[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

A Cal Fire pickup truck carefully drives up the chalky dirt road toward the East Ridge of the Cuesta Grade on Aug. 21. Down below, Highway 101 and what’s visible of San Luis Obispo is a tiny sliver between rolling hills.

The truck’s headed for the top, so Bennet Millo, a Cal Fire public information officer, and Chip Laugharn, a United States Forest Service public information officer trainee, can show New Times a bird’s eye view of how the Cuesta Fire moved and how it’s being fought.

A few fire engines—Cal Fire in red and the USFS in seafoam green—splattered with pink fire retardant sit beside the road, their crews are staying put, keeping an eye on progress and an ear tuned to the radio, prepared for a sudden turn toward the unexpected.

Miles north, somewhere near the boundary between the Los Padres National Forest and the Santa Margarita Ranch, the fire still smolders and flames in a drainage—an area between the hills where water sometimes flows, making it thick with brush, trees, and other fuels. There, crews continue the arduous, back-breaking work of wading through poison oak to cut trees, clear brush, and dig dirt where the fire still breaths, giving it fewer and fewer places to gasp as it tries to stay alive.

Pink flame retardant powders the jagged ridgelines, broad strips of barren dirt are torn through the brush, and helicopters take turns dropping buckets of water into the ravines while another hovers high in the air, mapping, scouting, keeping track of the moving parts.

The fire’s burning toward the Los Padres National Forest, threatening an area where it’s really hard to fight fire because of the thick fuel load, steep hills, and difficult accessibility

“It’s not rolling hills and oaks and little pieces of grass that were chewed up by cows,” Laugharn says.

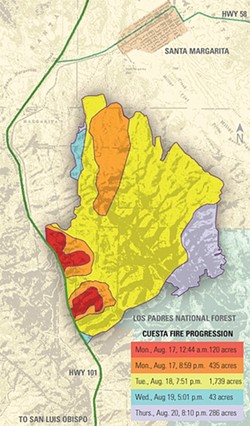

Just five days before, in the evening of Aug. 16, a pair of small fires officials say were sparked by a vehicle merged, roaring up the steep East Ridge hillside to its summit. By the next day, it had doubled in size, in part because very dry conditions and a northeastern wind helped it jump and spot ahead, going straight at the town of Santa Margarita, which by then was under evacuation orders.

In order to prevent the fire from hitting the town, an enormous prescribed burn was lit a quarter mile from Margarita’s edge to burn back to the fire.

While the worst had come and gone, there was still much work to do. In another five days, the fire will be all but contained.

When the fire spread and danced around, a well-orchestrated multi-agency effort and intermittent cool, foggy nights helped keep it from becoming an all-out rager. Still, dry drought conditions and the steep wild terrain continued challenging firefighters.

“How do you fight a dragon with a sword?” Laugharn says. “You have to outsmart it.”

Laugharn, a former Hotshot currently based in Pozo, joined the Forest Service shortly after the 1994 Highway 41 Fire. Started by an arsonist along Highway 41 between Atascadero and Morro Bay, that fire ripped south to the grade and threatened both San Luis Obispo and Santa Margarita, but never made it to either town after what’s recounted as a miraculous turn of events.

For the Cuesta Fire, if the week had seen a longer heat spell, things may have gotten more intense.

“Had that been the weather trend, we might not have had the success,” Laugharn says.

The Cuesta Fire was uniquely ferocious, mimicking this year’s fire behavior throughout drought-stricken California. Several firefighters said they’ve never seen this kind of fire behavior—where it’s commonly spotting ahead of itself, in which the wind picks up embers from very dry vegetation and starts several small fires. Oak trees, which don’t always burn, fell down and caught fire more than they usually do.

“The quantity that they’re burning and the quality that they’re burning is unprecedented,” Laugharn says.

The fire’s behavior made it both tricky and dangerous to fight.

“You have fire here, fire there, fire everywhere, and it’s really hard to keep track of all the fire lines,” Cal Fire’s Millo says.

At the peak of the fire’s threat, suppression efforts swelled to 1,858 personnel, 122 engines, 59 hand crews, 28 water tenders, seven helicopters, and two air tankers. All told, the fire burned 2,446 acres, and it cost almost $14 million to contain.

The steep terrain and dense vegetation of the national forest—some of which carries a wilderness designation that bars several activities inside its boundaries and restricts the use of heavy equipment—makes fire difficult to control.

“Just think about it. Wilderness to me means a designation of land. Wilderness to the public is a wild land,” Laugharn says. “The land kind of is telling man, ‘Stay away from here.’”

Fire loves to climb uphill, and does so very quickly. The rugged terrain and lack of roads mean crews need to spend hours hiking to their target spots, and then they start digging and cutting. The possibility of shifting winds and the availability of dense fuel loads create a potentially dangerous situation should the fire unexpectedly change.

Instead, tactics turn to intensely defensive approaches like prescribed burns, where bull dozers create large fuel breaks as the edge, and fire is intentionally set, hopefully starving the blaze of fuel needed for its spread.

Running a dozer through designated wilderness areas requires special authorization from the USFS regional office. Knowing the logistical risks at hand, that request was submitted as a contingency the night the fire started.

“They made the decision, and instead of waiting for that narrow time window, they put the plan together and fired it off,” Laugharn says.

Part of the reason that the Los Padres National Forest has so many restrictions, Laugharn says, is because it’s a watershed forest, an integral part of supplying water to area reservoirs. That means when firefighters are on the ground in the heat of the moment, plans are one part protection, one part defensive destruction.

Sitting in the truck, looking at the fading smoke on the horizon, that statement seems simplier than it probably is.

“We have to be right on that knife’s edge, right at that ridgeline, to do what’s best for everybody,” Laugharn says.

Online extra

View a fire history map of California. COURTESY OF SLOCOUNTYFIRE.ORG.

Contact Staff Writer Jono Kinkade at [email protected].

-- Melody DeMeritt - former city council member, Morro Bay

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023