Head game: SLO County's athletes focus on the detection and prevention of concussions in youth sports

By Peter Johnson[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

It could have happened anywhere, but it happened in PE.

Casey Lieberman, an avid soccer player from Arroyo Grande—known by her family and teammates for her willingness to put herself in harm’s way during games—was in class as a freshman at Arroyo Grande High School last February when a classmate drop-kicked a soccer ball from behind her at point-blank range.

“He underestimated my height,” Casey said. “And he kicked it into the back of my head.”

Without the opportunity to brace herself, Casey’s head snapped forward upon impact.

“I don’t remember it all that well,” Casey said. “I let myself down to the ground, feeling really nauseous. I was wheelchaired to the office.”

The school’s athletic trainer evaluated Casey and decided that her symptoms of dizziness and nausea pointed to a concussion.

A concussion is defined by the Centers for Disease Control as, “a type of traumatic brain injury (TBI) caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head or by a hit to the body that causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth.”

One of the many medical challenges inherent with concussions is predicting what will happen to a given individual after trauma occurs. Treating and managing a concussion is usually a matter of reacting to the situation at hand, as each circumstance and brain is unique.

Casey was no exception.

“We didn’t know anything at first,” said Nancy Allison, Casey’s mother. “There’s no way to know.”

Casey’s symptoms worsened in the hours and days following the hit. She developed an intense sensitivity to light and sound. After a few days of resting in a dark room at home, Casey tried going back to school. But the florescent lights and classmate chatter were too head-splitting.

“She was in bad shape,” Nancy said. “She slept a lot. She couldn’t walk without being dizzy.”

What could be more vital to health and fitness than the well-being of the head? Concussions are staying in the national spotlight after the release of the film Concussion, and they are the most commonly diagnosed sports injury in high school athletics. A report from the National High School Sports-Related Injury Surveillance Study found that concussions made up 25 percent of injuries in high school athletics in 2014-2015.

TBIs are on the minds of many local parents, coaches, and athletes as well, after the life-threatening head injury suffered by 16-year-old Isaac Lindsey of Templeton stunned the SLO County community.

Lindsey suffered a rare type of TBI—secondary impact syndrome—that takes place when a second concussion is sustained after the first one goes unnoticed. The brain is shaken by the next trauma before it has had time to fully heal from the initial one. While secondary impact syndrome has a fatality rate of 50 percent, Lindsey was lucky enough to recover after a weeklong medically induced coma and many weeks of rehab.

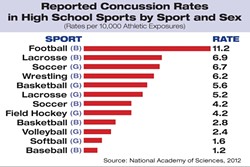

Concussions can occur in just about every physical activity, but they are suffered at varying rates depending on the sport. In organized youth sports, boys experience concussions at the highest rate in football. For girls, soccer holds the highest concussion rate.

Even though medical research on concussions has improved our understanding of the injury, and therefore our ability to manage them, concussions remain a nebulous phenomenon that can be difficult to detect and treat.

A different game

San Luis Obispo High School football coach Pat Johnston is barely 30 years old, but he is certain that the high school football he played in 2004 is very different from the sport he coaches today.

“A lot’s changed,” Johnston said. “We do things a different way now.”

A majority of those changes are about reducing the risk of TBIs in the sport. Football sees the highest rates of concussion in sports, at 11.2 concussions per 1,000 athletic exposures, according to a paper by the Academy of Sciences.

In January 2015, a new state law went into effect that restricts football teams to two full-contact practices per week. The law also requires any student athlete “suspected of sustaining a concussion” to be removed from play and cleared by a doctor or doctor’s office before returning to sports.

Tom Goossen, Arroyo Grande High School football coach, told New Times that he decided to cut down on “live” practices eight years ago, averaging only one or two full-contact practices per season.

“Doing the reading and staying up to date, I came to the conclusion that that’s a step I have to take,” Goossen said. “We want to reduce all amount of head trauma a football player will take.”

The rules of the game have also changed to discourage hits to the head. Referees are playing an increasing role in protecting the players on the field.

“The referees have done a pretty darn good job at enforcing that,” Johnston said. “They are being vigilant, along with the coaches and trainers on the sideline, of noticing the signs and symptoms of a concussion.”

Changes to make football safer also include teaching new tackling techniques. Since two-thirds of concussions in football take place in the act of a tackle, Johnston knows it is a coach’s responsibility to teach players to tackle with their heads out of the way.

“The technique is about taking the head completely out of the tackle, putting it behind the man instead of in front of him,” Johnston explained. “You can definitely see just in the way that you practice it that it makes a huge difference.”

One issue that coaches, athletic trainers, and parents cited as a worry is the tendency for players to withhold symptoms from adults in an effort to remain in the game.

