'The juvenile justice system is really a reflection of what's going on in the home ...'

By Kylie Mendonca[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

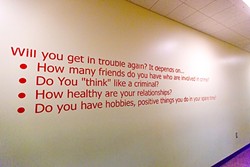

In the corridors of SLO County Juvenile Hall, a painted yellow line on the concrete floor dictates to inmates the appropriate path to follow—straight down the center, through locked door after locked door. Kids straddle that line as they shuffle between classroom activities, legal proceedings, and their tiny, cage-windowed bedrooms. It’s a sparse and serious place, punctuated by youth art projects and the distant beat of a basketball against pavement.

Harsh as it is, SLO’s juvenile hall is considered progressive. Juvenile justice is in the midst of an overhaul, a push toward rehabilitation rather than punishment, and SLO’s probation department embraces that ethos. For many kids in lockup, however, that shift comes about a decade too late. Lawmakers and enforcers are beginning to acknowledge that the path to criminal delinquency begins long before kids enter juvenile hall, probably before kindergarten.

The hall is home to about 27 local kids on any given day, and that’s about 50 percent fewer kids than were locked up six years ago. Back then, according to Chief Probation Officer Jim Salio, who oversees juvenile hall, the facility was so packed, kids had to sleep on the floor. Two things happened to sort out the crowding issue. For one, Salio and others inside the juvenile justice machine have grown reluctant to put kids in detention.

“Locking children up in juvenile hall doesn’t change behavior,” Salio said.

The second factor is that crime overall is down. According to a report by the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, youth crime is down 50 percent since 2000, and incidence of crime by kids under 12 has plummeted, down 92 percent since 1977.

Still, the war on youth-committed crime is far from over. In 2014 there were 520 bookings into SLO’s juvenile hall, down from 638 the previous year. In reality, the number of individual kids who are booked into juvie is much lower—277 kids did an average of 1.9 stints in juvenile hall. The vast majority of kids who get arrested are released the same day, and only a fraction end up in custody long-term. The problem is not widespread delinquency. Rather, it’s the persistent delinquency of a small group of kids. Those are kids who are more likely to have grown up poor, exposed to violent and harmful behavior, and whose welfare and safety were likely determined by the courts long before the law sought to protect us from them.

“The juvenile justice system is really a reflection of what’s going on in the home,” Salio said. “Every once in a while we see an outlier, but rarely do we see a kid who doesn’t have something going on at home.”

From the beginning

Salio’s sentiment was echoed by local attorneys who work with kids and by California Attorney General Kamala Harris. In February 2015, Harris launched the Bureau of Children’s Justice and called upon local agencies to re-evaluate the enforcement and oversight of children’s well-being (child welfare and delinquency are two sides of the same coin).

In a statement, Harris said, “We cannot let down our most vulnerable children today, then lock them up tomorrow and act surprised.”

The bureau’s stated goals are to address discrimination and inequities in education, elementary school truancy, as well as childhood trauma and exposure to violence, all of which are tied to delinquency. So is race. Statewide, young men of color—black and Hispanic kids—are vastly overrepresented in the justice system. Of the nearly 87,000 kids arrested in California last year, more than half were Hispanic and nearly 20 percent were black. White kids represented about 22 percent of the total arrests, according to the attorney general’s 2014 report on juvenile justice.

In SLO County, however, more than half the kids referred to the Probation Department were white, according to statistics from the county Probation Department. The numbers, though, still aren’t consistent with the county’s makeup. Not accounting for differences in birth rate, SLO County’s population is about 70 percent white overall. Hispanic kids accounted for 36 percent of kids referred to probation, and black kids made up 4 percent. Hispanic or Latino people make up about 22 percent of the county’s population, and black or African-Americans represent about 2 percent. Across all races, young men make up about 75 percent of all juvenile arrests in the county.

When the Bureau of Children’s Justice launched this year, it released a “fact sheet,” basically to justify the bureau’s creation. It reads like a trail of breadcrumbs, leading the way from childhood, to delinquency, and ultimately to adult incarceration. Consider this: In the 2012-2013 school year, 250,000 elementary students in California missed at least 10 percent of school days, and 90 percent of those kids were considered to be from low-income homes.

In the last school year, almost 25 percent of all African-American kindergartners and 14 percent of all Latino kindergartners in the state were chronically absent. More than 80 percent of chronically absent kids were below proficient reading levels by the end of third grade. Kids who aren’t proficient readers by third grade are four times more likely to drop out of school than the general population. Finally, 82 percent of prisoners in America are high school dropouts.

Switching sides

To her credit, Attorney General Harris is seeking out the root causes of delinquency and making the connection between child welfare and criminal behavior. Juvenile courts are divided into two parts: dependency and delinquency. If a child is removed from their parents’ home, or in some way needs assistance from the court, they are on the dependency side. If a child’s facing punishment for a crime, they are on the delinquency side. One judge in SLO County presides over all juvenile cases, and a handful of lawyers represent kids in both delinquency and dependency cases.

In SLO, kids can only be on one side of the law at a time, but it’s common for kids to switch sides. Local attorney Theresa Klein, who has represented kids in court for more than two decades, said it happens all the time.

