Nearly All Chumash Aren’t Recognized by the Federal Government and Won’t Share in Those Gambling Profits

BY TERRI DUNIVANT

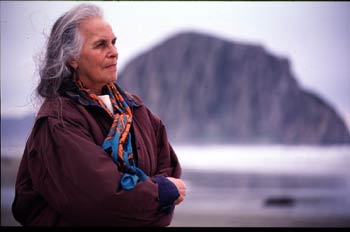

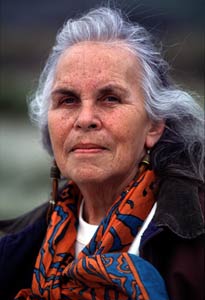

For most SLO County residents, Pilulaw Khus has long been the voice and face of the Chumash people (certainly until the recent spate of pro-gambling commercials).

She’s been active in pressing for the sanctity of Chumash burial and religious sites. She has presided over sunrise services at Earth Day events. She has spoken about the history and philosophy of her people.

Just one problem: Khus isn’t Chumash.

At least that’s what the federal government says.

Khus is one of some 5,000 people of Chumash ancestry who are denied recognition because, in part, their ancestors refused to be put on the reservation when the white people came to California.

This is the story of how that division came to be and the ongoing struggle for 98 percent of Chumash people to gain recognition, a homeland, and a say in the gambling proceeds that could soon skyrocket if voters on Tuesday approve full casino gambling on the reservation.

How It All Began

According to Chumash legend, "There were no people in the world when the Earth Mother Hutash created the first people on the island called Limuw from the seeds of a magic plant. Hutash was married to Sky Snake, the Milky Way, who sent fire to the people in a bolt of lightening.

"Life was good for the Michumash, and after many generations Limuw became crowded and noisy. This kept Hutash awake at night so she decided to send most of the island people to the mainland, where no one lived. She made a rainbow and told them to go to the other side, where there was plenty of land and everything they needed.

crowded and noisy. This kept Hutash awake at night so she decided to send most of the island people to the mainland, where no one lived. She made a rainbow and told them to go to the other side, where there was plenty of land and everything they needed.

"On the long walk over the rainbow bridge some of the people got dizzy and fell off, down through the swirling fog into the ocean. Hutash didn't want her people to drown, so she turned them into dolphins."

Those who made it across the rainbow bridge spread out along the coast, occupying a territory of some 7,000 square miles and establishing permanent settlements between Tissimasu, north of what is now called San Simeon, and Humaliawo (Malibu). Some of their villages lie buried beneath cities that have adopted their names: Pismu’, Nipumu’, Lompo’.

Before the European invasion, about 15,000 Chumash lived throughout this vast region. Some archaeologists say the evidence confirms at least 15,000 years of continual occupation; others estimate only 3,000. If you ask Chumash elder and Bear Clan spiritual leader Pilulaw Khus, she will say, "We have always been here."

The Chumash were first contacted by Europeans in 1542, when Portuguese navigator Joao Rodrigues Cabrillo, after taking part in the conquest of the Aztecs, sailed past the Central Coast on an expedition funded by Spain.

More than 200 years later, Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa was founded when Father Junipero Serra hung a bell from a sycamore tree near a somewhat obscure Chumash village called Tixlini. It was the fifth in a chain of 21 Spanish missions established in California to make the Indians into Catholic subjects of the Spanish empire and secure the resources of the land.

Serra was a member of the Spanish Inquisition, struggling for power with the Mexican governor at the time, Felipe de Neve, who wrote that, "The unhappy treatment which the Franciscans give the Indians renders the Indian condition worse than slaves. The fathers aim to be independent and sovereign over Indians and their wealth."

According to John Anderson, an ethnohistorian who's been involved with local Indian issues for more than two decades, the Chumash were once the largest cultural group among the Western tribes. During the 60-year period of mission dominance, some 53,000 adults were baptized and 37,000 were buried, a mortality rate of nearly 70 percent.

Mission rule was only the beginning, however, of what many Indian scholars and native peoples call the California Indian Holocaust.

