[{

"name": "Newsletter Promo",

"id": "NewsletterPromo",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "4",

"component": "15264767",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "0"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

Out of personal necessity, all three men stumbled into starting companies.

Steve Terry just wanted to give his parents in Creston a better internet option than satellite.

Ben Korman needed high-speed broadband on his ranch in Cayucos, and it wasn't available.

Tom Kosta, stuck with slow internet in east Arroyo Grande, found out that a major fiber optic line ran right through nearby Price Canyon, and became determined to connect to it.

Terry, Korman, and Kosta decided to take matters into their own hands—after all, the phone and cable companies weren't doing much—and invent a better option. By utilizing the latest wireless technology and equipment, each local managed to achieve the same successful result: blazing fast internet on their properties, in areas of San Luis Obispo County that have been historically underserved with broadband.

"Necessity is the mother of all inventions," said Korman, who set up his network, now known as Ranch WiFi, about 10 years ago as a young professional out of Cal Poly.

It didn't take long for all three of these home experiments to expand beyond the confines of the creators' properties. Word spread. Friends and neighbors started asking, could they get connected? Sure, why not, the budding entrepreneurs said. It became apparent to them how much reliable, high-speed internet was a need for residents and businesses in rural swaths of SLO County.

"I had people I don't even know coming up my driveway," said Kosta, who started Peak WiFi in South County a few years ago. "What we quickly discovered was—I wanted to solve this problem for my family—there was a huge problem in our community. If you live in one of the townships, you had Charter internet, but everybody outside of town was really suffering."

"There's just been a need everywhere," said Terry, who similarly founded Wilson-Creek Communications in North County in 2010.

Federal and state officials and broadband advocates call this gap in internet services the "digital divide." While the world's economy, education system, and social fabric grows ever-reliant on the internet and access to high-speed connectivity, residents and communities in less populated, rural areas often get left behind.

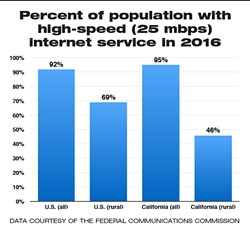

The divide has been identified as a major issue across the U.S. and in California. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) defines high-speed broadband as a connection with a download speed of at least 25 megabits per second (mbps). But according to FCC data from 2016, only 46 percent of rural Californians had access to those speeds, compared to 95 percent of all state residents. Additionally, rural California woefully trails the high-speed connection rate of the overall rural U.S., which is 69 percent.

Wireless startups like the three mentioned above are helping make a dent in the various underserved areas of the Central Coast. Public-private investments in infrastructure have also brought new levels of connectivity to rural school districts and local cities.

But SLO County still has a way to go. In 2016, the Broadband Consortium of the Pacific Coast (BCPC), a tri-county group dedicated to improving "broadband deployment, access, and adoption" in SLO, Santa Barbara, and Ventura counties, gave SLO County a D-minus grade for its internet options. Officials and local experts say a combination of economic, infrastructural, governmental, and cultural factors are at play.

"We're trying to bring awareness to the fact that hey, we're not top-notch. We're barely getting by at some of these speeds," said BCPC member Tim Williams, the CEO of Digital West, an internet service provider to local businesses. "The FCC is shooting for 25 mbps. ... That's a minimum speed. We've got to be shooting for far greater than that."

Infrastructure problem

For students and teachers in Shandon, there's a night and day difference between life in the classroom today versus just months ago. For years, the schools in the small rural community east of Paso Robles couldn't rely on their internet connection to function at all—never mind at decent speeds.

"If you're not sure the internet is going to work every day, you can't put that in your lesson plans," former Shandon Joint-Unified School District Superintendent Teresa Taylor explained to New Times back in 2017.

That all dramatically changed recently, when the school district and SLO County completed a joint project to extend fiber optic cable to the far-flung town.

For the district, partnering with the county was essential. A $70,000 state grant to enhance connectivity in the district couldn't cover the cost of the 1-mile fiber extension. Luckily, the county also needed to upgrade the communications at its fire station and public works facility in Shandon, so they were willing to chip in about twice the value of the grant.

"It was perfect," said Daniel Milei, the chief information officer (CIO) for SLO County. "If you plan ahead, you can spend the money at once."

As a result, the high school and elementary school now both benefit from an excellent internet connection. But the time and cost involved for this relatively small extension offers a sense of the obstacles in the way of expanding broadband networks to existing communities and buildings, Milei said. The extension project took several years to come to fruition, due to the typical complicated planning logistics. It then cost close to a quarter-of-a-million dollars to lay down that single mile of fiber.

