At home on the range

Cattle, oak trees, wildlife, and history all share the Sinton family's Avenales Ranch

By Kathy Johnston[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

Twenty miles east of San Luis Obispo as the condor flies lies a vast oak-studded ranch, the quintessence of SLO County’s characteristic rural landscape.

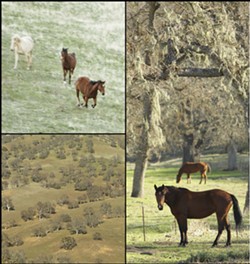

Here in the fresh air of the Avenales Ranch, the gentle mooing of cows and calves is likely to be punctuated by the otherworldly bugling of tule elk or the high-pitched yowl of a mountain lion. These animals see no white-fenced ranchettes, no ridgetop megahomes, no traffic or streetlights.

As historic ranches from Santa Margarita to San Miguel are focusing more on housing development than raising cattle—generating controversy and changing the county’s rural character—how has the 12,000-acre Avenales Ranch retained its wide open spaces for more than a century?

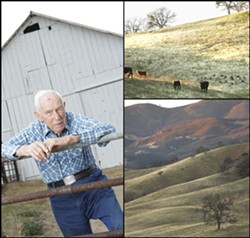

New Times joined 92-year-old rancher Jim Sinton, the spry patriarch of a longtime local ranching family, to explore the historic ranch—a living laboratory for a thriving, sustainable future, with a deep taproot that reaches all the way to downtown SLO and the Sinsheimer Bros. general store of the 1800s.

Jim’s sky-blue eyes peer intently through the open window of his red Explorer Sport Trac as it bounces along one of the dusty roads that crisscross the 15-mile-long ranch. A thin blanket of green is barely visible under the golden grassland, struggling to grow with this year’s low rainfall.

“We’re trying to decide whether to get rid of 70 or 80 steers or not. We don’t have enough grass. You can see if you were grazing out here, you’d have a hard time getting a bite,” he says.

Paying attention to the condition of the grass and the condition of the cattle is key, he explains.

“You’ve got to be thinking ahead. If you leave some of the grass this year, it offers the new grass some protection so it’ll come up sooner next year.”

That may mean selling off some of the steers and heifers, in spite of low cattle prices. Under this management strategy, more grass will be available for the 200 to 300 cow-calf pairs that form the base herd. If there’s not enough grass, the result can be smaller calves and erosion-prone topsoil.

The grass the animals graze today is much different than the grass that once covered these rugged hills and valleys, Jim points out. Introduced in the 1700s by the early Spanish explorers and missionaries, these annual grasses native to Europe quickly crowded out the native perennial bunchgrass. One of the interlopers, wild oats or avena, gave the ranch its name: Avenales, or “place where the wild oats grow,” was the name given to the locale on early maps, Jim explains.

Today, the vast Avenales Ranch is flanked by National Forest, lying west of the La Panza Range and Machesna Mountain Wilderness Area, and north of the Garcia Range and Garcia Wilderness Area. The Sintons supported designation of the wilderness, a spot where California condors have been reintroduced into the wild.

The ranch is also “one of the hotspots in the county” for mountain lions and bears, according to natural resource specialist Bill Tietje of the University of California Cooperative Extension. Around 100 species of birds, including golden eagles, call it home, along with a dozen types of small mammals, bobcats, gray foxes, and a variety of reptiles and amphibians. The mix of wooded areas, chaparral, and grassland the Sintons have maintained supports the wildlife, Tietje says.

Passing through one of the many ranch gates, all sporting easy-opening latches designed to be handled from horseback, Jim stops for a closer look at the condition of some cows and calves gathered near a spring-fed water trough. Satisfied with their health and vigor, he turns his attention to the oak trees that shade the herd.

Many of these oaks have been around far longer than his nine-plus decades. Even the scraggly blue oaks, their normally bluish-gray leaves tinged auburn as they prepare to fall, could have been “alive at the time of Columbus,” he says.

