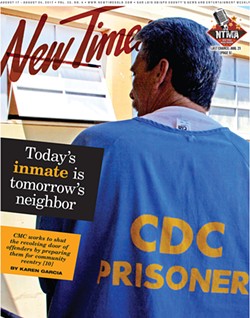

Today's inmate is tomorrow's neighbor

CMC works to shut the revolving door of offenders by preparing them for community reentry

By Karen Garcia[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

Christopher Sheehan walked into a head shop in Huntington Beach with his partner in crime, armed, and ready to rob the joint.

While the two were instructing employees to hand over money, one employee activated a silent alarm. That prompted a nearby police officer patrolling the area to respond to the call.

The officer ordered both men to kneel in front of a wall, but Sheehan argued, distracting the officer. It bought his partner time to shoot at the officer.

Wearing a bulletproof vest at the time, the officer took the shot without injury and fired back, killing Sheehan's partner.

"I grabbed the gun that the officer missed behind my back and fired," Sheehan said.

His bullet missed the officer and Sheehan fled the scene. With a warrant attached to his name, he was eventually arrested in Kern County, Utah, and returned to Orange County.

All of that happened in 1985, when he was only in his early 20s. In July 1986, Sheehan was convicted on felony counts that included attempted murder, robbery, and discharging a firearm. He was also convicted of first-degree murder since his partner died as a result of the crime they were attempting to commit together.

He was sentenced to 37 years to life in prison with the possibility of parole. He's served 31 years at the California Men's Colony (CMC) in San Luis Obispo. With the help of rehabilitation and reentry programs focused on long-term offenders—introduced to CMC in 2014—he walked out of prison a free man on Aug. 11.

He entered a life of barbed wire with the thought that he may not get a chance at parole. At the time, even though he was upset with his situation, Sheehan said he just went with it.

"When I came here in '86, I had no real desire to do anything. I just wanted to have fun, take some classes," he said.

That thought process would change when the prison's approach to its prisoners changed and CMC started focusing on reducing the inmate population and the number of returning offenders. Aside from the academic and vocational programs the prison already offered, in March 2014, CMC began emphasizing structured rehabilitation and community reentry programs.

This move was the eventual result of a 2011 U.S. Supreme Court order for California to drastically shrink the size of its inmate population due to prison over-crowding. With the goal of reducing the number of prisoners in the state's 33 prisons, Gov. Jerry Brown signed Assembly Bill (AB) 109, or public safety realignment. AB 109 allowed non-violent, non-serious, and non-sex offenders to serve their sentence in county jails instead of state prisons.

Kristina Khokhobashvili, public information officer for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, said that once the law was set into place, it allowed for prisons to prepare inmates (with short sentences) for their release.

"Once we didn't have inmates [sleeping] triple-bunked in gyms by the hundreds, we were definitely able to offer more programs, and we were able to fund different types of programs," she said.

At the state level, taking the time to work individually with offenders reduced the return to prison rate to 44.6 percent, Khokhobashvili said. According to a 2015 evaluation report by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, that's a 9.7 percent decrease from the fiscal year 2009-10 return rate of 54.3 percent. CMC has cut its recidivism rate in half.

"The stereotype used to be—and it wasn't altogether untrue—was that we just gave you $200 and said goodbye. But that isn't the case anymore," Khokhobashvili said.

One-way ticket

With a gray head of hair and a silver moustache to match, Sheehan is now 55 years old and has a different outlook than he used to.

In the first half of his time at CMC, Sheehan said he earned his GED, graduated from the machine shop program after 4,119 hours with a B-plus average, and earned certifications within the trade.

But even with those accomplishments, when he went to hearings before the parole board, he was still found to be unfit for parole. He still didn't demonstrate an understanding about the impacts of his crime. Sheehan said he tried to find peace within himself, but there wasn't a group or program in the prison that could aid him in that process.

Things changed in 2014, when CMC brought in the Reentry Hub programs. It focuses on assisting inmates in the lead up to their release. Offenders are required to get their high school diploma or GED, take career and technical programs, cognitive behavioral therapy programs, transitional programs, and are issued a California identification card.

Because Sheehan was serving a life sentence, he didn't believe this new program plan would help him.

"I'm thinking the whole time, 'That's BS.' Another bullet for the Department of Corrections, another bullet for them to have to deny us at the [parole] board," he said.

The Hub program is mandatory for west side inmates, who are serving less than five-year sentences and getting ready to leave CMC, according to Steve Smith, the rehabilitation program manager at CMC. For those on the east side, who are serving life sentences, there is a different plan in place. It's called L-TOP (Long-Term Offender Program), and it's voluntary for east-side inmates.

Similar to the west side curriculum, L-TOP offers substance abuse disorder treatment, criminal thinking, anger management, family relationships, denial management, and victim impact programs.

Sheehan opted in, but was reluctant.

"I had asked the counselors: 'Are you here for the money? Are you here to blow smoke up my ass? What's the deal because I'm done with it,'" he said.

However, it was in the sessions on victim impact and family relationships where Sheehan finally had the chance to dial in on the actual impacts of his crime, the people he's hurt, and find peace for himself.

He said when he realized the counselors were really there to listen to him and to help him, he figured himself out.

"You just have to be willing to be an onion and start peeling back those layers," Sheehan said.

Once the reality of what he had done finally sank in, Sheehan sincerely apologized to the family of his crime partner, who he said has forgiven him. He's also been able to steadily mend his relationship with his parents. Sheehan said the programs helped him realize why he acted the way he did.

"These are things I never thought of. There was no conscience thinking of what I was doing. It was what I wanted to do period," Sheehan said.

