Behind closed doors

Prosecutors and victims' advocates battle misconceptions about sexual assault

By Nick Powell[{

"name": "Newsletter Promo",

"id": "NewsletterPromo",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "4",

"component": "15264767",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "0"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

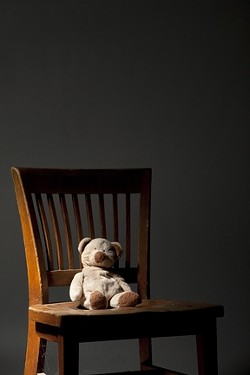

Monsters do exist. They don’t have horns or claws, and they seldom hide under children’s beds or in closets. But they’re very real. More often than not, they wear familiar, happy faces most of the day, giving hugs, support, and the occasional present. They make the rules. They’re big. They should be trusted. Only when other adults are away or asleep do they reveal their other side, taking innocence and leaving deep, emotional scars behind.

The worst thing about monsters, though, is that hardly anyone believes in them. Victims know they’re real, but friends and family too often try to explain away abuse as bad dreams or simple misunderstandings, a response that traps victims in a cycle of isolation and self-blame. Meanwhile, the monster roams free.

In February, the recently merged Sexual Assault Recovery and Prevention (SARP) Center and North County Women’s Shelter and Resource Center launched “Start by Believing,” a month-long public awareness campaign aimed at curbing this common response to rape and molestation. By disseminating pamphlets, speaking at city and county meetings, and spreading the message through social media, organizers hope to encourage an environment where victims feel safer coming forward and confidants believe their stories, because abuse is entirely too real.

Full disclosure

Ronelle Doe looked frightened, nervous, determined on the witness stand in a San Luis Obispo courtroom. Although a court-appointed pseudonym let her keep her identity a secret, the 29-year-old had to face the public, the judge, a jury, a table full of lawyers, and the defendant, her father, in mid January if she wanted to see justice served for the several times she said she woke as a child to find him fondling her inappropriately.

Deputy District Attorney Greg Devitt peppered her with simple questions about a 1997 trip Doe’s family took from their home in Hanford to the Central Coast, and she answered promptly for the most part, telling Devitt who she travelled with (just Mom and Dad), why they were traveling (Mom was getting her tubes tied), and where they stayed (Embassy Suites in San Luis Obispo, in a room arranged with a separate bedroom and sitting area). Her nerves got the better of her when Devitt asked her to crunch the numbers and tell the court her age at the time. Doe answered that she was 11 or 12 years old, but her father’s defense attorney, Melina Benninghoff of Madera, corrected her: She was 13.

The pace of the discussion changed abruptly when Devitt asked why that trip stands out in Doe’s memory.

She swallowed hard and opened her mouth, but the courtroom remained silent for a solid five seconds, a seeming eternity while several jurors shifted uncomfortably in their seats, some unable to look Doe straight in the face, her lips quivering, dark rings around wet eyes.

Finally, with apparent effort, she forced the words out of her mouth.

“That was the first time I can recall waking up to my father with his hands up my shirt fondling my breasts,” she said.

When pressed, she described her feelings in a staccato burst of adjectives: “Devastating. Confusing. Scary.”

Doe said she wanted to flee, but didn’t know where to go in the strange hotel room far away from home. Her mother was in the other room, stirring from the commotion, and Doe said her father told her to say she’d bumped her head, and that’s why she was so upset. She said she was told there was no way her mother would believe the truth, and she worried her mother would kill her father if she did believe it.

“I didn’t know who to tell,” Doe said. “I was scared to tell.”

Years passed before her father touched her again, but he went a step further the next time, Doe testified. Again, Doe quickly answered Devitt’s questions establishing the context, her age, and her living arrangements. She was 17 when it happened. Her parents had divorced a few years prior, and they shared custody equally.

When Devitt asked about a particular night at her father’s house, Doe paused. Her jaw trembled. Then she spoke: “I recall waking up on the couch with pressure on my pubic area. His hands were in my pants touching my vagina. He said he just wanted to get me off.”

Doe said she quickly jumped up, punched her father, and ran to her grandparent’s house nearby; she told her grandma everything, but didn’t get the response she expected.

“Her response was nothing,” Doe said. “She did nothing.”

Her father’s warnings had come true, she said. No one believed her, and she became a pariah in her own family. Again, she described her feelings with a string of adjectives: “Isolated. Awful. Depressed.”

