FYI: The dictionary defines "blight" as the state or result of being deteriorated or ruined.

Rethinking Redevelopment

The Blight-Fighting Program Is Often Used to Subsidize Private Developments and May Soon Be a Tool in the Fight Against an Adult Business

BY STEVEN T. JONES

Corporate welfare or a stimulation of private investment? An aging downtown or urban blight? Free money or taxpayer dollars? A valuable tool for turning around problem areas or a $1.5 billion annual tax grab?

The concept of redevelopment in California, and in San Luis Obispo County, hovers between two opposing perceptions. It can either be a taxpayer subsidy of private development or the stimulus needed to encourage the private sector to take on projects it otherwise wouldn't. Sometimes it's both.

Take the Prime Outlet Center as an example. In the early ’90s, the Pismo Beach Redevelopment Agency paid $732,000 for site and road work that normally would have been the responsibility of developer Michael Towbes.

Those public funds were used to help turn a dilapidated old shopping center into today's gleaming economic draw. City manager Mike Fuson said public investment was needed to make the project happen and, given the economic lull of the time, he is probably right. It might not have happened right then if not for redevelopment.

But would such a prime piece of Pismo Beach real estate–located along a major freeway, at a spot that has more potential customers driving by than any other point in the county–still have been vacant today? With today's hot economy, would it still take a taxpayer subsidy of three-quarters of a million dollars to interest a developer?

"You're right. On this freeway location, sooner or later, the demand would have been there," Fuson acknowledged, although he said the project has been nothing but positive for the city.

This is one of many redevelopment projects in San Luis Obispo County that have turned around deteriorating areas and, in the process, increased the sales tax revenue headed into city coffers.

The reality of redevelopment is that the contrasting perceptions presented in the first paragraph aren't opposing ideas at all but ones that coexist, often within a single project. The scales tilt one way or the other depending on your perspective.

Far from the magical panacea many local officials make it out to be, redevelopment is a complicated and multifaceted program that raises interesting questions about when it's appropriate for the taxpayers to subsidize private businesses.

Fighting ‘Blight’

Five of our county's seven cities have formed redevelopment agencies, making us roughly proportional to the 367 out of 475 California cities that also have redevelopment agencies.

Pismo Beach and Paso Robles formed redevelopment agencies back in the ’80s, while the cities of Atascadero, Grover Beach, and Arroyo Grande created redevelopment agencies in the just the last couple of years. The county is also now looking at redevelopment.

The concept of redevelopment is a simple one, even if the details of the process can get a little complicated. A city or county starts the process of forming a redevelopment agency by declaring a specific area to be "blighted."

The idea is that deteriorating urban areas pose an economic and social danger to a community–creating crime, driving away businesses, diminishing the quality of life, spiraling into further decay–so government needs to intervene, because the private sector otherwise won't help.

"The high risk and fear of the loss of an economic investment prevents private enterprise from reversing the downward trend in a blighted area without government assistance," according to a primer by the California Redevelopment Association, whose membership includes 324 agencies and 264 private companies.

Once a redevelopment agency is formed, then all subsequent increases in property tax revenues from the blighted redevelopment area go to the agency. This is known as the "tax increment."

For example, the $784,000 in revenues the Paso Robles Redevelopment Agency received this year represents the approximate property tax increase in the redevelopment area since the agency was formed in 1987, minus a "pass through" to other agencies.

Normally, property taxes from within a city are split among the city, county, school district, and any other special districts serving that area. Once a redevelopment district is formed, it receives the lion’s share–about 70 percent–of any property tax increases, leaving the other agencies to divide the remainder.

Statewide, 8 percent of all property tax revenues–$1.5 billion in 1999–go to redevelopment agencies. The agencies use that money to execute their redevelopment plans: paying for infrastructure work, property acquisition, bond repayments, and development subsidies.

While such a system seems to take money away from schools and other districts, in reality much of that diversion gets backfilled by other state programs, like the Education Revenue Augmentation Fund for school districts. So what seems like free money to redevelopment districts often comes indirectly from state coffers.

But in the days before redevelopment and school financing laws were changed in the mid-’90s, redevelopment really did take money from schools, counties, and other agencies.

So forming a redevelopment agency usually involved negotiating tax "pass throughs," or payoffs to affected agencies to offset the loss and keep them from challenging an agency's formation in court.

