[{

"name": "Newsletter Promo",

"id": "NewsletterPromo",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "4",

"component": "15264767",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "0"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

In November of 1934, the vegetable fields of South SLO County were teeming with tension.

More than 4,000 field workers, packinghouse workers, and other members of the Filipino Labor Union were on strike. It only took a few days for things to get ugly. It began with a walkout in Santa Barbara County that quickly spread north. Newspaper articles from the period reported that groups of the strikers were overturning trucks hauling lettuce, necessitating law enforcement escorts. A group of packinghouse workers participating in the strike reportedly set fire to sheds where their

The SLO County Sheriff's Office told reporters that they were standing by and ready to respond to reports of violence.

"I'm not afraid of your guns,"

More than eight decades later, on Sept. 4, 2017, a crowd of about 300 people gathered at Strother Park in Arroyo Grande, where the SLO County Democratic Party Central Committee was hosting a fundraiser picnic to celebrate Labor Day. The festive mood was far removed from the tension and violence of the vegetable strike. Photos posted to the committee's Facebook page showed attendees laughing and smiling as they mulled around a grassy patch of the park, eating barbecue and listening to speeches from local labor leaders. In one photo, two women stand in front of a poster featuring the image of Rosie the Riveter. They mimicked the World War II era icon's defiant pose.

The picnic was a chance for the public to see, hear, and learn more about the current state of organized labor in SLO County. At a time when national union membership has declined by an estimated 7 million people since 1983 and more U.S. states eye controversial "right to work laws" that some claim hamstring unions, reminding the public about the contribution of organized labor is more important than ever according to Rosemary Canfield, the committee's chair.

"They are out there fighting for laws at the county, state, and national level that protect workers," Canfield told New Times.

Local labor

Organized labor is in Mark Simonin's blood. Simonin, the business manager for the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 639, has been a union member for 29 years. His father, he says, was also a member of the IBEW. His grandfather was a member of a carpenter's union.

"There's a lot of history there," he said.

Like his father and grandfather, Simonin's career and union membership began in Boston, Massachusetts, a stronghold of organized labor. He eventually moved to San Luis Obispo,

This past spring, Simonin and a few other members showed up to a

Such collective action highlights one of the core tenants of organized labor: The collective power of workers functions as a counterweight to that of the employer.

"Without representation, you can still go to the [business] owner, and we've seen what happens," Simonin said. "You're the complainer. You're the whiner. You'll be the first guy that's going to get cut. It shouldn't be that way."

Simonin isn't the only worker to feel that way. Union membership in the SLO metro area averaged about 22,401 workers between 2012 and 2016, according to estimates from unionstats.com, a database of federal census data collected by Professor Barry Hirsh of Georgia State University and David MacPherson, a professor at Trinity University. That number represents about 25 percent of the local workforce, more than double the average of 11 percent nationally over the same five-year period, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The reason that membership in SLO County's unions is stronger than

"We are really lucky that we are here in California," said Jeremy Goldberg, executive director

Public and private

Goldberg said the unions in SLO County run the gamut in terms of the industries they represent, from construction and trades to agriculture, health care workers, and teachers to government employees.

When it comes to the issue of public versus private sector union membership, Goldberg indicated that the tri-county region is generally in line with the nation—public sector union membership outpaces that of private industries.

According to Hirsh and MacPherson's data, public sector employees like police, teachers, and government employees counted for an average of 63 percent of all union membership in the SLO metro area between 2012 and 2016. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, public sector employees had a union membership rate that was five times higher than the private sector employees nationally in 2016. Two of the industries with the highest rates of union membership were public safety employees like police officers and firefighters, and educators.

The connection between the working conditions of public sector employees and their impact on the community they serve may play a role in the relative strength and influence of public sector unions, including those for teachers and educators, said Donna Kandel, a 15-year-educator and president of the Lucia Mar Unified Teachers Association.

"I think teacher's unions have been successful because they don't just advocate for workers, but they advocate for issues that impact kids," Kandel said.

In addition to negotiating contracts for pay and benefits for the Lucia Mar Unified School District's educators, Kandel's union has also advocated for issues that impact the students they teach, such as opposing overreliance on standardized testing and protecting programs like free and reduced lunch for poor students. Through the union's affiliation with the California Teachers Association and National Education Association, Kandel said the organization could also advocate for the issues and legislation on the state and national levels.

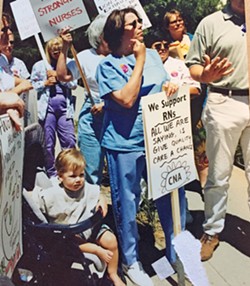

Union workers in the private sector, like nurse Sherri Stoddard, believe that kind of solidarity is a critical aspect of organized labor. Stoddard works at Sierra Vista Regional Medical Center in

"We were able to do that because we did it as a union," Stoddard told New Times.

But organizing a union, especially in the private sector, isn't easy. Workers looking to start a union face a number of challenges, which sometimes include opposition, interference, and even outright intimidation from their employers. Employees most vocal about organizing can risk possible retaliation or even termination should their effort fail.

"When you are starting to organize, there's no protection, really, until you are a union member," Stoddard said.

Charter union fizzles

While Stoddard and the other nurses were successfully able to beat the "union busting" tactics of their employer to form a union in 1996, another group of private sector employees who made a similar effort more than 18 years later

In April of 2014, 48 technicians for the SLO branch of the cable and internet service provider giant Charter Communications successfully petitioned to form a union under the umbrella of IBEW Local 639. According to one Charter employee who was involved in the organizing effort, the technicians wanted to unionize to have more of a say in their working conditions.

"We'd have a voice at the job site," the employee, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation, told New Times. "Without a union, Charter could do whatever they wanted to us."

