One story at a time

New Times launches The Homeless Project: A common-sense approach to helping more than 3,000 locals who need it.

By New Times Staff Project[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

Occam’s Razor is the principle that, all things being equal, the simpler explanation is generally better than the more complex one.

Our idea is simple, and that’s why we think it’s going to work. It didn’t start as an idea so much as a hope that maybe we could give something back, even just a little bit. Every week we sit in virtual isolation from the real world, looking through our lens, and trying to transmit something in print that might elicit a response or have an impact.

But it’s all so passive.

As writers and photographers and artists, there’s only so much we can do. Most of us couldn’t build a house. We’re not psychiatrists. We’re not drug counselors.

What we do have, though, is a voice and a profound privilege to call for change.

The idea was simple: What can we offer?

It began with a few e-mail exchanges that led to phone calls that led to meetings. We sat and talked and scratched pens on paper.

At first, it felt almost crass, but it seemed so obvious we couldn’t express it any other way:

In almost any newspaper you open, there’s a “pet of the week” section, or something like it. The basic concept is that the paper is the intermediary, connecting a person to a cute homeless animal.

Why not people?

According to the latest local count, there are 3,774 people in San Luis Obispo County who don’t have “permanent housing.” We can’t solve homelessness. It’s too big a monster, and it’s got a centuries-long head start on us. But we can help one person. We can connect one human being with a job or home. And maybe more will follow. And that’s enough.

Because that’s one person whose world could change. An entire lifetime of days that could be made better.

So beginning today, right now, as you read this, New Times is launching “The Homeless Project.” Each week we’ll run a profile of someone in this county who needs help. Maybe they’re looking for a place to crash for a while so they can put an address on a job application that doesn’t lead to a homeless shelter. They might just need a hideout from the temptation of drugs and alcohol on the street. Or perhaps they need a second chance.

Some of the people we’ve met are willing to help around the house. There are ranch hands and handymen. People who’ve said their best quality is simple companionship.

In addition to the weekly features in print, we have established an ever-evolving online database that will include a profile of each person we’ve met. We’ll maintain a list of everyone’s contact information.

Then it’s your turn.

If you think you can help—you have a piece of land where someone can park a trailer, or a spare room, or maybe a job that needs to be done—contact us and we’ll make the connection. We can’t guarantee that everything will work out (we’re not a temp agency, after all, nor a nonprofit) but we know that trying is better than doing nothing.

You can call the New Times office, 546-8208, and ask to speak to someone about “The Homeless Project.” Or e-mail us at [email protected].

At least, that’s the idea. It may fail. But it may also succeed. There are almost 4,000 people who need help, and while helping just one person can seem like a ripple in a pond, remember: That’s a human being with a past, a present, and, maybe with some help, a better future.

Their stories

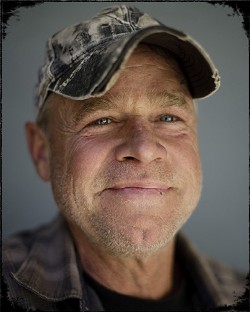

Mike Masters moved from Indiana to California with “visions of palm trees and girls in bikinis.”

He left his hometown and headed west because he was getting in too much trouble back there, he said. Once on the West Coast, Masters started working as a truck driver.

He began work in Los Angeles, then moved to Bakersfield before landing on the Central Coast about two years ago. For a while, things were good. He was working. He has two kids still out in Bakersfield. He’s even a grandfather now.

But a fix-it ticket for his truck was all it took.

He couldn’t pay the ticket, which eventually resulted in an arrest warrant.

“I made the money to pay ’em,” he said. “But I spent it on my kids during Thanksgiving.”

Eventually, he lost his commercial truck license and his job. He began working in a warehouse for a while and at oil fields in Bakersfield—nothing permanent, but something to pay the bills while he tried to get back on the road.

He lost his job and was “pretty much on the curb after that.”

He moved to San Luis Obispo for a change of scenery, spending a bit of time at Sunny Acres. At the moment, he has a friend who’s letting him camp on a piece of SLO property. But Masters is looking to get back to work.

He’s a self-described handyman, who’s worked on friends’ ranches—landscaping, handling cattle, painting. Masters is looking for something more permanent, maybe a place he can stay for a while and work in exchange. In the long run, Masters wants permanent work, enough to help him get a place of his own, “a little place where the kids can come over,” he said.

“Maybe a second chance. How’s that?”

Masters is just one of about a half-dozen people we’ve met, to date.