Johnston, again, believes that problem falls on the shoulders of the coach.

“When it comes down to it, it’s what kind of culture is that coaching staff developing at that school?” Johnston said. “Are they developing one of blind toughness or communication and trust with the coaches? There’s something to be said for that.”

Club sports are another arena that many youth athletes participate in. According to referees and coaches in the club soccer scene, high schools are further along in concussion management than clubs.

“The high schools have been doing a great job longer than other leagues have,” said Chris Doucette, director of referee instruction for the American Youth Soccer Organization (AYSO) Five Cities region. “There’s no athletic trainer out there at a competitive club match.”

Doucette asks all his AYSO soccer referees to complete an online concussion course as part of their training, even though California doesn’t mandate the training for referees yet.

“Other states do,” Doucette said.

Cal South, another competitive local soccer club, requires all coaches, managers, and athletic trainers to complete a concussion training course.

Doug MacMillan, a longtime local club and high school coach, believes that the increased awareness and education for soccer coaches, especially on the threat of secondary concussions, is having a healthy impact on the sport.

“Everyone knew of concussions, but we didn’t know that once you have a concussion you’re 1,000 times more vulnerable [to compounding effects of multiple concussions],” he said. “I think that’s the wake-up call for coaches.”

Soccer sees the highest rate of concussions in girls’ sports, at 6.7 concussions per 10,000 exposures, with about two of those statistical concussions taking place in the act of heading the ball.

U.S. Youth Soccer, the largest soccer club in the country, recently banned headers for players under 10 years old. While that rule has yet to trickle down into leagues not under the umbrella of U.S. Soccer, it may not be long before the policy is adopted universally.

“That’s a brand new thing,” Doucette said. “It’s not in the AYSO rules yet. We’re curious about where that’s going.”

Trained for it

Nancy, Casey’s mother, believes that children should be encouraged to follow their passions when it comes to sports.

“My philosophy is you got to let your kids play something if they’re passionate about it,” she said. “Life has certain amount of risk. I don’t think you need to restrict kids from playing a whole sport.”

The biggest risk with concussions comes when they go unnoticed. Because many of the symptoms of a concussion are also common ailments of everyday life, it requires the keen eye of a coach, athletic trainer, or parent in addition to honest communication from the athlete to identify a concussion.

Stacey Ritter is the director of sports medicine and athletic training for San Luis Sports Therapy, a company that contracts with eight SLO County high schools—Paso Robles, Templeton, Atascadero, San Luis Obispo, Mission Prep, Morro Bay, Arroyo Grande, and Nipomo—to provide each school with one qualified athletic trainer.

“Not all concussions are serious, but every one needs to be taken seriously,” Ritter said. “Some of them are minor and heal up just fine with the appropriate steps and management.”

Symptoms of a concussion include headaches, nausea, dizziness, blurry vision, sensitivity to light and noise, sluggishness, trouble concentrating, and confusion.

“The most challenging thing is if an injury occurs and either an adult didn’t see it or an adult who did see it doesn’t report it,” Ritter said. “Even more important is when the athlete doesn’t report it themselves. It really requires the athlete to communicate.”

The threat of multiple concussions is most troubling. Concussions are not additive in their damage when suffered one after another—they’re compounding.

“If you continue to reinjure your ankle, the worst that may happen is that you may have a limp later on,” Ritter said. “If you continue to reinjure your brain over and over again, the consequences of that are a lot more significant.”

Ritter tries to lower the probability of undetected concussions by assigning her athletic trainers one school as their sole responsibility.

“[The athletic trainers] don’t have to try to bounce around to multiple high schools,” Ritter said. “That is the person dedicated to their school, Monday through Friday. They get to know all the coaches, athletes, and the parents.”

When Casey’s symptoms didn’t subside, her family consulted Dr. Debra Balke, a neurologist in Templeton.

Balke told Casey and her family that the velocity of the soccer ball hitting her head, in combination with the post-impact whiplash and neck rotation, jostled Casey’s brain and caused a severe concussion. Balke warned that it could take considerable time for Casey to recover, possibly even a year.

The doctor was right. Weeks and months passed, and Casey’s condition didn’t improve. Not only was she still unable to go to school, let alone be active in any sport, but her symptoms were changing—and not for the better.

“Her symptoms would morph,” said Steve, Casey’s father. “Her sensitivity to light and sounds lasted a couple of months. Then they morphed into headaches, difficulty concentrating, and an inability to read.”

Following that phase, a new set of unpleasant symptoms arrived.

“She became super short of breath and lightheaded,” Nancy said. “We couldn’t walk a block or two without having to sit down. It was like she was 80 years old.”