In 1810 Mexico went to war with Spain, winning independence in 1822. The missions were secularized and sold, with San Luis Obispo going for about $500. The rest of the territory was divided into huge land grants deeded primarily to Mexican families. Thus the Chumash officially became outcasts in their own land. Squatters with no rights.

After the United States won California from Mexico in 1848, the first governor proposed a war of extermination against all California Indians. Roving bands of state militia were commissioned to hunt native people and capture or kill them wherever they were found. Account after account is given in letters from Indian agents, newspapers, and official war records detailing the brutality of the settlers and miners and the death squads, who directly and indirectly killed an estimated 80,000 natives over the next few years.

California was a war zone, the scene of one of the most successful "ethnic cleansings" in history. Within the span of a single long lifetime, 90 percent of California’s native people were dead.

Those who survived were enslaved. About 10,000 California Indians were sold between 1850 and 1863–legally. Under "An Act for the Government and Protection of Indians," natives of all ages could be indentured to any white citizen for up to 25 years. According to a Humboldt Times article published in 1855, "A large number of (Indian) children have been brought down and sold in the agricultural counties. They bring from $50 to $200 each."

Under pressure from church leaders, human rights groups, and the press, the United States began establishing reservations, usually in areas that were deemed unfit for white habitation. Several Chumash bands fled inland, hiding at the southern end of the Central Valley and surrounding foothills.

The First and Only Chumash Reservation

Located about 30 miles north of Santa Barbara and 10 miles inland is the 128-acre Santa Ynez Reservation. It’s the only reservation on the Central Coast, the only tribal land set aside for Chumash. About 5,000 people claim Chumash ancestry, but fewer than 100 are members of the Santa Ynez Mission Band, and only members over 18 are allowed to vote on tribal business.

In his book "The Chumash," local archeologist Robert Gibson writes that the California Native American Heritage Commission recognizes the Indian heritage of members of several regional Indian councils as well as members of the Santa Ynez Band, but the federal government only recognizes those who are enrolled as members of the Santa Ynez Band.

If you are Native American, federal recognition or the lack of it determines where, and often how, you will live.

Michael Khus-Zarate grew up in San Luis Obispo. He’s part of the Coastal Band of Chumash Indians, a 900-member nonprofit "urban Indian organization" that is one of many groups whose members are recognized by the state but not the federal government.

Khus-Zarate, a former Marine Corps captain who graduated from Stanford with a master’s degree in education, currently teaches history at a high school in Clovis, unable so far to find a teaching position in this area. He is also a member of the Advisory Council on California Indian Policy, an organization funded by Congress to study federally recognized and unrecognized California Indians.

"Being recognized means you belong to a tribe that is acknowledged by the federal government as a sovereign nation within the United States, not subject to state regulations and laws," says Khus-Zarate. "Up through the 1950s, ‘termination’ of Indian land rights was the official federal policy because the goal was to assimilate Indian people. That has since been discredited, but it’s nearly impossible today for terminated or unrecognized tribes without a land base to gain federal recognition."

Without a land base, the ability of tribal people to live together and conduct their business is very limited. The Coastal Band continues to work on gaining federal recognition, but, says Khus-Zarate, "The government chooses not to deal with us. Reparations would be very expensive, and it’s easy for them to say that if you haven’t existed as a tribe all along, we don’t recognize you as a tribe."

To determine how many Indians from which tribes existed in California at the turn of the century, the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs conducted a census. Khus-Zarate believes the Indian population was largely undercounted because of the suspicion native people had of the government.

The BIA also missed counting a few areas entirely, including San Luis Obispo County. Census reports are key to gaining federal recognition.

"Federal recognition and a land base is still denied the nonreservation Chumash, who represent the vast majority of Chumash descendants in contemporary California," according to Anderson. "This situation empowers developmental interests by catering to one very small segment of the Chumash, which encourages factionalism that distracts the people from effectively protecting their heritage sites."

One example of this is the California Commercial Spaceport proposed for development on 100 coastal acres at Vandenberg Air Force Base, which encompasses numerous Chumash religious and village sites. The spaceport would be built on Point Conception, a major sacred area called Humqaq, meaning "the raven comes." Traditional Chumash people still believe it is from this Western Gate that the souls of their dead leave the Earth and begin the long journey to heaven.

