Diamond in the rough

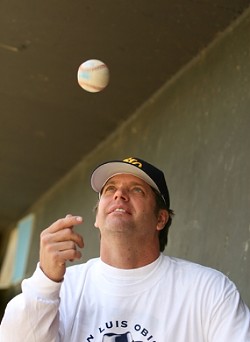

San Luis Blues owner Tim Golden is strange, ungainly and an impossible dreamer, but he might be just what blue-collar ball needs to survive in bourgeois SLO

By Patrick M. Klemz[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

It’s often difficult in this age of crosswalk countdowns, limited peak minutes and seven-second sound bites to find depth. News passes from media outlets, eliciting reaction, sometimes overreaction, and enjoys a brief lifespan in the virtual world before becoming entombed in digital archives. Soon, the cycle renews. A web poll tracks today’s crisis, while tomorrow’s brews and yesterday’s vanishes. But, it’s not all bad. In fact, if there’s one positive trend to spring from our limited attention spans, it’s the rediscovered practice of story telling—breathing life into history. Dates and concepts simply don’t make the cut anymore; nobody cares. Folks learned not so long ago that, in order to capture the modern consciousness, they must tell stories. Some histories seep with personality; others require more effort to escape banality. Our national pastime is most definitely the former.

Â

Â

A sizeable part of the baseball tradition lives in the stories of franchise owners. Whether honored or vilified (often both) these men transformed the game from back-alley preoccupation into the great American spectacle. Much is said of those who made tremendous profits, but countless more incurred equally tremendous losses. Suffice it to say, not all leave the immense footprints of an Albert Goodwill Spalding or George Steinbrenner. Some live in small towns, dwelling among us, struggling to stay competitive in their respective leagues. The average Slobispan might see one such owner enjoying a cold beer at McCarthy’s, or walking around Sinsheimer Park on a spring day. In fact, bet on it. His name is Tim Golden, and he runs the current incarnation of the San Luis Blues, a name he brought back from the dead in 1994. If the moniker sounds only vaguely familiar, hold your horses, there might be another reason. “Turns out we were around before the hockey team,� Golden says of St. Louis’ similarly named NHL franchise. “It’s a good thing too, because ‘San Luis Blues’ has a certain ring to it.�

Â

Of course, San Luis Obispo isn’t the Lou—where Cardinals Baseball remains as essential to the city identity as that awkward bulging monument on the west bank of the Mississippi. Even compared to other Central California club towns, San Luis Obispo is—to put it in the vernacular of the game—bush league, batting ninth. While college and recreational teams have gathered together in the Valley of the Bears for almost for almost as long as the settlement has called itself American, the history of franchise baseball in SLO appears grand at its climax, but otherwise relatively short and riddled with holes. Golden hopes to change that legacy. He talks about fireworks, collegiate All-Americans coming in from the Midwest and grandstand alterations at Sinsheimer Park. “We want to push the fence up and make this area like diamond box seating,� he says, standing in the alley behind home plate. “Rich people like to be separated from the general public.�

Â

But all of Golden’s mammoth baseball dreams require a great deal of work and countless after-hour battles fought in an unassuming office tucked behind a commercial park in the Sinsheimer neighborhood. “I spend so much time here, all three of my girlfriends think I’m cheating on them,� he remarks with a subtle grimace, sitting in the back room of his ramshackle office. The gregarious Golden is rarely caught speechless, and fancies himself rather adept at colloquialisms, but his delivery still hints more of Rodney Dangerfield than Yogi Berra. “I got a ways to go to catch up to Yogi,� he admits.