Often, lawsuits got filed anyway, as Grover Beach officials learned when they tried to form a sprawling redevelopment district in 1993, only to be sued by the county.

Change of Heart

In March, the Board of Supervisors authorized funding for a study looking at whether the county should form redevelopment agencies in communities like Oceano, Avila Beach, Nipomo, and Los Osos.

That move toward redevelopment was triggered by the arrival of the county's new planning director, Victor Hollanda, a redevelopment true believer who was hired partly for his economic development expertise.

"He believes we may be missing an opportunity to help some of our communities do things that need to be done," said Dana Lilley, who heads the Planning Department's Housing and Economic Development Division and is currently writing the parameters for the study, which should be completed by year's end.

It’s ironic that the county is now pursuing redevelopment after–just seven years ago in its lawsuit against Grover Beach–attorneys for the county slammed redevelopment as little more than a scheme to give public funds to private developers.

"By this action the county of San Luis Obispo and several county taxing agencies seek to set aside an unlawful redevelopment plan which would divert tens of millions of dollars of their respective property tax revenues in order to subsidize developers in the city of Grover Beach," read the suit.

It pointed out that Grover's redevelopment district covered 650 acres, encompassing 40 percent of the city's residential area and nearly all of its commercial and industrial land. Redevelopment districts are usually created as large as possible in order to capture the most possible revenue.

"Grover Beach is a suburban community with a growing economy, and neither the project area nor the balance of the city is characterized by the kinds of chronic and pervasive blighted conditions which are a prerequisite to the use of drastic redevelopment powers," wrote the county, making an argument that could very well be used against its current efforts.

Aside from loose state definitions about what blight is, cities are free to fashion their districts any way they choose. The formation of a district isn't subject to state approval or oversight.

Grover Beach's attorney pushed for a change of venue over county objections that "Defendants seek to have this action removed to a distant venue far from the watchful eyes of the affected public and the press who serve them."

The motion was granted and the case was moved to Santa Barbara County, where a judge eventually ruled that the district was invalidated because of procedural errors in the city's adoption process.

"After all this litigation was ended, we settled with Grover Beach for a much smaller area," said assistant county counsel Jac Crawford.

Everyone's Doing It

The Grover Beach Improvement Project now covers 185 acres: about 12 percent of the city, 679 parcels on the west side. Like Arroyo Grande and Atascadero, it is a new district without much funding yet but with big plans for the future.

"We're really in the initial first years of the redevelopment agency," said Grover city manager Tom Odom. "But we're lucky enough to have projects in the redevelopment area that we haven't had to participate in any way."

Given that redevelopment districts are intended to spur development in areas that the private sector wouldn't otherwise touch, the fact that development is naturally occurring seems to be an argument against the need for redevelopment.

The county lawsuit made that same point in the mid-’90s: "In fact, the improvement area is not blighted and is experiencing growth and new development without redevelopment assistance."

But Grover's finance director, Brian Johnson, said that just because the strong economy has stimulated growth in the redevelopment area, that doesn't mean the district isn't needed, especially once the economy cools.

"It's the same argument with economic development, that things happen naturally," Johnson said. "And when the economy is going good, then the private sector will take care of it."

The goals for Grover Beach that require a redevelopment agency include the need to consolidate small commercial parcels into larger lots, renovating the city's affordable housing stock, increasing the city's sales tax base, and cosmetic improvements in aging neighborhoods.

"Redevelopment agencies are tools to enhance and guide redevelopment activities," Johnson said.

Arroyo Grande's redevelopment agency is in the process of a million-dollar bond issue, money that will initially be used to facilitate projects that generate sales tax or increase the property tax base, thus funneling more money into the redevelopment agency for later improvements.

Arroyo Grande has divided its district into four "principal improvement zones"–Grand Avenue, the Village District, Traffic Way, and El Camino Real–and identified five key intersections and blocks as having strong redevelopment potential.

Although newer than Grover Beach or Arroyo Grande, so new that it has yet to receive its first infusion of property tax funding, Atascadero's redevelopment agency has already subsidized its first project.

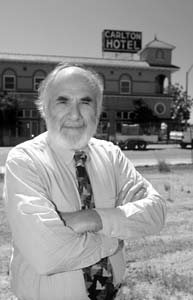

The city of Atascadero has long tried to use government funds to help a developer restore the Carlton Hotel, which was once, and may be again, the economic centerpiece of downtown.