Massive valley oaks and lush live oaks share the vast expanse with blue oaks and a few types of shrub oaks. Unlike other areas of San Luis Obispo County, where ranchers and landowners of the last century chopped down huge numbers of oaks to make charcoal, these trees have been given protection.

“We’ve never cut a living oak,” Jim says. “Something of such age and beauty shouldn’t be cut down and burned in someone’s fireplace.”

It’s this type of attitude that has made the Avenales Ranch a valuable place for scientific study. For nearly 50 years, researchers from the University of California have investigated various aspects of the thriving oak savannah at the ranch and its importance for wildlife and cattle.

Jim, a UC Berkeley alumnus in agricultural economics, helped design and execute an experiment in the early ’60s to test the validity of ranchers’ then-accepted belief that acorns were harmful for cattle to eat. His conclusion: “The presence of oak trees on a grazing range is beneficial.”

He points into the distance at a steep cliff topped by a flat, apparently treeless zone inaccessible to cattle, a place he noticed while riding his horse Annie. Always curious, the nonagenarian, along with ranch manager John Arnold, recently

shimmied and crawled up the nearly vertical cliff to investigate whether oaks are regenerating there in the absence of cattle.

The Sinton family occasionally plays host to a UC Cooperative Extension-sponsored workshop on oak regeneration, when the Avenales Ranch is open to the public for local people to learn more about how to grow oaks.

On a frosty December morning as a chilly north wind rustled across the tops of the twisted oaks, Jim’s son Steve Sinton explained the ranch management strategy to the several dozen people at the outdoor workshop.

Carrying on the family tradition of forward-thinking land care, Steve Sinton received a national Steward of the Land Award from Washington, D.C.-based American Farmland Trust in 2005 in recognition of his leadership in environmental stewardship and conservation.

“The cattle, the wildlife, the trees are all part of the ranch just like we are,” Steve said as workshop participants gathered around him. He emphasized the importance of keeping experienced ranchers on the ranch, saying, “They’ve already made mistakes, and they can pass on their experience to the next generation.”

Steve is interested these days in the long-term survival of the ranch’s magnificent white-trunked sycamore trees lining the riverbed along the headwaters of the Salinas River. Cattle sometimes browse on young sycamore trees, so he’s experimenting with restricting grazing to promote sycamore regeneration.

Developing an attachment to the land is crucial to keeping it in the family, he said. Succession planning is important, so the ranch can be passed on to the next generations without estate taxes breaking it up. Ranching families throughout the county are all learning about succession planning these days, with the SLO County Farm Bureau offering seminars in February and March.

Diversifying, rather than relying strictly on the cattle business, is another key strategy for long-term survival, Steve told the workshop. In addition to government grants available for “good husbandry,” another source of income is a ranch-based hunting club formed more than 20 years ago.

Two-thirds of the club’s 25 local members have been part of the group since its inception, hunting club member Larry Smith said.

“These are local people who care for the land and have come to love it. The landowner has a source of income, the sportsmen have a pleasant experience, and the ranch benefits too,” Smith added.

Hunting club members work to improve wildlife habitat on the ranch by creating and maintaining dozens of watering troughs, complete with special ramps so quail, doves, and other small animals can reach the water for a drink. These sportsmen pay attention to the bird and game populations to keep hunting at a sustainable level, Smith explained at the workshop.

A thriving tule elk population is also a draw for hunting club members. Once nearly extinct in California, the elk were first released at the Avenales Ranch by state Fish and Game officials 25 years ago, thanks to the Sintons’ desire to help the threatened species.

The growing consumer interest in organically raised, grassfed beef offers another possibility for the Sintons to increase income from the ranch, Steve said.

Back on the ranch tour, Jim stops at the old ranch house at lunchtime to talk with ranch manager John Arnold, who’s sitting in the dappled shade out front taking a break from the ranch chores with his daughter Karen and granddaughter Alex Avina, their dogs at their feet.