Although the L-TOP program does not guarantee that inmates with life sentences will be given a chance at parole, it helped Sheehan realize his faults and figure out where he stood in society. The board found Sheehan suitable for parole earlier this month. He sat down with New Times for an interview on Aug. 10, the day before he was released.

His next steps, he said, are to take it slow and to take others into consideration with his actions.

CMC rehab program manager Smith said that preparing inmates for release and giving them a chance to get back on their feet while having a structure in place has been beneficial to the SLO County-based prison.

"Before, the recidivism rate was 67 percent and two out of every three offenders were coming back. Since then, those numbers have been cut in half," Smith said.

In the last three years, Smith said, Sheehan is the 90th inmate who's been found suitable for parole and has been released.

"We are giving them all the tools because we want our prisons to be calmer, we want our society to be safer, and we want these guys to be successful," he said.

The key

Programs and services that help offenders gain a renewed footing in the community start behind bars and continue after release. For offenders with a diagnosed mental illness, for example, the Department of Rehabilitation is there to guide them through the process of stepping back into society and finding employment.

That aid starts with a letter from the Department of Rehabilitation notifying a prison or jailed offender that they have been identified as a potential client for the department. A return envelope and a business card that sometimes has Linda Benchman's name on it are attached to that letter.

"I've personally counted 166 [clients] and that's just me reaching out with letters. That's not reaching out by telephone and that's not counting the other counselors in this office," she said.

Benchman is a senior rehabilitation counselor with the department who works in SLO County helping offenders with mental illness find employment after being released from jail or prison. All she needs is medical documentation to determine eligibility, so she can work with her client to start writing up a rehabilitation plan and get the offender back to work and into community.

The rest of the groundwork is up to clients.

"My job is basically being a cheerleader. A lot of these people have come in and no one has ever said, 'You can do that,'" Benchman said.

She's a fast talker, putting out as much information as she possibly can about the services that her department can offer with each breath. She said time is of the essence when dealing with her clients; spending too much time on one step of the process means she could lose someone.

"You might find Joe Cocaine, Meth, and Pot. I'm going to lose them, so I try and get their medical record as soon as I can and get them a bus pass right away or clothing right away so they can see that I'm on their side—'Let's help you,'" she said.

When a client begins looking for a job, Benchman can help that person find a business owner or company that is willing to employ the offender and work with the department.

"Our guys can work; they have skills. It's just a process of matching them up to the right job," she said.

Benchman can offer a tax credit to employers, which means an employer can get about $2,400 credit the first year if they hire a client from the department.

Her department also pays for an individual's rap sheet, a record of an individual's criminal history (arrests and prosecutions). And she works with people to figure out how to reduce what's on the sheet or figure out how to own it.

Ownership over those past deeds goes into her client's turn-around speech: the 1-minute ex-convicts have to convince an employer to hire them. Benchman said each client has three 15-second categories to hit within that 60-second speech: Talk about what happened, what your punishment was, and everything positive you've done since then.

"That's your story to tell. You need to be careful with it, and you need to take control of it, end of story. Move on," she said. "I don't think there's one person that doesn't know somebody that's been incarcerated. ... They are going to return to the community and sometimes the community feels weird about it, but they're here."

Using the key

Within a packet of informational pamphlets and documents, Benchman pulled out a list of agencies that the department works with to help its clients. She's just one piece of the pie and can refer clients to agencies that include the Department of Social Services, Community Health Center, America's Job Center, Restorative Justice, Sunny Acres, Gryphon Society, and Jail to Community.

With the help of the whole pie and Benchman's mentorship, Mia Alexander was able to take control of her life after spending most of her young adulthood in and out of the SLO County Jail.

When Alexander was a teenager, she started hanging out with a questionable group of kids.

"I just got in with the wrong crowd of people and started dating someone that I shouldn't have been dating," Alexander said.

It was a mix of bad seeds and drugs that got her into trouble early in her young adult life: "18 years with going in and out of jail and so it progressed to in and out of prison," she said.

But it wasn't until the last time she was put in jail that Alexander got the appropriate help and support system to get her life in order. That was five years ago.

"I just knew that if I continued doing what I was doing, I was just going to go in there and never come out. I have a daughter now, and I was just ready to not repeat history," she said.

Her attorney referred Alexander to the behavioral health court department at the time. She was given a dual diagnosis of being bipolar and a drug addict.

After her diagnosis, Alexander completed an 18-month program through the Gryphon Society. At Gryphon she was referred to Benchman and the services that the Department of Rehabilitation could provide.

With Benchman and the department's help, Alexander graduated from Cuesta College with an associate's degree in Sociology.

"When you sit down with [Benchman], it's your story, it's your goals, and it's what you want to do," Alexander said, "She says 'What do you need to do to get there and how can we help you?'"

When Alexander had trouble getting a computer for school, Benchman was able to supply her with a computer and printer when she graduated from Cuesta. Alexander said it was Benchman cheering her on that helped her make the journey.

"Linda is awesome. She's like a mom that goes above and beyond to help you while standing behind you saying, 'You can do this,'" she said.

Alexander also attributes her success to her probation officer, the directors at Gryphon, and the judge who presided over her case.

"A lot of people saw something in me that I never saw in myself. And my little support system never failed at telling me that," she said.

Alexander is transferring to Cal Poly for the 2017-18 school year to pursue sociology and become a certified drug and alcohol counselor. Her long term goal is to help others who have traveled the path of addiction and want to recover just as she has.

Similar to the recently released Sheehan, Alexander had another chance at becoming a part of the community with the help of services and people working together.

Sheehan gave New Times a call on Aug. 14, just four days after stepping out of CMC.

"When I walk out of here, my support system isn't big but it's 32 years worth of investment in me and me in them," Sheehan said. "I'm free, and it's wonderful to be free, thank you."

Karen Garcia can be reached at [email protected] Δ

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023