Ten years passed before she felt safe enough to tell anyone else.

In the meantime, she continued to associate with her father. She said he’d promised that the touching would never happen again, so she agreed to travel with him to visit cousins in Monterey when she was 19. Along the way, they stopped in Morro Bay, where Doe and her father shared a two-bed hotel room.

“I was awoken, and the first thing I remember, his penis was around my mouth area, and there was ejaculation all over my face and hair,” she said. “I felt disgusted, scared all over.”

Her father then tossed her the car keys and told her to spend the rest of the night in the truck, Doe said.

At this point in the proceedings, Devitt began asking questions that would prepare Doe and the jury for a cross-examination from the defense. Doe said she didn’t drive away that night because she had only recently gotten her license and was afraid to drive on the highway. She couldn’t say why she continued to trust her father, given his alleged past behavior. She didn’t know why. She just did.

She said she kept the touching secret until 2011 because she had finally moved away from her family and was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Also, her father was living with a new wife and two adolescent stepdaughters, and Doe said she didn’t want them to experience similar abuse.

Devitt asked about a separate civil suit she filed against her father, and Doe said the SARP Center told her that she had a right to compensation.

“I want him to pay for what he did to me,” Doe said. “I’ve suffered. I’ve suffered half my life.”

When Devitt ran out of questions, San Luis Obispo Superior Court Judge Michael Duffy adjourned for a lunch break. An hour and a half later, court reconvened with the announcement that Duffy was allowing Doe’s father to change his plea from not guilty to no contest on all charges: committing a lewd act upon a child, sexual penetration of an unconscious victim with a foreign object, and oral copulation of an unconscious victim. Without explicitly admitting to molesting his daughter, the defendant would be considered guilty in the eyes of the law.

Judge Duffy explained that the no contest pleas allowed the proceedings to end before Doe faced cross-examination, which wouldn’t have been pleasant for anyone. The pleas also ensured that Doe’s father wouldn’t get away scott-free. In exchange, Duffy would grant some degree of leniency. He promised to dole out a maximum sentence of three years in prison, but Doe’s father might get as little as a year in jail or probation, pending the review of a pre-sentencing report to be prepared by the San Luis Obispo County Probation Department. Whichever way Duffy ultimately decides, he explained Doe’s father would be eligible for early release on good behavior.

The defendant said he was willing to accept those conditions in order to put the matter behind him and get back to his family, his wife, and his stepdaughters.

Justice served?

Considering the traumatic nature of the alleged crimes, a three-year sentence may sound offensively lenient. A single act of burglary can land someone behind bars for up to six years, and cocaine smugglers face nine-year prison terms. Don’t child molesters deserve worse?

According to the California Penal Code, they do. Anyone convicted of intercourse, sodomy, or oral copulation with a child younger than 10 is eligible for a life sentence. The same is true of people who assault multiple victims. Several paragraphs of legal code are devoted to sex crimes against children, assigning punishments relative to the type of abuse, the duration, whether or not force or threats were involved, the age of the victim, and the age of the offender. Most come with a minimum sentence of three years in prison.

Had he been convicted by the jury and earned the full wrath of Judge Duffy, Doe’s father could have been put away for up to 12 years.

But that wasn’t likely to happen.

By their very nature, sex crimes are difficult to prosecute. The acts themselves tend to take place behind closed doors and leave little physical evidence. Convincing 12 people that a crime occurred isn’t easy, and the situation is exacerbated by a cultural tendency to blame the victim, a knee-jerk reaction people often use to convince themselves that heinous acts don’t happen, according to prosecutors and victims’ advocates.

In Doe’s case, jurors later admitted that they were skeptical of her claims, even after they heard recordings of her father apologizing for the abuse and watched Doe’s emotionally charged testimony.

After Duffy dismissed them and thanked them for their services, several jurors elected to stay behind and answer questions from the defense. Their opinions no longer carried any weight in that particular case, but Benninghoff could use the opportunity to survey their thoughts and inform future cases.

One of the jurors said she doubted Doe’s testimony and couldn’t understand why the girl would continue to live with her father if he had truly abused her. Others said they were suspicious of the civil suit, and thought the case boiled down to an angry daughter in need of cash.