Miles and miles south of Shandon in New Cuyama, a tiny agricultural community on the border of SLO and Santa Barbara counties, fiber is not readily within reach. Up until this past April, Cuyama schools operated on "very slow, very low-bandwidth internet," according to school district Superintendent Stephen Bluestein. But thanks to a grant, the district recently built a large radio tower that "beams in" high-speed broadband from the distant Kern County Superintendent of Schools' Office.

"We've been in good shape since then," Bluestein told New Times. "The state testing is all on the computers. It was very hard to do before."

Despite improvements for the schools, the Cuyama community as a whole continues to "suffer from not having a WiFi provider," the district leader said. Only about a quarter of homes have satellite, Bluestein estimated, while some families may try to use Verizon's decent mobile LTE coverage as home internet.

"We certainly know when we're assigning work that [students] may not be able to access any internet connectivity," Bluestein said.

The same assumption could be made back north up in Shandon. While the school sites are now fiber-connected, the homes, businesses, and farms surrounding them did not benefit from that expansion.

"It was brought to the school, and now people are saying, 'Can you bring it to my home?'" Milei said. "That's a private sector issue. That would be an investment challenge for the private sector. That's where the buck stops."

That is where the buck generally stops when it comes to solving the digital divide, Milei noted. It just doesn't make a lot of economic sense for corporations to invest in broadband infrastructure in rural areas, because it usually involves extremely high upfront costs for a small base of customers—a bad combination.

"The whole conversation breaks up when you talk far away, underserved communities. The cost of building that is astronomic," Milei said. "There's no way around it."

Despite the benefits and virtues of achieving broadband equity—economic, educational, civic, health, safety, and otherwise—both the market and the government struggle to deliver it.

"Those are great causes," Milei said, "but nobody wants to pay for it."

Investment and competition

Federal and state agencies are actually willing to pay for some of it, mostly by helping private companies pay for it.

This past October, the FCC announced the results of its Connect America Fund auction, in which broadband firms were awarded a collective $1.5 billion to deliver internet to digitally marginalized areas around the nation. California Internet LP, a Camarillo-based company, was awarded $83 million (one of the top recipients in California) to build networks across the state, including swaths of SLO County between Atascadero and Morro Bay, east of Paso Robles, and near the coast around Cambria. The firm, founded in 2011, claims to be "the fastest growing B2B fixed wireless ISP in Los Angeles," according to a press release from last year.

On the state government level, the Legislature voted last year to renew its California Advanced Services Funds, which will allocate up to $330 million between 2018 and 2022 to support the deployment of "high-quality advanced communications services" statewide. The goal is to give 98 percent of Californians access to broadband by 2022.

But many locals in the internet game like Williams, CEO of Digital West, aren't waiting around for state and federal funding. Over the past several years, Williams has been busy partnering with local governments, like the county and the city of Grover Beach, to make infrastructural advances in the area. On Dec. 7, Digital West and the city of Grover held a ribbon-cutting ceremony for the years-in-the-making completion of fiber optic installation in Grover Beach. It's just one of several public-private partnerships that the longtime SLO company has in store to lay the fiber groundwork for the future, Williams said.

"We're unable to spend literally hundreds of millions [of dollars] like an AT&T or Google, but we can intelligently and entrepreneurially work in partnership with some of our cities and counties and public agencies to try to build this fiber network anyway," Williams told New Times. "There's definitely some growth happening, and we're excited about it. ... It's one of those things where now we're not limited by the medium anymore."

Williams founded Digital West in 1998. He's not only lived through the 20-year evolution of the internet—from dial-up, to DSL, to cable, to fiber—but he's sold those services and tried to innovate with them over time. One thing that Williams appears to have grown tired of over his long career on the Central Coast is settling for a mediocre status quo. With the boundless potential of modern fiber for speed and connectivity, Williams wants to see SLO County, its businesses, and cities seize on every opportunity to deploy it.

"We're the country that really created this medium, this internet, and we're so far behind," Williams said. "Fiber, it's limitless. We can go 100 gigabytes per second if we wanted to."

That sentiment is the thrust behind the PCBC, an organization that convenes the brightest tech minds in SLO, Santa Barbara, and Ventura counties to try to tackle these issues. Williams says one key factor holding up SLO County in terms of broadband progress is a lack of competition in the market.

"We as a society are typically bound to what's been here," he said. "That's been the phone company and the cable company, and the phone company has really kind of dropped out of that market. ... We're really limited to one real choice. If there's only one real choice, there's no incentive for that provider to do any better. ... There's no competition. There's no one to switch to and no incentive to change."

