No easy fix: SLO's embattled Rental Housing Inspection Program faces an uncertain future

By Peter Johnson[{

"name": "Newsletter Promo",

"id": "NewsletterPromo",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "4",

"component": "15264767",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "0"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

“I want to start by painting a picture of the house that I live in.”

Sean Cuccia, a Cal Poly student and San Luis Obispo renter, is standing up at the podium in SLO City Hall, addressing the City Council on Nov. 1. Blond hair with a buzz cut and an unassuming demeanor, Cuccia has a page of notes with him, but rarely glances down at them as he speaks.

“I pay $3,400 per month between me and my three roommates,” he says. “We literally live in a shack that is not hooked up legally to the electric grid of our city. The realty company, Cal West, repeatedly asks us to pay for things, sometimes without reimbursement. My toilet literally burst a hole in the side of the water tank. They were mad I hired an outside plumber, but it’s because when I called them, the lady that normally handles those things wasn’t in. And the problem is, she’s never in. … The electrician couldn’t figure out how to wire our stove to the house’s grid because it’s so convoluted and screwed up. And rent is literally the same as living on Balboa Island in Newport Beach, for a place that’s not worth what we pay for it.

“I understand the Rental Housing Inspection Program is unpopular and expensive,” he concludes. “Just, on behalf of a lot of residents here who are getting railroaded by landlords demanding a lot for too little, I just simply ask that you protect our livelihoods and keep us in mind.”

Amid swirling suspicions, outrage, lawsuits, petitions, and politicking over the SLO Rental Housing Inspection Program [RHIP]—which mandates an inspection of every single-family and duplex rental in the city to check for health and safety code compliance—Cuccia’s comment likely served as a fresh reminder of why the City Council adopted it 18 months ago.

By many accounts, the conditions of some rental homes in SLO, which now comprise more than 60 percent of residential properties, have suffered from landlord neglect. Both tenants (many of whom are students) and permanent residents in neighborhoods are impacted as a result.

Tenants rarely complain. Whether that’s because they fear the repercussions, don’t understand their rights, or they just don’t care, no one knows for sure.

But in May 2015, the SLO City Council decided that complaint-driven enforcement wasn’t cutting it. In a 3-2 vote, the council passed the RHIP.

“I’ve watched the complaint system not work,” Councilmember Carlyn Christianson said before casting her vote in favor of the ordinance. “It’s almost unethical for me not to do something about what I know about the substandard conditions of a number of units in this community.”

The RHIP was controversial when it passed, and that hasn’t changed as it’s been rolled out. Community members argue ferociously over the appropriateness, effectiveness, and even legality of the program. Many fault the city for targeting thousands of rentals in the pursuit of a “few bad apples.” Others call it fundamentally invasive and discriminatory. Some say it has hidden agendas like generating revenue, “beautifying” the city, and pushing students out of neighborhoods. Tenants have testified to financial hardship from increased rents. Property owners have sued. An outgoing City Council member is circulating a petition to repeal it.

Come 2017, the City Council will most likely reform or abandon the ordinance. Newly elected City Councilmembers Aaron Gomez and Andy Pease campaigned against it, joining current Councilmember Dan Rivoire in opposition to it. That majority bloc could dictate where the RHIP goes from here.

Whether the program will disappear altogether or simply get amended remains an open question.

Years in the making

Mayor Jan Marx says the RHIP’s passage “sent shock waves through the city.” But maybe that shouldn’t have been so surprising.

Neighborhood groups like Residents for Quality Neighborhoods have lobbied the City Council to pass a rental inspection ordinance for “about 10 years,” said Carolyn Smith, a board member of the organization.

“We have had complaint-driven enforcement. But the problem is that never works,” Smith said. “Over the years we have seen our housing stock deteriorate, which is not good for any city.”

Marx, who is closing in on a fourth term as mayor and served as a City Council member between 1998 and 2002, is intimately familiar with the push for an inspection program.

“Residents have come forward for years and requested it,” Marx told New Times. “Part of the reason is the percentage of rental housing in the city of SLO has gone up: About 65 percent of the single-family residences now are rentals. What’s happened is investors have moved in—not physically moved in—but they’ve started purchasing these homes as investments, rather than places for people to live in themselves.”

As more and more neighborhood homes flipped into rentals over the years, one of the consequences was housing conditions declined, as did some landlords’ desire to pay for maintenance.

“We’ve been hearing from students for years about how they’ve been living in substandard housing conditions,” Smith said. “Doors and windows don’t lock; their heaters don’t work; they don’t have hot water; their plumbing is bad; their roofs leak—and the property owner won’t make any repairs.”