The city even got fined in the early ’90s for improperly turning over federal Community Development Block Grant funds to a would-be developer who promised to restore the Carlton but instead skipped town with the cash.

The ink was barely dry on Atascadero's formation of a redevelopment district earlier this year when city officials announced an owner participation agreement with a partnership headed by wealthy developer/publisher David Weyrich to restore the Carlton.

The agreement calls for the redevelopment district to later reimburse Weyrich for about $115,000 in permit fees and construction costs for sidewalk improvements and completion of a public parking lot.

Such costs are usually borne by developers, but Paul Saldaña, Atascadero's director of community and economic development, said the city was already committed to doing the sidewalk and parking lot improvements, arguing that the city's direct subsidy for the Carlton was only the $9,600 in waived permit fees.

"The city views it as more of an investment," Saldaña said, "to have a project redeveloped that otherwise wouldn't be."

Even if the city subsidy was the full $115,000, Saldaña pointed out that there is nothing wrong or inappropriate about subsidizing the development of projects deemed to be in the public interest.

"The redevelopment power the state has provided was done to allow cities to participate in public-private partnerships. That's clear," said Saldaña. "This plan and the effort we're doing exceeds both the intent and spirit of the redevelopment law."

Power and Responsibilities

Atascadero City Councilman George Luna was the swing vote needed to approve redevelopment in Atascadero, his support becoming essential after two other council members who owned property downtown had to recuse themselves because of the conflicts of interest.

A slow-growth advocate, Luna forced several key changes to Atascadero's ambitious redevelopment plans, including scaling back the project area and requiring a unanimous vote for project subsidies.

While concerned that the district could be used to subsidize development along El Camino Real, Luna said he ultimately supported redevelopment for its power to rehabilitate housing and restore the downtown area around the Carlton Hotel.

Part of that restoration that excites Luna and other city officials is what could be a new power to oust Diamond Adult World, the sex shop that has drawn fierce opposition in Atascadero but which has a First Amendment right to be treated like any other business.

After Diamond opened in the mid-’90s, the Atascadero City Council approved an ordinance calling for adult businesses to be located outside the downtown core. But with Diamond already there, the city had no power to oust it.

Yet redevelopment agencies have far more sweeping powers to acquire properties that don't conform with city plans through condemnation and eminent domain. Even though Diamond's freshly renovated building is among the least blighted in the downtown–and the only building downtown to have completed its seismic retrofit–city officials want to seize it in the name of redevelopment.

"Redevelopment agencies don't have the problem with the First Amendment," Luna said. "We can condemn that property, move him, and get someone else in there."

While getting rid of Diamond may not prove to be quite that easy, Luna's point illustrates just how powerful redevelopment agencies are under state law.

Redevelopment agencies can force property owners in the redevelopment zone to sell their properties at current market value and can even seize the property of recalcitrant owners. Tenants can be evicted to make room for new uses of the property.

Often redevelopment agencies buy small parcels of land in order to consolidate them and turn them into larger parcels, which are then sold or given to developers. Such consolidations are a major goal in Grover Beach.

Unlike other governmental bodies, redevelopment agencies are also free to hand-pick developers for favored projects, a power that has opened up redevelopment agencies to charges of cronyism.

While state law gives redevelopment districts tremendous powers, they are also given a few responsibilities, such as mandating the creation of more affordable housing in cities that use redevelopment.

In fact, redevelopment agencies are required to set aside 20 percent of all revenue for affordable housing needs. Yet many cities are loathe to use those funds to actually create housing for poor people, which can be politically difficult, especially in affluent communities.

State figures show that annual spending on housing by redevelopment agencies constitutes just 2 percent of their expenditures, compared to the 46 percent the agencies spend on debt service, 19 percent on construction, and 13 percent on administration.

None of SLO County’s five redevelopment agencies have done much to increase their affordable housing stock. Instead, much of the affordable housing money that has been set aside is simply sitting in funds, waiting for the political decisions that will help turn the money into housing.

In Pismo Beach, where residential development in recent years has included almost nothing but expensive homes, the redevelopment agency's affordable housing fund has reached $600,000.

"It's been accumulating with virtually no expenditures," Fuson said. "The costs are so high here that affordable housing is going to be difficult."

Paso Robles has made the only significant affordable housing expenditure–giving a $130,000 subsidy to a senior housing project–and has used half of its affordable housing set-asides to pay administrative costs for its housing program.