“They’ll start out having troubled lives,” Klein said. “They’re ignored or abused as a child, and then as adolescents, they’ll end up being in trouble. The courts usually have a lot of compassion, because they recognize that this isn’t just a child who decides to be bad.”

This is a somewhat revolutionary idea in youth justice. Juvenile crime peaked in 1997, according to the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice. In 2000, California voters passed Proposition 21, which made it easier to prosecute kids as adults. Critics of that tough-on-crime attitude say it didn’t acknowledge the malleability of kids—their ability to change emotionally and physically, and the propensity among all teenagers to be delinquents. Fortunately, that style of justice is on its way out.

“We’re better at assessing risk, and not criminalizing kids for adolescent behavior,” Salio said. “It’s about risk assessment, not ‘commit the crime, do the time.’”

Kids who commit random acts of delinquency are frequently enrolled in a diversion program. It’s a type of informal probation program that kids can graduate from with no permanent criminal record. Few kids who are already on the dependency side of the system are candidates because, Klein said, if they’re already in trouble, they’re unlikely to succeed.

“I have clients who are committing crimes, but they’re not in the system yet,” Klein said.

When a kid in the dependency system begins committing crimes, they’re usually counseled and mentored. There’s a slow escalation of punishment and intervention. If a kid continues to get into trouble, eventually a judge will decide to boot them to the other side of the law. It’s sort of a last resort.

There are certainly critics of this style as well. Giving kids more and more chances doesn’t always lead to a better outcome, because once a kid’s in the system as a delinquent, they’re under intense scrutiny. Normal teenage bad behavior, such as disobeying parents or cutting class, can land a kid in lockup. In fact, in SLO County, more that half of all kids who found their way into juvenile hall did so by breaking a probationary agreement, rather than committing a new crime. That type of recidivism is about four times higher in this county than the rest of the state.

A head start

So are we soft on youth crime or hard on crime? The real question is how did California’s juvenile crime rate fall so low, despite a recent recession, even. No one knows for sure, but many people suspect early education is responsible. Programs such as Head Start, which offers educationally enriched day care, preschool, and (non-monetary) support for low-income families, are thought to have a huge impact on kids’ lives. A 2001 longitudinal study on youth in Head Start found that kids who participated in the program were 33 percent less likely to be arrested over their lifetime than their peers who got no preschool.

And, if that’s true, it comes at a bargain. In 2014, county probation spent $9.7 million on juvenile services and juvenile hall. They’re also expanding the juvenile hall, despite existing empty beds, to house kids with mental health problems and drug abuse problems. The expansion is supposed to keep more troubled kids closer to home. Head Start programming, by contrast, cost $7.6 million in 2013, according to the program’s 2013 annual report. That money supported and educated more than 800 kids around SLO County that year.

Bill Castellanos, who serves as division director for Child, Youth and Family Services with CAPSLO, (local Head Start programs are administered by CAPSLO) said he has no doubts about the success of Head Start. He’s worked with low-income and troubled youth since the ’60s, when his clients were young gang members in East LA.

“I know for a fact, from experience, that it works,” Castellanos said.

What makes Head Start successful may be the whole-family approach. It’s not just day care; Head Start includes a lot of parenting guidance and life skills—like how to cook a healthy low-cost meal or set goals. There are programs for pregnant women, migrant children, and homeless families. Kids gain reading and social skills, as well as health and dental care through Head Start. Unfortunately, the need in SLO County is far greater than the program can accommodate.

“We do not have enough locations to serve the children,” Castellanos said. “I’d say that 60 percent of the children are being served, and 40 percent are not being served. I think funding is the main reason.”

Comparing budgets for Head Start and youth probation is a useful exercise in public accounting—do we want to spend on prevention or treatment? Ultimately, though, that little comparison misses the point that human lives are at stake.

While Attorney General Harris and others are trying to create a war on youth-driven crime, without declaring war on kids, compassionate justice, it seems, has limits. The number of kids being charged as adults has gone up since 2003—the first year in which there was robust data on the topic.

In California, kids as young as 14 can be charged with adult crimes and serve adult time in a regular jail. Since voters passed Proposition 21, more than 8,000 kids in the state have been moved to adult court, and about 75 percent of those kids are found guilty, according to juvenile justice reports. In 2010 and 2011, SLO County was above average in terms of youth transfers to adult court, according to the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice. The SLO County Probation Department reported a total of nine transfers those years. Between 2012 and 2014, 12 kids in SLO County were charged as adults. New Times was unable to obtain details about such cases from the District Attorney’s Office before press time. When children are prosecuted as adults, they’re no longer covered by the privacy laws that protect most children in the justice system. They’re no longer children, according to the courts. They’re not considered savable.

Local attorney Klein said that working with troubled kids can be emotional for everyone involved, from the judges to the guards at juvenile hall. When a kid finds his or her way back to lockup, or relapses on drugs, or winds up in the adult system, it affects everyone. When delinquency is viewed as a symptom of poverty and trauma, then professionals in the system often feel the sting of personal failure when another kid fails.

“I had this one who presented as real tough,” Klein said. “And then his grandma came into the courtroom, and he just fell apart. ... They’re all savable.”

Kylie Mendonca is a staff writer for New Times. Contact her at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023