Residents for Quality Neighborhoods certainly isn’t making this up. Jana Colombini, Cal Poly’s student body president, told New Times many student renters struggle with paying premium rents for sketchy and sometimes unsafe properties in the city.

“Some rentals are, unfortunately, in not the best condition,” Colombini said. “And there is a limited availability of rentals. We’re unfortunately at the stage where we take what we can get. If you have a tighter budget, you are almost forced to have to live in these substandard rentals.”

SLO’s not the only university town in California to consider a rental inspection ordinance. The city of Santa Cruz runs a similar program.

“Many university towns will have rental inspection programs of some kind so that there’s some accountability in terms of providing people with decent living,” Marx said.

The neglect not only affects tenants’ lives, but it also breeds resentment in permanent residents who don’t appreciate living in “blighted” areas. Residents’ desire for an inspection program is tightly interlocked with long-standing tension with Cal Poly, particularly in terms of the student housing shortage on campus.

“Many of these problems would go away if Cal Poly would build more housing on campus,” Smith said. “They’ve kind of created these problems.”

That’s where Residents for Quality Neighborhoods’ motives are scrutinized. Outgoing City Councilmember Dan Carpenter, who opposed the ordinance and is now circulating a petition to repeal it, expressed concern with the organization’s fervor for policies like the RHIP and suspects an anti-student agenda.

“I believe the genesis of this came from them wanting to push students out of San Luis,” Carpenter said. “That’s a leap, but I say it because I watched that group. I’ve watched them categorically try to get us to pass ordinances that really restrict [students’] ability to be participants in our community.

“It’s a horrible agenda, but I feel it,” he continued. “I feel like, these people are not going to be happy until we push all of the students out of the city and onto the campus.”

Smith vigorously denied that agenda.

“[The organization’s] mission has never been to get rid of students,” Smith said. “We just want everybody to coexist in safe and peaceful conditions. This RHIP is just another Band-Aid to try and resolve problems that Cal Poly is creating.”

After a decade of trying, the program finally materialized. According to Residents for Quality Neighborhoods, the RHIP found its wings in 2012, when the city hired Joseph Lease as chief building official. Lease came with direct experience implementing a housing inspection program in San Bernardino. Smith credits Lease for laying the groundwork for SLO’s program.

“He came in and put together this program with a lot of outreach to the community,” Smith said. “He wanted to make it feasible and acceptable to everybody.”

But Lease left the city in 2014 before his program was adopted and implemented. Anne Schneider took his job. Smith observed a “disconnect” in the handoff, noting, “It sounds like the implementation of this program may be a problem.”

Big program

When SLO Code Enforcement Supervisor Teresa Purrington verbally walked New Times through a typical rental inspection, she cringed slightly at some of the trigger points of tenant discomfort—perhaps a reflex from what actually happens in the field.

“We don’t go into closets, unless an electrical panel is in there,” she emphasized. “We look under sinks for leaks and holes, so no rodents can get in. We do open windows; we want to make sure the windows work in all the sleeping rooms. We test for hot water and test the electrical outlets by the sinks to make sure they’re grounded. We do an exterior walk around making sure all the vent screens are in place. We look at the water heater … look at the roof from the ground.”

Purrington, who previously worked for the city of Ventura, was hired to oversee the RHIP, along with an administrative assistant and two new inspectors.

The scope and expense of the RHIP is one controversial aspect of it. With four new employees, the program cost the city a little more than $200,000 in 2015 to 2016. The costs are expected to rise in ensuing years as inspections ramp up.

It’s being financed through the annual registration fee paid by property owners ($65) and the inspection fees ($185 per inspection).

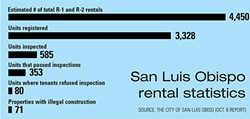

Despite the uncertain future of the RHIP, the inspections are in full swing. Purrington said her office is completing between 45 to 50 inspections each week. And as of Oct. 6, 3,328 out of an estimated 4,445 total units were registered to be inspected.

An inspection takes between 20 to 30 minutes, she said, depending on the size of the unit.

Basic health and safety is the name of the game. The inspection list is picked apart by critics for items that may go beyond health and safety (cracks in kitchen counters … floors that “could cause a trip hazard”), but the list appears to match up with the minimal habitability requirements outlined in state law.

The majority of units are failing the test on first try. Out of the 585 completed inspections, only 15 percent passed on the first inspection. Even after a second inspection, 40 percent didn’t pass muster.

Purrington said the most common reasons for failure have relatively simple fixes like missing smoke detectors and carbon monoxide detectors, unlabeled electrical panels, and improperly strapped water heaters.

