[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

“Where exactly am I in this body?”

It’s a question artist Guy Kinnear repeatedly comes back to, both in his work and in our conversation at Steynberg Gallery, where his figure paintings and sketches currently hang.

“Do I inhabit it, or am I it?” he asks.

The search for the elusive, invisible “I” within the fleshy confines of the physical has led Kinnear to produce some striking, beautiful, and disturbing work. Secretly, I hope he never finds it.

For a long time, Kinnear’s paintings began in conversations with his models, unearthing their stories and encrypting them in metaphor and historical imagery. His life drawing subjects don’t pose, they retrace their lives. And the moment they become lost in that action is the moment Kinnear immortalizes them in oil on canvas.

Kinnear is of Neapolitan descent on his mother’s side, a point of pride and an unshakable influence on his work.

“Neapolitans are really earthy people,” he explains. “What is that when you can walk into a church littered with grave sites? There are body parts hanging next to the altar. There’s an interesting kind of disturbingly beautiful, fleshy kind of culture and spirituality there. It’s in my blood, and it doesn’t seem very contradictory.”

Catholicism—whether one chooses to practice or not—is an inseparable part of being Italian, and with it the special Catholic affinity for gory, bleeding, tortured corpses: the suffering of the divine represented as a miserably, grotesquely human event.

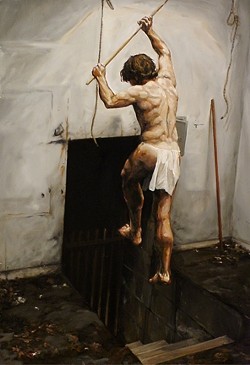

Such imagery is quoted heavily in Kinnear’s earlier body of work “The Gray Rooms,” a collection of paintings depicting a man’s lean, sinewy body—sometimes nude, sometimes cloaked in a loincloth—in a series of extreme poses. Several pieces reference the crucifixion—the man’s arms extended, head hanging in contrition, or death—and yet, tellingly perhaps, we see no cross. The figure seems merely to hang in midair. The causes of his affliction are nowhere to be seen. Several of the paintings in the series depict the figure as an amputee.

In a work titled Limbo, the figure seems to walk on air toward a dark cellar. And yet the placement of his foot aligns curiously with a vertical line created by the layers of stone in the wall beside him, and he seems, quite impossibly, to be tightrope walking.

While no longer a practicing Catholic, Kinnear considers the faith a formative and valuable part of his upbringing and his approach to art.

“I would say it goes back to … that easy comfort with, life is both wonderful and horrific,” he says. “Being oddly comfortable with the idea of a naked tortured man in the center of a church. That’s what it’s like to be a body, to experience the tortures of life, and still say, ‘It’s good.’ That’s the funkiness of Good Friday: to still say, ‘this is good,’ it doesn’t make any sense. It’s preposterous. It’s so ridiculous to say. It sounds like a terrible Friday! And yet we call it good.”

I’m intrigued by a work called Pater Noster: Mater Noster. It’s a painting of a nude couple kneeling near a hive of honeybees. As the man leans into her back, supporting her, the woman ecstatically cups her hands and reaches willingly toward the swarming creatures. It’s a hard one to forget, and I have to ask where such an image came from.

Kinnear and his wife had met the couple in their birthing class, he says, and the pose in which they are depicted is one intended for couples about to give birth.

“We were both marveling that, here’s this process that could take a woman’s life. In third-world countries, it’s the No. 1 cause of death among women. It’s also this incredible, amazing, miraculous activity. And when both the husband and wife are engaged in the process, it can be a miraculous experience. But it’s also a frightening one. It’s a really crazy, life-threatening rite of passage. And so we dialogued about it, you know, what’s this like? And it’s almost like inviting a swarm of bees to build its nest right there in your bedroom.”

The couple is seated indoors, on the carpet beside a window. An inelegant white electrical cord can be seen plugged into a socket, a reminder of the everyday and the mundane in the face of the miraculous, the terrifying, and the sublime.