As Casey’s condition dragged on, the family reached out to various specialists in hopes of getting some new information, techniques—anything that could help Casey along.

“She’s 15, and she can’t socialize, she can’t play sports, can’t go to school,” Nancy said. “It’s really hard to just sit there and wait.”

Doctors agreed that Casey had an issue with her vestibular system, which regulates the body’s balancing of sight, sound, and cognition. But solutions such as vestibular physical therapy, which involved trying to use Casey’s vision to recalibrate her system, didn’t work. The exercises only exacerbated Casey’s symptoms.

“The system’s so out of whack,” Steve said. “It’s not working well together. And every kid, every brain is different. Every concussion’s different. It just takes time, and we’re not patient.”

Medical frontier

In 2006, Dr. Otto Schueckler, a local orthopedist and youth sports team physician, traveled to Pittsburgh to attend a national sports medicine conference.

One presentation in particular caught Schueckler’s attention. Dr. Micky Collins was unveiling an innovative way to manage concussions, called the “imPACT test.”

“Their group really was looking at how do we tell who has a concussion, how bad it is, and when should an athlete be able to return back to sports,” Schueckler said.

The imPACT test is a series of sophisticated computer tasks designed to measure brain function—a way to establish a baseline score to test against in the event of a possible concussion.

If a player scores lower than the baseline test after suffering head trauma, that is evidence the athlete needs more time to recover.

Inspired, Schueckler returned to SLO and talked to Mission Prep High School administrators about the possibility of implementing imPACT testing for the student athletes.

“The administration was really supportive of it,” Schueckler remembered. “But it was sort of like trying to invent the wheel. It was something that no one else was doing.”

After a successful trial, Ritter at San Luis Sports Therapy expanded the imPACT program to all of the SLO high schools she serves. With funding assistance from Sierra Vista hospital, imPACT tests are now mandatory for high school athletes across all sports.

“Before we had an instrument to measure these injured athletes, you are relying on their responses to very standard questions,” Schueckler said. “And [the imPACT] test is an order of magnitude more than that.”

With concussions becoming an increasing concern for youth safety, there’s a renewed sense of urgency to find the next breakthrough in concussion management. Tablet apps, blood tests, and balance tests are all possibilities on the medical frontier to better and more quickly determine if a player has suffered a concussion.

While Ritter welcomes scientifically sound methods, she is cautious when it comes to embracing the next trendy tool.

“Everything that we do in our program is evidence-based and best-practice recommendations,” Ritter said. “There are some products out there that are in the initial testing phase, but we don’t experiment with our kids.”

Through the cracks

By August of last year, Casey’s symptoms were finally subsiding. She passed all the final tests of concussion recovery. Casey was back to normal—sort of. She still struggles with headaches on a daily basis.

The result of Casey’s ordeal? She decided to quit soccer and pick up tennis.

“It’s a smaller, softer ball,” joked her father.

Casey’s parents insist that the decision to switch sports was hers and not theirs.

“If she had chosen to continue with soccer, we would have probably cringed, but supported her,” Steve said. “But Casey’s a smart person. She knew the seriousness of her injury. We’re relieved.”

Even though Casey’s concussion occurred in the most bizarre and unpredictable of ways, it may still have been preventable.

Prior to last year’s winter soccer season (and her February concussion), Casey, like all her teammates, took the baseline imPACT concussion test.

Four months after her concussion, Casey’s baseline test results surfaced.

To everyone’s surprise, Casey had scored poorly on the test, which indicated she may have had a concussion before that fateful PE class.

“We didn’t know her baseline one was messed up until after she had her second one,” her mother, Nancy, said. “They don’t look at [the baseline test score] until after a concussion takes place. They maybe should.”

The mistake underscores the difficulty of tracking and managing concussions in a systematic, error-proof way. When Casey and her athletic trainer believed she was taking a baseline test, she was in reality taking a concussion test.

While coaches, parents, trainers, and doctors do everything in their power to keep kids safe, Casey Lieberman’s and Isaac Lindsey’s stories demonstrate the inevitable few that fall through the cracks, the few who play through a possible concussion when they shouldn’t.

“Secondary impact concussions are what we’re all worried about,” Dr. Schueckler said. “One of the things you worry about as a trainer or a team physician is, what are we missing?”

Some parents may feel like that risk is reason enough to hold their children out of contact sports. Others see it is a calculated gamble, where the benefits from the activity outweigh the probability of harm.

“It’s an individual decision,” said Goossen, the Arroyo Grande High School football coach. “If a parent chose not to have their kid play football, I would absolutely support that decision.

“The goal is to keep it as safe as possible,” he concluded. “That’s our calling. That’s what we need to do.”

Staff Writer Peter Johnson can be reached at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023