“When you say it doesn’t pass, I guess that’s true. But we don’t consider that a fail,” she explained. “As long as the corrections take place, ultimately that’s the goal.”

Larger issues, like an unpermitted unit (say a garage) or “illegal construction,” which was the case for 71 units as of October, are more complicated.

A one-year “amnesty” period expiring in January allows these property owners to go to the city and be relieved of penalties.

“The city will work with the property owner on a transition plan to return the property to legal, conforming status,” a city staff report from May reads. “If a rental unit is safe to occupy but illegal for other reasons, the transition plan may enable the use to continue through the term of the existing lease.”

And if the unit is unsafe to occupy?

“The tenants have to vacate immediately,” Purrington said. “We let the property owner know that it’s their responsibility to help that tenant find housing, whether it’s putting them in a hotel or if they have another unit somewhere they can go to.”

As of Nov. 16, the city said the inspections have led to no tenant displacements.

Mixed experiences

Colombini, the Cal Poly student body president, is hearing mixed feedback from fellow student renters going through the inspections.

“When it works, it’s great,” Colombini said. “But on the other side, the inspector will come in, identify different problems, and then the landlord will charge it right back on the student. Those are the stories that are the most frustrating. … It falls back on the student yet again. And they’re right back where they started with having to pay for it themselves.”

She estimated the good and the bad inspections split down the middle.

“I think this program was intended for good … and intended to protect the tenants,” she said, “but there’s a few flaws behind it and I think maybe some sort of reform would be great.”

You can count Phil Hurst, a local business owner and renter, into the “bad experience” category. He rented a 116-year-old house on Story Street for 10 years that he loved. It had structural issues, but Hurst called it, “an affordable, deteriorated rental” and himself, a “grown man.”

“My 96-year-old landlady was born in the house,” Hurst told New Times. “There was no leaking; it wasn’t falling down. But we had chipped paint and chipped counter tops. The heater didn’t work. There was no fume hood over the stove. Half the foundation was original, so the floors sagged. Shingles were missing on the roof.”

Once the RHIP was being considered, Hurst started paying close attention to local politics. He said he knew his house would fail the inspection, and his elderly landlady would have serious trouble with the improvements.

After warning his landlady about the program, Hurst moved out of the house, and his roommate—his best friend—left the city.

“He couldn’t handle [the rent prices] anymore,” Hurst said. “[Mayor] Marx is out of touch. She doesn’t know what it’s like to rent in SLO. You have to get to the core of the issue. Why are people living in garages? Because there’s nowhere to live.”

The pushback

Longtime SLO realtor Steven Ferrario says the “slumlords” of SLO can be counted in “less than two handfuls.”

“If the city wanted to attack those people, it’d be pretty easy to do that,” Ferrario said. “There’s no reason to implement a million-dollar program to handle a problem that’s less than two handfuls.”

That’s a feeling shared by a number of landlords and property managers in town who are generally unhappy with the program. Ferrario decided against registering his properties with the city on principle alone.

“The city is not going to get my money,” he said. “The money is really inconsequential. And I’m not running something that’s not legal or to code. It really comes down to I’m opposed to the program.”

Mary Kirkpatrick, 81, has a similar view. A retired probation officer, Kirkpatrick bought her first property in SLO in the 1970s. She currently rents out six properties in the city, a few of which are more than a century old and on the city’s historic registry.

After enrolling in the RHIP, Kirkpatrick said her tenants were alarmed when they received a letter in the mail notifying them of a scheduled inspection. All 14 of her tenants ended up signing a ‘refusal to entry’ form—which is an “out” the city wrote into the ordinance for tenants. In those cases, the city says it will wait until a tenant’s lease is up to conduct the inspection.

“I didn’t have to say, ‘Boo!’ to them. They didn’t want an inspection,” Kirkpatrick told New Times. “I’m dumbfounded that as old and historic as SLO is, they’re after people of my age that have owned property forever. We’ve been good landlords. I’ve had tenants that lived in places for 11 years or more. I just don’t understand what the city thinks they’re doing other than raising money.”

The outrage of property owners isn’t just anecdotal. On Oct. 13, the SLO Property and Business Owners Association filed a lawsuit against the city in retaliation to the RHIP. The lawsuit—which has multiple plaintiffs including individual landlords Steve and Janine Barasch, Matt and Jean Kokkonen, and one tenant, Kevin P. Rice—claims that the program violates the Fourth Amendment (illegal search and seizure) and equal protection laws since properties with three or more units aren’t subject to the program.

At an association luncheon at Café Roma where the lawsuit was announced, members feared the ordinance would be a stepping-stone to rent control.