In 1979 Pilulaw Khus was one of the leaders of hundreds of Chumash and their supporters in a nearly yearlong occupation of Point Conception to resist construction of a natural gas refinery. The Chumash won that battle, but the pressure to develop is relentless and the field is still nowhere near level.

Khus is nearly 70 now and lives in a rented trailer on a ranch in Morro Bay. Her family had property in Lopez Canyon, but it was condemned when the dam was built and they were forced to move. Her father was Ernest Gallegos, grandson of the famous Chumash/Salinan healer Pacifico, for whom a mountain near the Santa Ynez Reservation is named. She remembers her father telling her when she was young, "This is all our land."

Pilulaw’s son, Michael Khus-Zarate, says, "The American government and people can point to their documents, but justice has never been done."

Why Gambling Matters (and Why It Doesn’t)

Native Americans are the poorest ethnic group in America. According to the Santa Ynez Reservation’s website, unemployment among tribal members was at 80 percent before they opened their gambling hall in 1994–more than twice that of the Depression in the 1930s. Since then the unemployment rate has declined dramatically and welfare payments have been reduced by $50 million.

They also claim to provide 15,000 jobs directly and another 35,000 jobs throughout California, although this could not be confirmed through other sources, and to pay $1.25 billion annually in wages and $120 million in state and local taxes. Additionally, the Santa Ynez Reservation purchases $4 billion in goods and services annually and gives $5 million to charity.

Repeated calls to the business office at Santa Ynez over a period of three weeks to clarify these claims were not returned. This is a common experience, according to several people interviewed for this article.

Mary Trejo, who was delivered by her Chumash grandmother in Lopez Canyon almost 84 years ago, says, "They won’t return calls for anything. They won’t have anything to do with us. I don’t know why, other than we’re not federally recognized and they don’t have to."

Tarren Collins, an attorney with the San Luis Obispo County Chumash Council, says the group has received no acknowledgment of the many inquiries it has made to the Santa Ynez Tribal Council over the past year. "The frustration we feel about their silence and apparent lack of respect and concern has grown," says Collins.

The Santa Ynez website has this to say about the benefits of the gambling operation: "We have improved our reservation with paved roads and brought electricity and sanitary systems to our reservation homes. We provide health care to our tribal members through a medical clinic built on our reservation. Our tribal government hall has been rebuilt. Through established educational and scholarship funds, we provide our tribal members with opportunities to receive vital vocational training and attend colleges and universities.

"The Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians is proud of its new economic stability and its rising stature as a major employer in the Santa Ynez area. The revenues we earn from Indian gaming allow us to plan a future of economic diversification and gain financial independence. We have purchased additional acreage in Santa Ynez with the hopeful intent of developing retail businesses and cultural opportunities. We work to provide for the seventh generation a financially secure future."

Some local environmentalists say that another benefit to tribes is that gambling revenues give them the economic freedom to reject proposals to dump waste or extract oil and mineral resources on reservation land. A number of reservations throughout the United States remain dependent on such industries, which have seriously damaged Indian lands and waters because they are not subject to the regulations that apply on public lands.

Khus-Zarate says the Advisory Council unanimously supports the casinos. "Santa Ynez has an absolute right to do what they want on their land, to practice sovereignty, to be their own independent authority."

But federally recognized tribes with casinos often do not share the wealth. Mark Vigil, chief of the San Luis Obispo Chumash Council, says, "I’m related to some of those people on the reservation. My grandmother had children there. But they won’t open the enrollments. They won’t let you in. I would like to see some of that money go to the elders and to protect our cultural resources, and to help other Indian people get federal recognition. That’s what that money should be used for."

Khus-Zarate says, "It’s true that we get no money from the Chumash Casino, but that goes back to the whole issue of recognized vs. unrecognized status. It sets people up for conflict and poisons the Indian community as a whole.

"We have battled for recognition for many years, long before casinos became so commonplace. We want recognition for other reasons: justice, fairness, our rightful place as nations with the power to uphold and preserve our ways of life." Æ

Freelance writer Terri Dunivant is one-eighth Wyandot, commonly known as Huron.