Kinnear prefers to paint people who have no modeling experience and says his sessions tend to develop extremely organically, working with models to act out a narrative that, though fanciful or absurd, holds a very real, personal story within it.

In a piece called The Sixth Ceiling: Fire! Man!, a bearded, shirtless man rolls off of a mattress, startled, to discover a fire burning in the carpet.

“The piece was with a guy who was a foster father. We were talking about the experience of being a father, and the story that was drawn between it was the story of Joseph, the foster father, and Jesus. What is it like to be told, okay, you’re not only responsible for this kid that’s not yours, but you’re responsible for this kid who’s going to change the world. How do you take responsibility for that? So in our modeling session with him, it was him incarnating his own uncertainty and fear. It was all about that moment of being confronted with something and, that moment of, ‘What am I going to do?’”

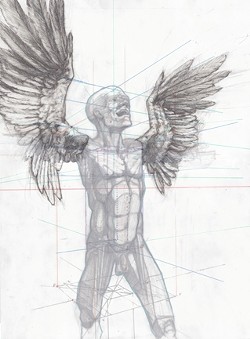

While there is an aura of mystery to these paintings, they appear solid, realistic, complete. Recently, however, as questions like “Am I a body? Am I a spirit?” continue to pervade his thoughts, the artist has begun a series of far simpler graphite sketches, layered on translucent drafting film. They begin with a drawing of a skeleton—Kinnear has one in his studio for reference—and from there he layers on the figure’s muscle, fat, and tissue, often letting the drawing’s strata show through, a glimpse into both human anatomy and his own creative process. There’s a great deal of possibility in these drawings; many conflicting ideas of the eventual solid form allowed to exist softly side by side.

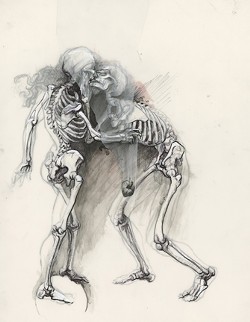

Two skeletons embrace in Just Dropping It, the ethereal suggestion of skin, muscle, and hair barely perceptible. Kinnear riffs off of this image in Who Woulda Thought and That Woulda Been a Different Story, in which he cloaks the lovers in skin, muscle, and clothing, revealing both of them to be men.

One, Two, Cha Cha Cha and Cleave Through and To play similarly with levels of translucency, both depicting a nude couple in one another’s arms, their forms meshing together like ghosts’ forms, so that one’s face might as well belong to the other.

“I’m fascinated by the body. I’m fascinated by the machine of the body. … I think this is just trying to untie that knot and understand it,” Kinnear said of the new work. “There’s a morbid quality to being human. I mean, we produce abjection, we become sick, and skeletons can become symbols of death. … It’s wonderful, it’s beautiful, and it’s horrifying.” He sighs. “I haven’t put my finger on it yet. But probably the second I do, I’ll stop drawing it.”

There are echoes of da Vinci throughout the drawings, an homage to another Italian who explored the disciplines of art and anatomy.

An associate professor of painting and drawing at Azusa Pacific University, Kinnear cites “Sacramental and Incarnational Communication” as a field of expertise. His explanation of what this means is intriguing, if hard to follow.

“I’ll be honest. I have fought with language around it,” he begins. “But ultimately, it’s describing that moment that is being present. A sacrament is a physical sign of an eternal reality. Incarnation is … being in the moment where something really big is caught in a small mundane experience. It’s a moment when you’re absolutely present in your body; you’re absolutely present in the moment, and yet that moment is almost limitless in its experience, experiencing something that all of human history has experienced. Experiencing the divine moment, where the divine flashes through and becomes very mundane. Histories and futures are all tied up in that incredible moment of communication, but maybe what was said, from the outside, it was some ridiculous thing. Minor. It could have been the word ‘okay.’”

Or, perhaps, the words “It is finished.”

Arts Editor Anna Weltner can be reached at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023