Doe’s father is due back in court in March for the official sentencing. The delay will give the SLO County Probation Department time to commission and file a pre-sentencing report prepared by a county-approved forensic psychiatrist. Such reports typically include a convict’s family history, community connections, and psychological evaluation—information that can help a judge determine a convict’s risk of reoffending and the danger he or she poses to the community at large. Dr. David Fennel of Atascadero State Hospital said that it’s extremely rare for psychiatrists to recommend probation, but they will in certain cases, like when the perpetrator is the family’s sole breadwinner and he or she is amenable to a strict therapy regimen to ensure that no further abuse occurs.

If the report is damning enough, Duffy could break his promise and decide to sentence Doe’s father to more than three years, but doing so would nullify the no contest pleas and force a re-trial.

Kim Fellows oversees the pre-sentencing reports for the SLO County Probation Department.

“If the jurors were waffling, we as a community are probably lucky he got three years,” Fellows said. “It could have been nothing.”

In 2012, her office processed reports for 23 people, all men charged with crimes that fall under penal code chapter 288, which deals with sex offences against children, the elderly, and the incarcerated. Combing through their court histories revealed long lists of horrible crimes coupled with relatively short prison terms.

Only one of the 23 men was ultimately cleared of all charges, and two are still fighting their cases in court. The remaining 20 all saw their charges reduced when they swapped not guilty pleas for no contest or guilty pleas to lesser counts. None faced complete convictions by a jury.

Their average sentence was 6.8 years, and 10 of the convicted child molesters got three years or less. Seven of the men faced charges that could have put them away for life, but intercourse, sodomy, and oral copulation offences never stuck. Instead, they pled to multiple lewd acts.

The longest sentence was given to a man who got 20 years for two counts of forcible lewd acts on a 7-year-old, plus an enhancement for a prior violent felony. The shortest was 90 days for a lewd act with an adult committed by a caretaker.

Another man was sentenced in 2012 to 270 days in jail after pleading no contest to a lewd act committed in 2008. The offense should have been punishable with three, six, or eight years in prison. In 2005, a lewd act charge was dismissed against the same man when he pled to a lesser count of falsely imprisoning a 6-year-old child on the condition that he’d receive just three years of probation and wouldn’t have to undergo sex offender treatment.

These 23 men hardly account for the entirety of SLO County’s cases involving alleged sex crimes against children.

Three counts each of oral copulation and lewd acts were dropped when one man, who didn’t make the list from the probation department, entered no contest pleas to lesser but related charges of annoying/molesting a child and willful cruelty.

In his trial on Dec. 10, two letters dictated in the confused and stilted syntax of children were read into the court record, describing the “Guess the Candy Game,” in which the children would close their eyes and open their mouths while the accused allegedly placed his penis in their mouths. The mother of the young victims spoke as well.

“I never thought you of all people could do this to my baby girls,” she said. “What you have done will scar them forever. … You deserve to rot in jail for life.”

He got two years.

Three deputy district attorneys handle all of SLO County’s sexual assault, domestic violence, and child abuse cases, and it’s a busy workload. While their coworkers spend two days a week arguing in court and utilize the rest of their time to lay the foundations for their cases, Andrew Baird, Dan Dow, and Greg Devitt are in court every day. When asked, Devitt wouldn’t comment on whether or not the grind impacts his ability to put away sex offenders.

“I just handle the cases in front of me,” Devitt said. “The court hierarchy is what it is.”

He described a whole host of issues that make prosecuting sex crimes especially difficult and said there’s no silver bullet that would make it significantly easier.

He said prosecutors don’t have much say when it comes to sentencing, which is mostly up to the judge, and that he can’t prevent a defendant from admitting guilt or entering no contest pleas to try to court the judge’s favor. The district attorney’s office can use its discretion, however, in choosing whether or not accompanying charges should be dropped, but pressing forward can be a gamble.

If the victim is a child, his or her testimony is often deemed unreliable. Standard pre-trial protocol includes a meeting with a child forensic interviewer to establish where and how the child was touched, but statements made out of court are inadmissible, except in cases where the child’s story shows discrepancy, Devitt said. And then, it only helps the defense.

Frequently, victims keep sexual abuse a secret for years. Since their bodies are the crime scenes, there’s seldom any physical evidence left by the time charges are filed.

“It’s fair to say that the passage of time can impede a successful prosecution,” Devitt said.