Without saying them by name, Williams is talking about Charter, which has an essential monopoly on cable internet in SLO County (at 90 percent of homes, per the PCBC). AT&T and Verizon are the area's dominant phone service providers, delivering copper wire DSL internet to about 5 percent of county households, at speeds that fail to meet the California Public Utilities Commission's minimum acceptable service level of 6 mbps, according to a 2016 PCBC report. The remaining 5 percent of SLO County homes have no wired broadband option at all.

"When you come down to something as pivotal to our society as the internet, we really don't have choices," Williams said.

From the peaks

Choice—it's what the smaller, fixed wireless companies like Ranch WiFi, Peak WiFi, Wilson-Creek Communications, Outback Internet, Surfnet, Digital Putty, and others finally offered rural SLO County residents stuck with DSL or satellite.

Larry Fluer, who's lived in Adelaida since 1995, had tried every internet service combination imaginable before he became a much-happier Outback Internet customer about a year ago.

"The last service I had was over DSL line, and I got rid of that because I couldn't even download documents from the county website that I had to have for the committee I belong to," Fluer told New Times.

Poor connectivity over the years even hampered Fluer's ability to run his business from home, as Skype video conference calls started becoming an industry norm.

"I wasn't able to hang in on online meetings. Trying to get signal by satellite or any other means, it couldn't be done," he said. "It was a constant battle to do that."

Fluer was certainly not alone in that struggle, which is why this cadre of wireless internet companies has found a niche. What they do is essentially fill the gap in broadband infrastructure by building their own line-of-sight wireless networks from scratch.

Take Kosta, the founder of Peak WiFi in Arroyo Grande. A former IBM employee and self-described innovator, Kosta sources his network from a trans-Pacific fiber optic line running from Asia straight through Price Canyon. He wirelessly relays that fiber signal to a 50-foot antenna behind his house, which then transmits to more than 1,000 connection points throughout the south and central areas of the county.

"It's a miracle that it works," Kosta told New Times. "It's like a symphony."

Kosta built up his network by collaborating with private property owners throughout the region to install "mobile repeaters" at higher elevations. These devices help transmit the signals all around the network. Today, Peak WiFi serves 3,000 to 4,000 customers at homes, wineries, banks, and other businesses from See Canyon, to Huasna, to Edna Valley, its founder said.

Other local wireless providers have garnered similar levels of popularity. Ranch WiFi's network stretches all the way to the Santa Maria Valley. It's also now the internet service provider for Hearst Castle.

"It's city-fast fiber in the country," Korman, Ranch WiFi's founder, said.

Future frontiers

The locally spun wireless networks haven't arrived without some angst. A neighbor to Kosta has voiced opposition to having the Peak WiFi antenna near her property line. Earlier this year, she filed an appeal of a SLO County Planning Department Hearing Officer's decision to allow the antenna to be designated for commercial uses. The Board of Supervisors will hear the appeal at a date uncertain, but 4th District Supervisor Lynn Compton will have to recuse herself. She's a customer of Peak WiFi.

"The tower is very visually inconsistent with neighborhood character, and destroys viewshed and vistas," the neighbor, Trudy Jarratt, told the county hearing officer in February, adding that the business has brought increased truck traffic to the neighborhood.

There are also questions about the potential exposures to radiofrequency (RF) radiation, typically a concern with cell towers. Kosta is quick to point out that the antennas used for Peak WiFi, and other wireless internet networks, are not cell towers, and emit significantly less RF than cell towers.

"The power we use is like ... take your router, put it inside of your wok dish, and put it up in a tree and point it out," Kosta said. "It's the same frequency, it's the same low power. It's like a duck fart in a hurricane."

The dispute has grown tense nonetheless, and Kosta said he's sought advice from the FCC, whose officials responded by asking for his help in crafting language to guide future county ordinances regulating the latest antenna technology.

"The county only has ordinances on the books that are for cell towers," Kosta said. "The tech has outpaced the regulations so we're going to sit down and have a discussion. ... All of our citizens need good internet."

Ultimately, though, the enduring, long-term quality of internet connectivity in the area may only go as far as its infrastructural backbone. Wireless providers need line-of-sight connections to make their network function—which is not always possible with the myriad peaks, valleys, and forests across SLO County and the Central Coast.

Milei, the county's CIO, thinks the only comprehensive solution can come from a larger state or federal investment.

"In my mind, it's just like in the 1950s when they built the freeway system," Milei said. "We need the same thing for the internet. The freeway system took about 20 years to build. It would be the same. You have to start somewhere." Δ

Assistant Editor Peter Johnson can be reached at [email protected].

Latest in News

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023