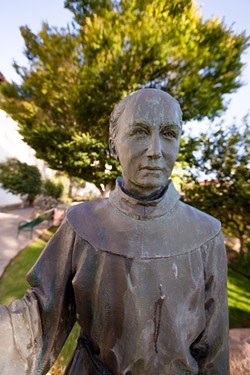

Mission to sainthood: Recently canonized Father Junipero Serra helped establish the California mission system, but is he really saint material?

By Sean Mcnulty[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

Washington, D.C., stands some 3,000 miles from the site of Mission Carmel, once the home base of Father Junipero Serra, an evangelist Franciscan from the island of Mallorca.

With a bum leg and a handful of starving Spaniards, that tiny priest founded a backbone of missions in what was then called Alta California—a massive hinterland of shrubs, oak, and sun—to stake out a distant colony on the remote edges of a dying empire.

Although the mission system was established in California, Pope Francis canonized Father Serra in D.C. on Sept. 26 as part of his first mass in the United States. The Pope avoided Carmel—where Serra died in 1784—some told New Times, because plenty of Californians don’t think the church should have recognized Serra as a saint. Fred Collins, chairman of the Northern Chumash Tribal Council based in SLO County, said the canonization is troubling.

“Nothing’s changed. It’s dehumanization of indigenous people around the world,” Collins said. “[Serra’s] job was to enslave the indigenous people. … It was really a colonization and a genocide all wrapped together.”

He said people who believe Serra is a saint talk about the “good” things he helped bring to California such as architecture, structure, engineering, and farming. What they don’t talk about is how all of those things were accomplished.

“We were doing the work, and we were doing the work unwillingly, as slaves,” Collins said. “You know, a lot of our people are Catholic, and it tears them in half to have to deal with something like this.”

During the ceremony outside the Basilica of the National Shrine of Immaculate Conception, the pope portrayed Serra’s legacy as one of a protector of early Californians, not as an oppressor and conqueror.

To over simplify, it seems like you’re either with the pope or against him. On the pope’s side of the great saint debate, people think Serra was a fervent believer, driven to accomplish things for his faith at a great cost to himself and that he demonstrated extraordinary compassion. On the other, people believe he was a sadist, a zealot, and an enslaver who was party to genocide.

Serra’s from another time, a period that’s alien to contemporary society and hard to understand. When he became a priest he took the name of an early Franciscan—an order of priests founded by St. Francis—who would give away all his clothes and walk naked in public. Serra’s a strange dude, he prayed to a flying blue nun that was miraculously able to be in two places at once, whose likeness was carved above the altar of his childhood church. The priest traversed much of Mexico and California on a festering leg that never healed.

His canonization raises questions that look at more than the time he spent on this earth—questions that stem from the legacy of the mission system and what it did to California’s native populations. The missions he helped establish sought to convert native people to the Catholic faith, and more often than not used those same people as a sort of slave labor force to keep the missions going. Disease and death followed.

Slaver or savior?

One of Serra’s loudest critics is Norma Flores of the Gabrilleño band of Mission Indians in the Los Angeles Basin. She’s the public face for a group of people who led the charge against Serra.

He was, she said, the “Adolf Hitler of California.”

Spain, Flores said, had “a fine-tuned extermination machine under the guise of evangelism”—meaning she’s accusing the Spanish of willfully decimating native populations for the purposes of colonizing California with priests leading the charge.

“This is deep,” she said. “It’s not just one Spanish guy.”

Her list of grievances is long. She said soldiers were sent out to rope native women like cattle and take them back to the missions; they separated men, women, and children; and, at the hands of the Spanish, the natives were raped, whipped, and forced to work.

Eventually, as Flores tells it: After being robbed of their culture, riddled with European diseases, stripped of their lands and sources of food, and crushed under the heel of the invaders, the native population of California fell to 10 percent of what it once was.

“If the Confederate flag can be taken down, then statues of Junipero Serra can be taken down also,” she said. “What’s innovative about slavery? Junipero Serra brought slavery to California. He did not treat our people in a loving, compassionate manner that was in line with the teaching of Jesus Christ.”

Flores was raised in a Catholic family. She was baptized and raised in the church. “But my mother, who is native, did not want me confirmed,” she said. Why? She didn’t want her daughter to be slapped by a Catholic priest, Flores explained.