Jury bias is another hurdle. For sex crimes, the court sends out roughly double the usual number of jury summons. Many will be dismissed because sex crimes have struck too close to home, Devitt said, and the intimate, traumatic nature of the violation renders impartiality nearly impossible.

The remaining members of the jury pool haven’t been touched at all by sex abuse and often have a hard time accepting that it can happen as often as it does.

“It’s more common than people want to believe,” Devitt said. “Without a doubt.”

Neither Devitt nor District Attorney Spokesperson Jarret Gran disclosed the exact ratio of sexual assault cases that get prosecuted compared to the number of un-pursued complaints. Devitt did say, though, that many get turned down and that he can’t press charges on anything he doesn’t believe he can prove beyond a shadow of a doubt.

“Let’s say you go to trial and the jury acquits. How do you answer the question: ‘Why didn’t they believe me?’” Devitt said. “On an emotional level, it’s very tough. But you have to put emotions aside and deal with the facts of the case.”

‘Start by Believing’

When someone reports that a car is stolen, most people accept it as true. They would never jump to the conclusion that the supposed victim had actually fabricated the story in order to get the neighbor’s son arrested, and they’d seldom blame the car’s owner for parking in the wrong neighborhood. But that’s the kind of logic the public applies to rape victims, according to staff members and volunteers at the SARP Center and North County Women’s Shelter and Resource Center (NCWSRC).

“It puts the onus on victims to make sure they don’t get assaulted, instead of holding rapists accountable for their actions,” Crisis Services Specialist Jane Pomeroy said.

Pomeroy, whose father is a prosecutor, said a discussion with the district attorney about the frustratingly low rate of sex crime prosecution led her and her colleagues at SARP and NCWSRC to bring a national awareness campaign to the local community. The two nonprofit organizations recently announced a merger and will reveal a new, all-inclusive name in July.

Dr. Kim Lonsway lives in San Luis Obispo and volunteers with the SARP Center, but she works for End Violence Against Women International, a nonprofit based in Washington. She co-authored a 2012 report called “The Justice Gap for Sexual Assault Cases: Future Directions for Research and Reform,” which found that just 5 to 20 percent of sexual assaults are reported to the police nationwide. Of those, 0.4 to 5.4 percent are prosecuted and 0.2 to 5.2 result in successful convictions.

“To me the remarkable thing is that people do tell at all,” Lonsway said.

End Violence Against Women International originally conceived the “Start by Believing” campaign, and local statistics and information were incorporated to tailor the program to this community. Assemblyman Katcho Achadjian donated $1,000 for printing materials. French Hospital, Arroyo Grande Community Hospital, Verdin Marketing, and Carmel and Naccasha Attorneys at Law also supported the effort. The Sheriff’s Department and every city police department in San Luis Obispo County (except Arroyo Grande) endorsed the program, which also includes tips for detectives to exercise sensitivity when questioning victims.

Linda Cox of AGPD said the department failed to endorse the program officially only because the request was sent directly to the police chief while he happened to be on vacation.

“There are ways to ask investigative questions without casting blame,” Jesse Torrey, SARP’s interim executive director, said.

According to Torrey and Pomeroy, the first time a victim discloses abuse is crucial. Victims usually tell a friend or family member first, and if they’re met with blame or suspicion, the likelihood that they’ll tell law enforcement decreases dramatically. According to the Rape Abuse and Incest National Network, rapists strike an average of six times, and thwarted disclosures help keep potential re-offenders at large.

“We’re serving victims, not weighing criminality,” Pomeroy said. “Every victim has the right to be believed, and we have the luxury of believing. The public has that luxury, too.”

As the SARP Center’s counseling director, Vicki Pobor facilitated services for 64 clients in 2011, 60 percent of whom had experienced sex abuse as children. Survivors typically struggle to find and maintain healthy relationships and often suffer from stress, eating disorders, and drug and alcohol addictions, Pobor said. Because their abusers are usually family members, many have conflicting emotions when it comes to telling the authorities. As such, the SARP Center doesn’t encourage survivors to take any specific courses of action. Rather, they outline options so that the victim can reclaim control over a situation that once made him or her feel powerless.

“We hope to lift the veil a little bit and create a culture where children can say, ‘This happened to me,’” Pomeroy said.

She said she hopes that as public awareness and acceptance of the reality of sexual assaults increase, so will reporting and prosecution.

Staff Writer Nick Powell can be reached at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023