Â

Almost everything Golden says involves the game in some regard, leaving little reason to believe he launched the team with intentions of entrepreneurial profit. Golden resurrected the team the year of the great baseball strike—proof positive someone didn’t talk to Chuck. In the front office, other signs mark the habitat of a zealous baseball fan: weathered photos and newspaper clippings coat the walls of the bullpen, while Golden’s personal space looks more like the storeroom of a sports card store. A hearty stock of boxes line shelves near the ceiling, marked with names like Donruss, Topps and Upper Deck. Below sit baseball artifacts of a more personal nature—bats and gloves from eras gone by. “Imagine catching a line drive with that,â€? Golden says, tossing over a tattered shortstop’s glove from the 1940s.Â

Â

# A room over, a motley crew of staffers and volunteers manages the day-to-day operations. One man, reportedly of Bonds pedigree, stylishly saunters around in a burnished suit. The rest of the crew works on the mission of the hour—finding host families for the Bluesmen arriving in a few weeks. Seasonal baseball hobbyist and pro linksman Rich Reynolds occupies one desk, and principal investor Joe Vergara—the newest addition to the franchise—sits beside Golden. About a decade ago, Vergara, who recently returned to his native San Luis Obispo to raise his family, cashed in as a co-founder of Jamba Juice. Although involved in the same financial endeavor, Golden and his new partner live a class apart. The quintessential businessman, Vergara rolls around in a Beamer, while Golden drives an arcane automotive eyesore, make and model unknown. One owns; the other rents. “I’m a 44-year-old guy living a college lifestyle,� Golden half-jokes.

Â

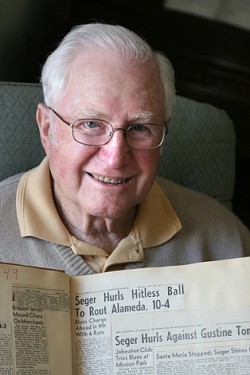

Despite the strong contrast, Golden brought Vergara on board largely because “he gets it.� “It� is the owner’s grandiose ideas about the Blues’ future. “It� is also something, to Golden’s perpetual dismay, many city officials never seemed particularly hip to. So what is it, exactly? According to Golden, it is a renaissance. When Sandy Leguina fielded the very first incarnation of the Blues in 1946, an opening day crowd of 2,000 gathered around the field behind Mission Prep. Old-school Bluesmen report the team averaged about 1,500 a game at a time when the City of San Luis Obispo harbored just 12,000 souls.  Eventually, television took its toll and the town became increasingly gentrified, while nearby cities enjoyed greater growth. In 1983, the Blues finally folded. Golden first concocted the idea of reviving the team in 1987, but was discouraged by the city’s response. Returning seven years later with strengthened resolve, he resurrected the franchise with the concept in mind of restoring the Blues to their former glory. Considering the socio-economic makeup of today’s San Luis Obispo, “pipe dream� might prove an accurate description of this ambitious vision. No doubt certain daunting challenges exist in bringing a blue-collar preoccupation to a white-collar town. But that doesn’t bother Golden—he’s been dealing with naysayers since before the re-founding. To generate interest, he’ll stage just about any spectacle that might attract attention. “It’s Tim’s dog and pony show,� Reynolds quips. Golden responds with a smirk, “Let’s just say I’m not afraid to spend my last nickel.�

Â

However, in visualizing the grandeur of what might be, Golden sometimes forgets what already is. Last summer, the team became so engulfed in an upcoming championship series that some paperwork fell behind, some checks bounced, and the Blues almost went tardy on the rent—all this against a constant backdrop of operational conflicts with the city. “Every year I try to bite off more than I can chew,� Golden says. “We go into things with the best of intentions and it ends up costing us a lot of money.� Golden established promotional beer nights—like those that typified the Blues experience in the Dean Trainer era of the 1970s—wherein beer prices would drop on certain nights and halve when the Blues scored a run. The idea proved popular, but, naturally, it caused a few problems. “Maybe the 25 cent beer thing was a little excessive,� Golden admits with a casual smile.