And she added that the canonization of Serra, like the rites of confirmation, is “a final slap in the face for native people.”

She pointed to a letter written by a French sea captain who visited Mission Carmel as an example of how poorly native Californians were treated. The captain compared what he saw to slavery in the Caribbean.

“We have seen both men and women in irons, and others in the stocks. Lastly, the noise of the whip might have struck our ears, this punishment also being administered, though with little severity,” he wrote.

“If he escapes to reside with his relations in the independent villages, he is summoned three times to return,” the letter continues. “If he refuses, the missionaries apply to the governor, who sends soldiers to seize him in the midst of his family and conduct him to the mission, where he is condemned to receive a certain number of lashes with the whip.”

Flores wants that whip to descend on Serra’s legacy.

“We seek justice,” Flores said. “Justice has no time limit.”

The Church

A phone call to Mission Santa Barbara—the only California mission to be continually occupied by Franciscan friars—yielded no comments to questions about Juniperro Serra’s upcoming canonization, but New Times was directed to speak with Franciscan Father Ken Laverone of Mission San Juan Bautista.

Laverone said Serra saw himself as a father to native Californians—and saw whipping as acceptable discipline.

“By today’s standards, you don’t do that. Serra was a man of his time, and he brought means of fatherhood, of parenting with him. Was his intention to hurt the Indians? No. It was to teach them God’s love. But from the perspective of the 18th century, he did,” Laverone explained.

Still, he said, Serra saw Indians not just as children, but as human beings, sometimes where other Franciscans didn’t.

“I think the church sees him as a great evangelizer, as someone who left everything he knew,” Laverone said. “He had terrible physical problems, and he still carried on, he never stopped. Not for his own good, but for what he believed was the good of people, was the good of souls.”

The force with which Serra pushed through those setbacks opened up the door for the Spanish colonization of California.

“You could not separate the evangelization from the colonization,” Laverone said.

Mercy

That colonization made the California we know today, and SLO’s Dan Krieger knows how that went. Krieger’s Catholic, an active part of Mission San Luis Obispo, and also a professor emeritus of history at Cal Poly who’s studied the mission system “since I was 8,” he said.

Krieger recognizes that colonialism is deplorable. His historical understanding is that political turmoil in Europe had the Spaniards looking to expand into California. He thinks Father Serra and his Franciscan brothers, while complicit in colonization, did their best to protect and minister to a native population caught between the ravages of disease and the brutality of the Spanish military.

He sees Serra as a compassionate man. In one incident, Krieger recounts a story about a high-ranking Spanish official—Fages, the military governor of California—who wanted his soldiers at the Spanish fort in Monterey to have access to native women.

Serra responded by moving the mission 9 miles south, away from Monterey’s Presidio, so the soldiers wouldn’t get that access. He went over the heads of his superiors, pushing back hard against Fages, writing directly to the viceroy of New Spain (now known as Mexico) that “I am bringing your military governor down and he will be tried in court, and if necessary, punished by civilian authorities.”

Krieger also points to an incident in 1775. A man was accused of killing a priest and good friend of Serra’s in San Diego. Serra, once again going above the heads of his superiors, demanded that the accused not be put to death.

“Saints are people of their time and have to be judged in the context of their era. How did they behave? What qualities did they exemplify? Their purpose is to set examples in empathy, charity, and the crusading spirit of trying to change the world for what it is,” Krieger said. He sees the idea, in Serra, of “never giving up. He may have had a misapprehension of God’s cause.”

Chuckling, Krieger added, “Most of us do.”

Discipline

In the debate over saintliness, whipping is a sticking point. Most of us don’t think new converts to a church should be whipped, but many converts to the mission system were. One neophyte (a new religious convert) named Francisco was tied to a whipping post in front of Dolores Mission—where, according to Krieger, the unlucky spectators “had to watch as [Serra] gave 25 strokes to poor Francisco.”

It should be kept in mind the fathers used thick whips of cord, which does not generally break the skin, instead of leather, which does. Soldiers were also whipped as punishment.

Krieger emphasized that the historical record shows no Indian beaten to death or flayed under the Franciscans. And, he added, common punishments at the time were horrific by comparison—like keelhauling, where sailors were dragged along the barnacles under a ship so that their flesh was torn to pieces.