We first began talking about the project with Becky Jorgeson, a local advocate for the homeless who worked at a clean and sober living facility for three years. Jorgeson said people would approach her constantly, asking how they could help make a difference. For a while, Jorgeson said, she didn’t have an answer for them.

So we started working. After a few meetings, we had solidified a plan: an online database, weekly features, and eventually audio podcasts to coincide with the written profiles.

The logistics, it turned out, were quite simple. We had to set some ground rules—anyone wanting to be featured needed to provide a name, tell his or her story, and sign a short waiver—essentially as a sign of trust.

We want to help people who want to be helped.

“We’re putting names and faces and stories instead of just numbers,” Jorgeson said.

We met people like Brian Lee.

“It all fell apart for different reasons,” he said.

Lee, now 45, grew up in Los Osos. For 17 years, he ran a nursery, growing plants and handling sales. He was a husband and a father.

But Lee admits that he’s long battled alcoholism and is no longer with his wife. And in recent years, he said, he’s had at least two strokes and two seizures.

“I should be 70-something by now, with all I’ve lived through,” he said.

After his first stroke, Lee said, he fell and hit his head. He explained that he spent four days in his car, essentially dead, and then 17 days in a hospital—though his memory of the experience is fuzzy to nonexistent.

His hands now shake. He can’t read well or fill out stacks of papers. He has trouble remembering things short term, long term.

“It’s terrible,” he said. “I can’t remember most of my plants. I used to know every plant in the world.

“I’ve had so much sobriety, it’s brain problems,” he explained. “I know the difference.”

Still, he marvels that he went from near death to walking and talking. He wants to get back to life, though he said he realizes that he’s not getting any better.

He’s been homeless for almost a year at this point. He’s sleeping in his van, though he’s found a bed at a shelter in the past. And he’s trying to get on disability, which, he said, is a fight.

His other long-term goals include earning a stable income, finding a place for himself in Los Osos, and eliminating whatever burden he represents to those who’ve been close to him.

In the short term, he simply wants to move on, move forward. His current condition and situation are hard for him to accept, but he wants to do what he can, and is even considering volunteer work. His hope, however, is tempered by his daily challenges.

“Part of my brain still says I can do everything I’ve ever done,” he said, “which is not the reality.”

It won’t take 10 years

Our approach is different—naive, some might say—because it has to be.

On a recent warm afternoon, county officials, various city councilmembers, and a wide array of homeless advocates gathered for the monthly meeting of the San Luis Obispo County Homeless Services Oversight Council, or HSOC, usually pronounced “H-sock.”

The HSOC is the implementation arm of the county’s “10-Year Plan to End Homelessness.” The plan itself is little more than 86 pages of strategy to coordinate homeless services in the county, and, perhaps most importantly, it’s a sticking point to receive pools of federal funding through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

At the council’s July 20 meeting, they shared stories of helping some of the county’s most severely underserved. They talked money; they talked strategy. But even the HSOC members seemed confused about what they were doing and how to implement the plan set before them.

“The one thing we don’t want HSOC to do is just look like we’re meeting every month and not accomplishing anything,” one member said.

For much of the meeting, the members discussed how and when they were going to sit down and create a plan for how they would implement the 10-year plan, what one person called a “refocusing strategic direction discussion.”

Crafting the plan cost tens of thousands of dollars. The county later shuffled grant funds to HSOC and hired an executive director for $118,720 to begin implementing the 10-year plan.

HSOC Executive Director Patricia Gomez told New Times that the council is trucking along in the implementation phase. The group has hit some milestones since she came on board in mid 2010. So far, Gomez said, they’ve hired two new people in the Department of Social Services as dedicated “benefit advocates” for the homeless. They’ve started a plan to get people on Social Security and Social Security Income more efficiently. And the county has plans to build a “co-located” center for services in San Luis Obispo.

Of course, the plan will never end homelessness—and certainly not in 10 years. It’s not supposed to. HSOC members do speak of success stories, like taking people who are chronically disabled and mentally ill out of hovels they’ve dug under bridges and in the creeks, and getting them into an apartment with specialty care.

But that effort costs thousands of dollars, countless hours of work, and is directed at people who are deemed the most technically homeless by agencies that control funding.

What they do is great. But that’s not what we’re doing.

We’re not bound by funding limitations or red tape. Our plan won’t take 10 years to complete. It won’t require an executive director or a committee to implement. We don’t need thousands of dollars or meetings dedicated to planning the next meeting.

We’re relying on common sense and the blissfully naive assumption that people will help people. And when your goal is to help anyone you can, you can’t fail.

Send offers of assistance to [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023