The city told New Times it will defend itself against the lawsuit.

The city may also have to answer to outgoing Councilmember Carpenter’s petition to repeal the RHIP. If Carpenter can collect signatures from 15 percent of the city’s residents before March, he “can take it to the City Council.”

“Then they can either adopt our initiative or they can call for a special election,” Carpenter said.

‘Overzealous’

Beyond the principled opposition, the RHIP raises suspicion among property owners about how the city will wield its power once an inspector enters the front door.

“We’re giving the city a free look into our property to find anything and everything,” Ferrario said. “The big gray area here is in the interpretation [of the code], and the fear is the city will come in and start demanding improvements to the property. It’s a slippery slope.”

That scenario is playing out in Kathie and Steve Walker’s home on Fredrick Street. The couple bought the house in 2009, and they rent out a guesthouse unit to help pay the mortgage. While the home is old and could use a remodel, it passed an inspection at the time of purchase.

The Walkers set aside $70,000 for improvements, but Steve, a pilot, seriously injured himself in a flying accident and the medical bills drained that fund. Kathie also suffers from a disability.

For the Walkers, it wasn’t the RHIP that called an inspector in but an estranged family member, who began submitting complaints to the city about the house’s condition. In May 2014, a building inspector arrived and cited them for missing building permits on construction dated back before they bought the house and other violations (like lacking a kitchen sink). The city demanded new permits and renovations that were “cost prohibitive” for the family with two boys.

“This room needs to be demolished,” Kathie said as she walked New Times through a pretty normal-looking bedroom.

Kathie recalled the inspector taking “hundreds” of photos of their home, and then they were hit with the notice of violations. They appealed, but lost.

“I’ve gained 60 pounds and aged 10 years in the last two years,” Kathie said.

Since they were subject to an inspection before the RHIP passed, the Walkers feel like they’ve been given a preview of what’s to come with the program and the city’s “overzealous” approach to code enforcement.

“Everybody else dealing with the program could have a bigger nightmare than we are,” Kathie said.

A new direction?

City Councilmember Rivoire knows firsthand the difficulty of renting in SLO’s market. The 31-year-old tenant remembers the nightmarish battles he had with prior landlords who refused to take care of basic needs on his property. While he’s in a better situation today, Rivoire still understands the fundamental uncertainty involved with being a tenant.

That was a big reason why Rivoire voted against the RHIP, which he felt was too big, too risky, and had the potential to be ineffective at the end of the day.

“I really felt that further intensifying the fragile nature of a renter’s lifestyle and exposing them to potential increases in rent—which are already out of hand—outweighed the positives of the program,” Rivoire said.

Rivoire was elected to the City Council in 2014, coming on board while the RHIP was already half-baked. At the time, he proposed dealing harsher penalties to irresponsible landlords but the idea never came to fruition. He hopes that can be better addressed in the upcoming deliberations.

“We need to have more severe consequences for bad behavior, and I don’t think this [RHIP] will really eliminate the bad behavior,” Rivoire said. “The owner of a home is still able to kick the can and delay action for an extended period of time. That to me is a disappointment.”

Newly elected Councilmembers Pease and Gomez share similar perspectives. Pease told New Times she thinks the program must be “suspended” and said, “The part of the program where every property is inspected has been the most problematic.” Gomez feels the program, “needs to be far more targeted towards those who are putting renters in unsafe living conditions.”

“I don’t think we need a program this big,” Rivoire agreed. “I think we can do this work with a scalpel and have quite a successful campaign.”

Time will tell how the city decides to change course given all the moving pieces. Residents for Quality Neighborhoods will advocate for keeping the program.

“We don’t want it to disappear,” Smith said. “We just want it to go back to what it was originally intended to do, and that’s to cover those basic safety things.”

Mayor Marx said she’s open to changing the program, but wants more detailed information about its impact, like a program-wide survey, to make future decisions.

Marx also talked about the city of Berkeley’s ordinance, the Rental Housing Safety Program (“It’s a better title,” she said), where landlords are required to provide a checklist of safety items to the tenant, who is then encouraged to report any missing items to the city if the landlord doesn’t address them.

“It puts the emphasis on the communication between the landlord and the tenant,” she said. “The city is still saying to the landlord and tenants, ‘This conversation has to happen.’”

Barring an eleventh hour push by mayoral challenger Heidi Harmon to win the seat, Marx herself will be leading the policy conversation going forward as the city’s re-elected mayor.

“The question is: Is the program a good fit for the city of San Luis Obispo?” she said. “There are a number of people who feel that it isn’t. That’s been pretty obvious.”

Staff Writer Peter Johnson can be reached at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023