But even after that, Paso still has nearly $400,000 sitting in its affordable housing fund, waiting for a worthy, politically acceptable project.

"I suspect our next focus will be on housing," said Bob Lata, the community development director for Paso Robles.

The Critics

The county may have reversed its opposition to the concept of redevelopment, but many other public officials remain unswerving in their condemnation of the concept.

One of the leading critics of redevelopment is a group called Municipal Officials for Redevelopment Reform, or MORR, whose board is comprised of sitting city council members and other civic leaders from around the state.

In April, MORR released a report called "Redevelopment: The Unknown Government," in which it criticizes the redevelopment process as an undemocratic giveaway to big business that enriches developers, consultants, and bond brokers at the expense of taxpayers.

"It's all about subsidizing retail. It has nothing to do with helping poor people," said Chris Norby, a Fullerton city councilman who serves as MORR's statewide director. "It's just shameless."

Redevelopment agencies are usually created because it seems like free money to address local needs. But the reality is that money isn't free, coming from the same taxpayer funds that provide essential services.

"The tax increment is a kind of shell game. They get the property tax, but it comes from somewhere," Norby said. "It's a zero sum game."

That "somewhere," according to Michael Dardia, is usually from the coffers of state and county governments, which he found to be the big losers in the 1998 report, "Subsidizing Redevelopment in California," that he wrote for the Public Policy Institute of California.

"The counties and state end up picking up the tab for redevelopment," Dardia said.

Norby said another loser ends up being small businesses, which often get hurt by the influx of major retailers that are favored by city governments because of the sales tax they generate.

"The mom-and-pops get squeezed out by the big developers favored by redevelopment agencies," Norby said. "The big guys are rewarded, and the little guys get dispossessed."

Redevelopment plans also usually generate a cadre of critics in each city, people who recognize the downside of redevelopment's big promises.

"It's turned into a real can of worms for the taxpayer," said Atascadero resident John McGoff, a vocal critic of Atascadero's original redevelopment plans. "The taxpayer thinks this is found money, but it isn't. The tax increment comes out of money that would be available for other things."

Yet even so, most city officials focus on the positive potential of redevelopment to help improve their communities.

"The whole concept of the public-private partnership is the key," said Saldaña. "It's the Main Street Program model. It provides opportunities for agencies to enter into public-private partnerships to stimulate the redevelopment."

To critics, however, "public-private partnerships" is just a euphemism for government subsidies of big business.

"Instead of corporate welfare, they want to call it joint public-private partnerships," McGoff said. "But it's the same thing."

Beyond the philosophical concerns about corporate welfare, redevelopment is controversial because it requires cities to label certain neighborhoods as "blighted," which carries emotional baggage and can lower property values.

"Redevelopment is like a pejorative term that has been controversial from the beginning. People say, ‘What do you mean it's blighted?’ " Fuson said. "It's historically been controversial, and it remains so here too."

San Luis Obispo looked at creating a redevelopment zone, particularly as a means of renovating aging sections of mid-Higuera and South Higuera Street, but decided against it last year.

"In order for this city to generate a measurable amount of redevelopment money, we would have had to create a redevelopment area all over town, with all the fears and concerns that creates," said Ken Hampian, assistant city administrative officer.

Assessing Paso

Few would question the view that downtown Paso Robles has undergone a dramatic transformation since that city formed a redevelopment agency in 1987, the oldest and largest redevelopment agency in the county.

Redevelopment funds were used to renovate City Park and build new sidewalks in the area, creating a more inviting commercial district. They were also used to help renovate the city government center and library and to purchase an interim City Hall site.

Few would dispute that these are legitimate uses of public funds, even if city officials say the reason for keeping City Hall downtown was because the business community wanted it there to help revitalize the downtown economy.

Yet such public improvements were only the beginning, consuming only a portion of the $4 million in tax increment revenues–plus a $3.6 million bond issue and $4.4 million loan from the city's water fund–that the redevelopment district has taken in during its lifetime. Most of that money has gone directly to subsidizing business.

The most dramatic example was the redevelopment agency's 1993 owner participation agreement with the developers of the Woodland Plaza II shopping center, which is anchored by a Wal-Mart.

To facilitate the project, the redevelopment agency agreed to do $1.6 million in site improvements normally done by developers and another $3.6 million in road improvements, primarily for expanding Niblick Bridge, part of which would usually be paid for by developers as part of their project mitigation.

