One-twentieth of a league under the sea

A multi-agency task force begins assessing Montebello risk

By Matt Fountain[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

When you’re dealing with anything beneath 900 feet of water, nothing is simple. That goes double when that something is a 90-year-old crumbling shipwreck, potentially holding millions of gallons of crude oil next to a marine sanctuary.

When New Times last checked in on the ongoing saga of the S.S. Montebello—the World War II-era oil tanker sunk by a Japanese torpedo some six miles off the Cambria coast—a multi-agency task force had recently formed with the assistance of state Sen. Sam Blakeslee (R-San Luis Obispo), and was gearing up to take the first steps in finding out what, if any, threats the vessel poses to the ecologically fragile central California coastline.

Now, after questions have been accumulating for years, that task force has finally been unleashed upon the doomed ship’s wreckage and it seems there may be answers in sight.

On Oct. 3, the task force—comprised of officers, scientists, and researchers from the U.S. Coast Guard, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, the California Department of Fish and Game’s Office of Spill Prevention and Response (OSPR), Caltrans, the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, and Blakeslee’s office—announced it had awarded a $2.2 million contract to the private Seattle-based firm Global Diving & Salvage to send remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) down to the Montebello to find out how much of her original cargo remains inside—and if she’s likely to release it.

What comes after the current mission depends on the results, of course. But armed with money from a federal trust fund with fees paid by the oil industry—not taxpayers—the momentum is there and officials are eager to finally deal with the Montebello once and for all.

Into the drink

The Montebello was built in 1921 by the Southwestern Shipbuilding Company in San Pedro, Calif., for the Union Oil Company. It spent two decades hobnobbing around the Pacific, delivering petroleum to various ports in the Hawaiian Islands, British Columbia, and even Siberia, before being sent to its watery grave just a few miles off Moonstone Beach.

Only two weeks had passed since the Japanese bombarded Pearl Harbor when the 440-foot vessel loaded up to near capacity with 73,571 barrels of Santa Maria crude at Union Oil’s facility in Port San Luis, bound for a port in Vancouver.

But the crew was aware of rumors of Japanese sub sightings up and down the Pacific Coast; the threat was ominous enough to prompt the Montebello’s captain to resign in protest, leaving the first mate in command.

In the early morning hours of Dec. 23, 1941, the men’s concerns became reality when they received reports of another tanker, the Larry Doheny, taking enemy fire several miles north of their location. Just before sunrise, as the Montebello crept north past the Cambria coastline, two crewmen spotted the Japanese I-21 sub riding along the tanker’s wake. The sub disappeared momentarily, before reappearing on the tanker’s starboard side.

That’s when the Montebello took the fatal hit. The torpedo ruptured the vessel’s starboard bow, narrowly missing its oil tank compartments, which would have surely resulted in a massive fireball and heavy casualties. Instead, all 38 crewmembers aboard were able to escape in four lifeboats, ducking under a rain of machine gun fire from the submarine’s deck guns.

From the water, the crew watched as the tanker, a gaping hole where once there was a bow, dramatically stood upright—as if drawing in one last desperate breath—before vanishing below the surface.

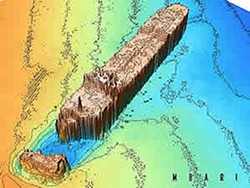

And there the Montebello remained unobserved for almost 60 years, bow completely separated and resting yards away from the body of the vessel.

Though the attack was initially reported in a few newspapers across the nation, the public outside of San Luis Obispo County remained largely unaware of the event. An effort by federal agents to hush up the incident was one part reluctance to acknowledge an enemy presence so close to the coastline—possibly triggering mass hysteria—and another part an effort to save face.

But not everyone forgot about the Montebello. In November 1996, the Central Coast Maritime Museum Association, in collaboration with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA), launched a submarine from the research vessel Cavalier and was the first to capture images of the tanker. Along the way, the sub noted that the hull appeared intact, and tests for a specific strain of bacteria that would have indicated the presence of oil turned up negative.

A subsequent set of dives by researchers from the Monterey Bay Aquarium and archeologists from California State Parks and Caltrans in September 2003 had similar goals in mind—but this time, the results were reason for concern. Though tests for oil leakage were again negative, observers noted visible signs of significant deterioration, including very large rust spots that had formed on the center of each of the Montebello’s tanks.

The dives also revealed a ship that had transformed into an underwater colony for a conservative estimate of 16 species of fish and 29 species of invertebrates, draped in an accumulation of lost fishing nets, in a marine region widely known as a prime fishing location, just outside the southern boundary of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary.