But it wasn't long after the successful vote that the small group of newly organized employees began to experience what they say was a targeted campaign to undermine and dismantle their union using illegal tactics.

Complaints filed against Charter with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) by the union's members and documents from a federal court case (download PDF) allege that

In signed affidavits to the NLRB (download PDF), one technician said he was called into a manager's office in early 2015, where he heard about plans to go after the newly formed union.

"I don't know where you stand, but I really need your help. We really need to get rid of this thing," the manager, Bill Vedrin, reportedly told the employee.

Another Charter technician wrote that Vedrin asked him what he would do to ensure the dismissal of the union during an interview for a supervisorial position in 2014. Later that same year, the technician alleged that Vedrin chided him for not preventing the union from winning its certification vote.

"He said that if I needed any information to help decertify the union, all I had to [do] is ask him for it," the technician wrote. "He explained that he played an active role in decertifying the union in

In a written declaration to the federal court, Vedrin denied the allegations, stating that an employee had approached him asking about the decertification process, but that he told her he couldn't assist her with such efforts.

"I never asked any employee to assist or otherwise participate in the decertification process," he said.

Vedrin wasn't the only Charter official accused of undermining the union. The affidavit from a senior broadband technician stated that Gary Dressler, the director of human resources, brought up the possibility of wage increases when asked about decertifying the union.

"Dressler said that he legally couldn't promise me anything, but he thought that Charter would do something for us if we decertified," the senior technician wrote.

In his own written statement, Dressler said that the technician brought up the topic; he only responded that union workers would be treated like "any other unrepresented employees" if the union was decertified.

Tensions between the union and Charter came to a head in June 2015, when Charter abruptly announced that it would no longer recognize the union and ceased contract negations.

In a letter to the union, Charter Vice President and General Manager Wally Bakare stated that the company withdrew its recognition after receiving "objective evidence" that the union lost the support of a majority of its members. A decertification petition signed by 27 of the Charter union members was included in the case's documentation as proof of

"Charter believes it must live up to its obligation to honor the employees' voluntary exercises of their legal right to decline union representation," Bakare wrote.

The IBEW filed multiple complaints with the NLRB.

But according to written testimony from IBEW's Simonin, who helped organize the Charter technicians and was a member of their bargaining committee, the damage was already done.

" ... Almost two years after the election, the union has not accomplished anything in the eyes of the [Charter] employees, and is not able to protect employees when they are disciplined or terminated," Simonin wrote. "Some of the employees even blame the union for everything that has happened and

By April and May of 2016, attendance at the Charter technicians' union meetings had dwindled to between four and six people. As of September 2017, Simonin told New Times the IBEW union at Charter had been decertified. It was over.

"I'm really disappointed that it came down to a decertification vote," Simonin said. "I think those employees deserve more."

For the Charter technicians who publicly backed the union, their difficulties may not be over. In his written testimony Simonin raised concerns that they might face retaliation for their roles in trying to organize. The Charter employee and former union member who spoke with New Times expressed similar sentiments, noting that he likely had a "target on his back," though he remained employed with

Despite all the

"Unions are good. They help the workers," he said. "I don't regret anything."

The future of labor

Defeats like those at Charter have become a common occurrence for labor organizers in America. While California and New York remain relative bastions of unionization, union membership across the country has declined more than 20 percent since 1983. In that time, an increasing number of states have passed "right-to-work" laws, which prohibit or curtail the abilities of workers to organize unions and collectively bargain with employers. The law also restricts the ability of established unions to collect dues and membership fees. While those in favor of such laws claim that they offer more freedom and opportunity for workers, organized labor has decried them, stating that they weaken unions, strip workers of their rights, and tip the balance further in favor of large companies that might exploit them.

Those fears are even more present after the 2016 election, which cemented Republican control of both the legislative and executive branches of the U.S. government. Many union members like the CNA's Stoddard feared the passage of a national right-to-work law.

"If this thing passes ... think of all the gains we've made," Stoddard said. "If they are able to take those away, where are we going to be?"

While President Donald Trump himself campaigned as a populist friend of the working class, Tri-Counties Central Labor Council Executive Director Goldberg said that organized labor has little hope he will push for laws or regulations that will help their cause.

"The reality is that there is a long history of this president and his treatment of his workers, contractors that he hired to work on his buildings, but never paid them. There isn't a lot of hope that worker safety and worker protection, or protecting the middle class, are priorities for this administration," Goldberg said.

Still, the contentious presidential election also sparked an increased interest in activism and political organizing, which some unions are seeing as a chance to renew the public's interest in organized labor.

"One of the statements we always make is that sometimes a bad boss can be our best friend," Stoddard said. "Because then you're motivated to get together and do something about it."

Currently, unions across the country have put their people, funds, and organizational might behind a number of issues they feel will benefit union and non-union American workers.

"We need to help people understand that unions aren't some special interest group out there just for ourselves," Goldberg said. "

For many of the union members that spoke with New Times, advocating for issues like health care, fair wages, and others represents a chance for organized labor to remind Americans about the gains made in the past, when unions fought and successfully advocated for the 40-hour work week, minimum wage, workplace safety regulations, and ending child labor.

"We are working really hard to educate our members and the public about the benefits of our unions," educator and Lucia Mar Unified Teachers Association President Kandel said. "Sometimes people take for granted what they have because of unions, and we need to make sure people are more conscious about what unions have done for them."

That burden of that effort will likely fall squarely on the shoulders unions members themselves. In the end, the power and strength of organized labor, in SLO County and beyond, rests in the hands of those most willing to take action and be vocal and visible.

"It's like joining a gym," Kandel said. "You don't get fit just by signing up." Δ

Staff Writer Chris McGuinness can be reached at [email protected], or on Twitter at @CWMcGuinness.

Latest in News

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023