The men discuss the number of “dry” (not pregnant) cows in the herd, and soon the conversation turns to the difficulty of raising what Jim calls “grassfat” beef during this low-rainfall year. Both ranchers recall the tender, flavorful meat of earlier days when cattle had never seen a feedlot.

Arnold goes inside to grab a package of thick frozen steak given to him by the Nick Ranch next door, which raises certified organic grassfed beef. Offering it to Jim, he warns, “Don’t overcook it. It’s good and tender.”

After a hearty lunch of hefty sandwiches and fresh, tasty salads served by Jim’s daughter Patricia, the tour resumes, and Jim discusses what he’s learned about the long history of the ranch.

“Indians would come through to gather acorns. You can still see a lot of the grinding holes in the sandstone. No burial grounds or evidence of permanent settlements, though. There were still two Indian families living here when the state surveyors came through in 1848, probably hiding from the missions. The missions weren’t always as benevolent as we were taught in grammar school.”

Ever eager to explore, Jim has used the old surveyors’ notes to follow the path the surveyors took across the ranchland, foot by foot. He’s also learned about the ways the native Americans tended the land’s native plants for their own use, and he’s tried eating acorns: “Bland, not particularly exciting, nothing you’d have for Christmas dinner,” he reports.

“That area used to be the hay field, to feed the horses we relied on for transportation. Once we had cars, we didn’t need the hay anymore.

“See that pile of rocks?” he asks, pointing across a dry creek to a clearing. “That was an old homestead. That’s what’s left of his chimney.”

Much of the ranch was originally divided into 160-acre homesteads, offered to willing settlers by the government beginning in the 1850s. Around 65 or 70 homesteads were set up by families or single men, says Jim, who’s fascinated by the ranch’s history.

“The homesteaders built cabins along the creeks, with hand-dug wells. About half had Spanish surnames, and half had European names. I’ve tried to find out more, but there are no records,” he explains.

He’s been to the Monterey Diocese to look at the baptismal records from the SLO Mission, and visited state archives, but information is scarce. No letters, stories, or journals from the homesteaders have been recovered, he says.

One thing he does know: 1898 saw a severe drought, and many homesteaders went broke in the harsh conditions, their cows and sheep starving while their beans and hay crops withered. The homesteaders couldn’t pay their bills to Jim’s grandfather, Bernhard Sinsheimer, who owned the general store at 849 Monterey St. in downtown San Luis Obispo along with his brother Henry.

Jim still has the store’s ledger, which recorded the homesteaders’ purchases of the staple items they needed. Everything was bought on credit till the crops came in and the livestock had fattened up.

Grandfather Sinsheimer ended up with the homesteaders’ land, and aggregated it into the Avenales Ranch. His son, Silas Sinsheimer, changed the family name to Sinton around the time of World War I. Jim Sinton was born on Dec. 13, 1916.

“See that pile of rocks? That was the Vaca homestead. Tomas Vaca was still here when I was a kid, living at a subsistence level. He sold moonshine at the dances in Pozo, till the feds caught him and he sold out to my father.”

Jim recalls that the Garcias, also bootleggers for the Pozo dances, were the last family to sell out to his father. By the 1930s, all the homesteaders were gone, and the Sintons asked the SLO County Board of Supervisors to close the county road through the ranch, once used by horse-and-buggy from the Carrizo and Cuyama. Now, six miles southeast of Pozo, a locked gate marks the beginning of the ranch property.

With a conservation easement in the works to eliminate development rights on the ranch, Jim says he doesn’t foresee a future with mansions on the ridges, although “nowadays in spite of the lack of water, you’d have no difficulty selling this, because everybody wants to own land.”

Leaving the Avenales Ranch cattle, oaks, and wildlife in the capable hands of the ranch manager, Jim heads out through the gate to prepare for his next adventure: He and his wife of 68 years, 88-year-old Norma, are off to Aspen to try out their new skis. ∆

New Times contributor Kathy Johnston may be reached at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023