That’s when people outside the scientific community began to take notice. One of the earliest lobbyists for a solution to the potential Montebello problem was retired aircraft radar systems safety engineer and Cambria resident Gary Talley. In 2004, convinced the aging vessel was a ticking time bomb of drastic ecological and economical consequence, Talley wrote then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. He never received a response. Then Talley contacted New Times.

Following an exclusive New Times article profiling the Montebello situation, then-Assemblyman Blakeslee, a former geophysicist, got involved.

“Before the article, I didn’t know much about the Montebello,” Blakeslee said. “But after New Times brought the story forward, it was that last line that really got to me. That ‘nobody’s doing anything about it.’ That made me mad.”

The stakes

Today there are plenty of eyes on the Montebello. No less than four government agencies at the state and federal level, two marine research organizations, one private salvage firm, and one state senator are finally addressing that essential question: What is the risk?

The overall consensus seems to be that the release of three million gallons of crude oil would be devastating to marine life up and down the Central Coast and would decimate the commercial fishing industry, not to mention cause incalculable harm to a local economy driven by tourism dollars.

Any beachcomber in Cambria will say it’s not uncommon to find the occasional tar ball globbed to the sole of your foot after a stroll in the sand, as oil is known to seep naturally from the Earth’s crust into the ocean. But no significant oil presence or sheen was reported in the months or years following the Montebello’s sinking, and though it is possible that a certain amount of oil may have escaped the wreckage steadily throughout the decades, there is no reason to believe there isn’t a large percentage of her cargo still inside her hull.

Perhaps the most relevant case study to the current mission is the S.S. Jacob Luckenbach. Between 1990 and 2003, mystery oil was found fouling the feathers of thousands of birds over a 200-mile stretch of California coastline. An investigation by the OSPR determined that oil samples from the feathers originated from the same source.

Because of the time span involved, officials ruled out a large spill from a single vessel as the cause and instead focused on known sunken vessels in the area. After isolating the source to a 17-mile region southwest of San Francisco, investigators matched the washed-up oil samples with those taken from the Luckenbach, which went down in 1953 after a collision with another vessel, carrying 475,000 gallons of oil on board.

Like the current mission, the Coast Guard and the OSPR formed a unified command to respond to the situation. The spills killed an estimated 50,000 birds, tainted San Francisco beaches, and cost around $20 million to clean up. Hopefully, that won’t be the case here.

Most people with an eye on oil in the water know of the Exxon Valdez, the tanker that soiled roughly 11,000 square miles of open ocean and 1,100 miles of Alaskan coastline after colliding with the Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound in 1989. The Valdez spilled approximately three times the potential capacity of the Montebello, killing some 250,000 seabirds, 2,000 sea otters, 300 harbor seals, and 20 orcas.

The Deepwater Horizon catastrophe in spring 2010—the worst marine oil spill in the history of the industry—oozed some 4.9 million barrels into the Gulf of Mexico over the three months before the successful cap of the wellhead. Cleanup efforts continue in the Gulf more than a year later, and according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the spill’s true ecological effects won’t be known for years to come.

Officials do have some idea of the consequences of a Montebello leak, however. Even with the crude’s thickness, it remains more buoyant than water, and its release and ascent to warmer surface waters could only facilitate its spread.

Melissa Boggs, an OSPR scientist assigned to the taskforce, is here to figure just where that oil would go in a worst-case scenario—what she calls a “chronic release.” Boggs, with the help of $100,000 in OSPR funding and a number of fellow experts—including one Cal Poly professor—has spent months developing models of potential oil dispersal.

Boggs told New Times such models have so far suggested that a leak could potentially show up on beaches near Cambria, just miles from the Montebello site, depending on the conditions. That’s troubling given the wreckage’s proximity to the federally protected sanctuary.

Furthermore, a large enough spill could send oil south to the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant, which relies on saltwater intake to cool its two reactors, and it’s unclear how an intake of crude oil would affect the plant. Jellyfish alone were enough to force a partial shutdown in 2008, and plant operator Pacific Gas & Electric has yet to publicly address the possibility.

Since people are finally on a path to finding answers to these “very scary” scenarios after years of speculation, Blakeslee said he credits the state and federal government agencies’ ability to work together.