Serra, like many Catholics of the time, mortified his flesh—he did the whipping himself, with chains or a leather cord, until his skin broke open and bled. The Vatican didn’t turn away from mortification of the flesh as penance until the late 1960s.

The San Diego History Center’s account of a sermon in Mexico describes Serra drawing out a chain, asking his audience for penance. He “began to beat himself so cruelly that all the spectators were moved to tears.” One spectator came up to the altar, took the chain from the father, stripped to the waist, and beat himself while sobbing and asking for penance.

“So cruel and pitiless were the blows,” it reads, the man fell down. His last rites were administered and he died on the spot.

Disease

It was the staying power of disease, not the lashes of a whip, that devastated the native population. John Johnson, an anthropologist at the Museum of Natural History in Santa Barbara, said the tragedy of the mission period is not how the Catholic priests treated the native Californians.

“No punishment was given to them that was not given to the soldiers,” Johnson said. “Colonization introduced diseases that were devastating to the native peoples that had no natural immunity.”

By the end of the mission period in 1833—70 years after Serra’s arrival in California—Johnson estimates that the native population shrunk to a tenth of its pre-contact numbers.

“Most of that mortality was not major epidemics but childhood diseases,” Johnson explained. “Four out of five children born at the missions died before they reached adulthood.”

The Franciscans knew a little bit about medicine, but what they didn’t know was deadly. Krieger, the historian, said that they understood that quarantine worked against spread of diseases like the plague. But they believed that other illnesses were caused by vapors in the night air. So, they shuttered the Indians in small rooms with the windows closed, where bacteria festered.

Priests grew medicinal herb gardens and learned cures from indigenous peoples to stave off sickness. This was some help. But they fed them beef, which led to osteoporosis, and had them drink milk, despite their lactose intolerance. Meanwhile, Spanish cattle chomped through the seeds that native Californians foraged for food, devastating their ability to live off the land.

Scholar Barry Pritzer writes that in the early 19th century, when the Mission period began to sunset, there were 200,000 indigenous people living in California.

Then, in 1834, the priests were kicked out and the Mexican rancheros came in; then the Americans from eastern states, seeking gold. Each group, according to Krieger, brought disease, racist ideologies, and a greater propensity to take what remaining resources the mission Indians had.

By the end of the 19th century, according to Pritzer, only 15,000 indigenous peoples were left in California.

Serra didn’t live to see it. “He was dead before any of that, before the high mortality began to take its toll,” Johnson said.

The Chumash

Ernestine de Soto, an elderly nurse in Santa Barbara, knew the last living speaker of the Chumash language more intimately than anyone else. It was Ernestine’s mother, who would speak it with her great uncle and the ethnologist John Peabody Harrington.

“That wasn’t a big deal like everybody makes it out like today,” Soto said dryly. “It was just an everyday thing in our household. We know what we were and that was the end of that. It was a natural occurrence to us.”

De Soto grew up in Watsonville, where there weren’t many Chumash around. “Frankly, I have to tell you, I thought we were the only ones in the world,” she recalled. Once, there were thousands, with Spanish explorers describing the shores of what is now Santa Barbara as thronging with Chumash.

De Soto is very Catholic—“they did their work well with us,” she said—and she heard that Serra would be canonized while she was working at Mission Santa Barbara.

“My first impulse was—‘Oh, my God.’ I have nothing against Father Serra, but it only meant that what happened to us was more or less justified, or OK. It was not closure,” she said.

De Soto was caught between her ancestry and her faith when her daughter ended up in the hospital. “She had a very bizarre cyptogenic pneumonia,” de Soto said. It wouldn’t respond to treatment, and her daughter wasn’t getting enough oxygen to her brain.

So de Soto did what a faithful person does: She prayed. And she prayed with a piece of Serra’s bone—a relic. As she tells it, Father Serra granted her the miracle that hundreds of doctors, nurses, hospital staff, and clergy couldn’t.

“She’s sitting in front of me, she should not be here—she’s a product of his miracle,” de Soto said.

Then, sounding weary, she paused. “I don’t think that everything would be rosy,” she said. “All conquering of civilizations—you must understand how it works. We’re doing it right now to other people. But it’s not something that I’m bitter about.

“I’m grateful for what we have left,” she added.

Staff Writer Sean McNulty from New Times’ sister paper to the south can be reached at [email protected]. Editor Camillia Lanham contributed to this article.

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023