans official in charge of cultural resources.

“[Codron] told me that the materials were no longer at the Dana adobe,” Parker said, adding that he was told Caltrans had assisted in moving the materials, but no one would tell him to where. “That freaked me out, since I had organized and arranged those materials in feature groups for easy access.”

The email ended with one word: “Puzzled.”

In fact, all of the materials, including the completed collections with the SLO County Archaeological Society, were gathered and given to a new team: the Anthropological Studies Center at Sonoma State University.

“Some of the material I will tell you—let’s say about maybe 30 percent or so of the material—has already been cleaned and processed and cataloged,” said Adrian Praetzellis, a professor of anthropology and director of that school’s Anthropological Studies Center. “The remainder was in less than that kind of condition.”

SLO transferred the Chinatown project to Sonoma State on July 7 for an initial payment of $10,000 to transport the collection and develop a plan “for its stabilization.”

For Parker, the issue isn’t that he was taken off the project, but that he wasn’t consulted when the materials were moved. He told New Times that everything in the adobe was organized in a way that only he could decipher, and that any other team might risk mixing things up.

“My main concern is to see that this collection is cataloged and analyzed properly, and I am just afraid that without my guidance, I don’t think that someone can come in and do it,” he told New Times.

City officials explained that the contract with Parker had carried on too long, and the new team was better suited to finish the necessary work. But when asked about the condition of the artifacts and security of the adobe, they sometimes gave contradictory responses.

“The collection was definitely not being served very well stored in the Dana adobe,” said Principal Analyst James David. “There were some signs of deterioration. … It was kind of a situation where we needed to act on this or else it might get to the point where we could lose some valuable resources.”

Codron said “the adobe was a secure location,” adding that the materials were safe from “further deterioration” and “at the time that it was transported there was no reason to believe there was anything missing.”

Parker took issue with the notion that the artifacts in the adobe might not have been properly stored and maintained.

“It wasn’t a rotting and stagnated collection of stuff; it was boxes of archaeological materials recovered from excavation,” he said. “… It’s so frustrating for me, realizing that they could easily have called and said, ‘We’re going to open up your lab building and turn over all this stuff to Sonoma State. … Can you come and help?’”

What no one disagrees on is that the collection will be well cared for by an experienced team.

“The important thing for people to know is the collection now is in good hands and we’re moving forward to complete the catalog,” Codron said. “That’s the most exciting part about this.”

According to Praetzellis, he has a team of students helping to clean and sort the material—some may even use the Chinatown artifacts for their thesis projects. And they’ve already begun to uncover clues about the way people in Chinatown lived. Such an account was never included in historical documents.

“When you look at archaeological remains, this is really an unedited version of the past,” Praetzellis said.

Asked whether he’ll have to start from scratch or can continue the work Parker and his team began, Praetzellis couldn’t say for certain.

Under the terms of the contract, Praetzellis and his team will review the collection through the end of the year, then present a plan and estimated cost to the city for what’s needed to complete the project.

When Parker learned that the materials were moved to Sonoma State, he told New Times, “The Sonoma State folks are excellent.”

“They could easily do what needs to be done with that collection,” he said, “if they had known the order of the boxes and what’s sitting in front of them.”

But in a recent string of emails, Parker criticized the city for how it transferred the project.

“In case you don’t get it yet … it was never about the money, it was about recovering, analyzing, and writing that part of SLO’s past that was left out of the history books,” he wrote to Codron on Sept. 18. “It also doesn’t matter who does it, just that it is done right.”

He also admonished city officials for asking him to drive the remaining materials from his home in Northern California to SLO, when he could have more easily driven the 1 1/2 hours to Sonoma State.

“It’s a shame the way this year has gone with that collection,” he told New Times. “Because the information in that collection is amazing. It is amazing. … It’s basically the history of San Luis Obispo’s Chinese community, but I have no idea how they took that stuff out of there and what order it was in.”

Asked what lessons could be learned, Codron said he now realizes “the need to complete the project that allows that story to be told to the whole community, and we are on the path to doing that now.”

Though that story is once again getting pieced back together, it may be difficult to ever truly know what could have been lost. When asked about the artifacts that remain from the original Chinatown, Krieger (the local historian and columnist) said, “there’s such fractional remains that it’s difficult to build a historical narrative without better archaeology.

“And because the archaeology was not handled well at the beginning—we needed more time to do the dig—it’s an incomplete project. It’s going to be difficult to build on that.”

Senior Staff Writer Colin Rigley can be reached at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023