“If this weren’t happening, one could really ask if we’ve learned any lessons from cases like the Deepwater Horizon,” Blakeslee told New Times. “Well, this is a counter-lesson.”=

Shipping out to the Montebello

It was unusually warm for an October morning in Morro Bay when the task force began Day 4 of the mission, inviting New Times along for a tour of the mobile command center at the U.S. Coast Guard Station near the Morro Bay Power Plant.

The room bustled with some 15 to 20 scientists, commanders, and officers moving back and forth between stations, coordinating what appeared to be complex logistics and communicating in some form of technical oceanographic jargon. The scientists and consultants held cups of coffee and peered into laptop screens. Fish and Game officers carried guns on their hips.

Only two days before, officials from the Coast Guard, Fish and Game, and employees of Global Diving & Salvage held a press conference to describe the goals of the project and field questions from the media, some from such national outlets as NPR.

The atmosphere two days later was different—busier—and the New Times reporter and photographer inched through the center, attempting to stay out of the way of the task force members who were clearly getting to the thick of their mission.

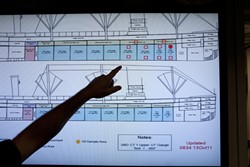

Still, the project’s higher-ups took the time to describe the many charts, grids, and maps collected in the years of research on the Montebello.

Crews have a number of issues to contend with, many unprecedented for this kind of a mission, explained Capt. Roger Laferriere, the federal on-site coordinator for the Coast Guard. Depth, for instance, is a big issue. While the Luckenbach rested in only 180 feet of water, it was also carrying bunker fuel, not heavy crude, the latter of which is much harder to extract.

Lingering at a cool 900 feet, any crude oil aboard is probably the consistency of peanut butter, Laferriere told New Times. How to pump something so thick poses its own dilemma. There are options, he said, including a process known as “hot tapping,” where heated wands are inserted into a drilled hole to warm up the oil globs for pumping, as was successfully employed with the Luckenbach.

But the task force has a few technological tricks up its sleeve, the kind not available to previous dives and missions. Kerry Walsh, project manager for Global Diving & Salvage, explained that the crew would use a neutron-scattering tool to gauge the consistency of whatever lies inside the hull. A special drilling tool would also be used, Walsh said, which would re-seal the holes in the tanks as it pulls out.

Should the crew detect any leakage following the drilling, a heavy-duty magnetic clamp would be fitted over the drill mark to ensure no oil escapes, he added.

New Times’ tour culminated in a three-hour excursion aboard the Fish and Game boat the Bluefin, a law enforcement skiff that patrols the waters between Monterey and the Channel Islands. Aboard, a crew of six under the direct command of Lt. Mark Crossland escorted New Times roughly 20 miles through wind speeds of up to 10 knots and bounded over incoming 9-foot swells.

“Certainly workable,” Crossland chuckled to the reporter, who struggled to maintain his balance.

The destination: Global Diving & Salvage’s massive vessel, the Nanuq, which sat 900 feet directly above the Montebello. Crossing a traveling group of around a hundred or so curious dolphins, the Bluefin came to rest some 70 yards from the Nanuq, whose crew appeared on the deck to wave, Moonstone Beach clear as day in the distance.

Many specific features of the Nanuq are held close by Global Diving & Salvage for competitive reasons.

Crossland pivoted the Bluefin around the vessel to offer a view of the towering cranes, which would lower and retrieve the ROVs from the Montebello site, and which looked similar in mass to those used to demolish small buildings.

But Coast Guard Capt. Laferriere pointed out the importance of handling the Montebello gently. It’s a 90-year-old rusty wreck, after all, and more stress put on its components could cause the very leak everyone’s looking to prevent, as well as damage to a historic artifact.

“The Montebello, she’s our ally in this,” Laferriere said. “We don’t want to make Swiss cheese out of her.”

When will we know?

By the time these words are printed, the risk assessment task force will have a better idea of what they’re dealing with. As of press time, crews had completed their video surveys of the wreckage site and taken some core samples, according to Fish and Game Public Information Officer Andrew Hughan. Drilling was set to begin in just a few hours.

Once samples are obtained, they’ll be taken to an OSPR facility in Rancho Cordova for testing and comparison with samples of oil found along the coast throughout the years and stored in the facility’s database, OSPR’s Boggs said.

The question of what comes next—what to do with the data they get, how to extract any oil and best preserve the vessel, and what can be done with the theoretical oil if it’s extracted—are all lingering questions that remain unanswered.

But first things first.

Staff Writer Matt Fountain lost his sea legs and Staff Photographer Steve E. Miller overdosed on Dramamine. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023