To help with the development of Park Cinemas downtown, the redevelopment agency paid for $184,752 in site improvements needed by the project.

There have also been more generalized business community subsidies. Between 1988 and 1998, the agency handed over about $640,000 to the Main Street Program, a nonprofit organization that serves the local business community and does economic development work.

In addition, almost 50 downtown businesses have taken advantage of the district's facade improvement program, which gives interest-free, deferred-payment loans to businesses for facade improvements, at a cost to the district of $121,200.

Yet for all the work and spending by the redevelopment agency, city officials say redevelopment has been only partly responsible for the rejuvenation of downtown, much of which was triggered simply by a strong economy and a pro-business City Council.

"Most of the development in the redevelopment district has occurred on its own," said Paso Robles treasurer Mike Compton.

Which, again, begs the question of whether California taxpayers should be subsidizing development in Paso Robles or whether that money could have been better spent on schools, police, or social services.

Lata said the district's expenditures have done nothing but help Paso Robles and its residents: revitalizing the downtown and improving both shopping opportunities and the city's tax base, which in turn makes more money available for city services.

"The facade improvements have really been a catalyst for more people coming downtown," Lata said. "If you look at where the downtown was 15 years ago, there has been a dramatic improvement."

With the Park Cinemas project, Lata said, the subsidy was needed to prevent the developer from building on the city's fringes, where costs would have been less.

"We would have seen a theater here, but they probably wouldn't be downtown and wouldn't be part of the revitalization of downtown," Lata said. "It's important to look for the catalysts that will cause other things to happen."

As to subsidies for both the Wal-Mart project and Main Street Program, Lata said those were consistent with political decisions made by the City Council to turn Paso Robles into the region's economic hub.

While city officials felt they needed the sales tax from a regional mall outside the downtown core, they also recognized that could be a drain on downtown businesses and used the redevelopment agency to offset that impact.

"We knew it would have an impact downtown and we wanted to help with that," Lata said. "It was a way of making sure downtown remained a viable and vital part of the community."

Playing the Game

Much of the criticism of redevelopment is the same as that of economic development in general. With sales tax being the biggest source of city revenue, cities compete with one another for businesses that generate a lot of sales tax.

To gain advantage in that competition, many cities offer to subsidize favored projects by waiving permit fees, doing infrastructure work, sponsoring bonds, donating or consolidating land, or even offering direct payments.

And when cities use redevelopment districts to gain a competitive advantage in the battle over big sales tax generators, critics say that is an inappropriate use of public funds and the redevelopment concept.

"The purpose of this is to eliminate blight, not build Wal-Marts, but it isn't doing that," Norby said. "What cities wind up doing is pirating each other’s sales tax. It is corporate welfare at its worst."

In their haste to attract big-box stores and other large retailers, Norby said city officials often lose sight of the real needs of their constituents, which include quality of life concerns that go beyond shopping.

"Is that really what we want, people racking up more credit card debt so cities can get sales tax dollars?" said Norby.

Yet city officials justify incentives and giveaways to large retailers by pointing out they end up paying for themselves in increased sales tax revenue.

"I don't hear anybody complaining today about the sales tax from the Outlet Center or that shopping opportunity," said Fuson of Pismo Beach. "By and large, it's been a positive for this community."

It's tough to argue with results. Given that cities often need big sales tax generators just to fund basic services, corporate welfare on the local level sometimes just makes economic sense. That's why critics want major changes in the system.

In "Redevelopment: The Unknown Government," Norby and other MORR members propose fundamental changes in how cities are funded as a means of stemming the scramble for retail: "A more far-reaching reform would be to replace the point-of-sale [with] a per-capita tax disbursement. This would create a more equitable distribution of public revenue and completely end costly competition over major retailers."

As for redevelopment, MORR is urging the state to step in, seize redevelopment assets, and restore the diverted property taxes to schools, counties, and special districts.

"The original rationale of redevelopment was to eliminate blight. It was a temporary fix for a temporary problem. Redevelopment agencies were never supposed to horde an ever-growing slice of property taxes indefinitely," MORR wrote. "Let them share it now." Æ

This is the last cover story staff writer Steven T. Jones will write for New Times before he starts work at the Sacramento News & Review next month. His last day is June 23, but he will remain in the pages of New Times with a regular column on capital politics and their impacts on SLO County.