Â

Above and beyond any individual incidents, bureaucratic battles over everything from banner placement to parking define the recent story of the Blues. These days, it seems, SLO semi-pro ball involves more red tape than ticker tape. Several years ago, Golden saw an opportunity to purchase 1,000 seats from Angel Stadium for roughly $13,000—unfortunately, the city had already put aside $40,000 for seating. “They said ‘we’re going to lose that money in next year’s budget if we don’t spend it,’� Golden says. “Man, I wish I had that problem.� More recent team projects to run afoul of the city include the relocation of a mammoth bull figurine in left field, the introduction of fireworks and the (eventual) construction of team locker rooms. “It’s impossible in this business not to have bigger and better plans,� Vergara says.

Â

The Parks and Recreation Department says it holds the Blues to the same rules as any other group using public park space. In actuality, the team enjoys reduced rent and quite a bit of leeway in payment of fees, according to some city officials. “The city bends over backwards for the Blues,� city council member Christine Mulholland asserts, who believes most city employees see the team as a wholly positive entity. “Of course, it costs us money to maintain the facility.� Before leaping into some of Golden’s more ambitious plans, the folks at SLO-REC and the Joint Use Committee overseeing Sinsheimer Park want to see the team establish good tenancy. “The Blues are a renter of this facility, and we have to treat everyone the same,� facilities supervisor Jim Bremer says. The city claims that Sinsheimer was built for youth baseball, which is why Babe Ruth and Cal Ripken teams use the park free of charge, but not the Blues. Local contractor Steve Burke, whose father, Richard, took a major role in building Sinsheimer Park, disagrees. “I don’t remember hearing anything about Babe Ruth,� Burke says. “They were hoping to get some sort of minor league team in here.�

Â

Although Golden recognizes the city’s good will, he still feels they don’t entirely get it, and he’s not the only one. “The fact that the city gets behind things like the Concert Series and not Blues Baseball doesn’t make a lot of sense,� Reynolds gripes. “They promote the heck out of their own events and not too great a job with everything else.� It’s hardly a new grumbling in San Luis Obispo that prototypically white-collar events become a matter of public priority, while down-home institutions remain marginalized. With Blues Baseball consistently straying on the edge of a knife, it’s a curious speculation what steps the city might take to prevent another extinction. Golden stresses that he needs a partner in the city to keep America’s pastime alive. “We’re not the wine and cheese club,� Golden says. “We like to think keeping the prices low will draw more people, but really it’s the opposite. A lot of people look at a Blues game and think, ‘Eh, it’s a two-dollar event.’�

Â

Of course, for all the kids, working-class families and struggling young professionals, the availability of this “two-dollar event� helps make the summer experience in SLO. After all, this is America. A few thousand dollars a season might seem a reasonable cost to uphold a critical component of the national identity—pennies to the city but a fortune to the Blues, so the argument goes. Yet, Mulholland contends the comparison to the Concert Series—a non-profit entity run by an arm of the city—doesn’t quite stack up. “We have groups all around town doing good works in a variety of ways,� she says. “We can’t subsidize everybody doing good, even if it is the national pastime.� Even Mother’s Tavern owner and councilman Paul Brown, who advertises with the Blues year after year, claims subsidization is no simple matter. “There are times with my business that I feel I’m working for the government,� he empathizes. “Still, the city charges him those fees in exchange for being the official baseball team. If it was free, then why wouldn’t everyone do it?�

Struggles aside, the game must go on. This spring the Blues prepare for a season that has the office buzzing with anticipation. So Golden puts his money down and spins the wheel, hoping, this time, runaway gas prices or some unforeseen fatal faux pas won’t send San Luis baseball spiraling into another dark age. Small victories cause celebration, but the battle continues with no end in sight. For now, it appears that Golden will get his fireworks display, and a fight over catering access has been solved with the donation of a cart by Burke. Tomorrow is another day, however, and a new trial awaits. “It’s like DÈj‡ vu all over again,� Yogi once said. Golden wouldn’t disagree with the great one for a second.

Patrick M. Klemz is a little bit wine and cheese, and a little bit rock n’ roll. Pitch him your comments at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023