[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

Sometimes stories I’ve written have haunted me. In 2010, I got a call from Greg Lampert who was the subject of an article I wrote about surfing localism and the violence it can spawn. Mr. Lampert called to tell me I ruined his life.

In the story, I explained how Lampert had been arrested for assault after he got into a fight with Paul Winje, who had cut off Lampert in the waters of Shell Beach. During interviews with Lampert, he revealed a difficult childhood and admitted to a history of violence. Lampert’s story appeared on the cover of New Times on March 23, 2000. His call came more than 10 years after the story was published. He wanted me to print a retraction … 10 years later.

I found the story, “The violent world of Central Coast surfing,” in our archives, re-read it, and felt my reporting was fair and accurate, but Lampert’s call was a reminder that what journalists do can have a real effect on people. It’s never my intent to hurt people or to make their lives more difficult. When people agree to talk to journalists, they’re trusting us to get it right. I take that trust seriously.

More recently, when I wrote about local prostitution in “The oldest profession unmasked” (July 14, 2016), my principal subject, the pseudonym-named DJ Dalton, got cold feet and wanted me to pull the story after I sent her a document with her quotes to confirm accuracy. She felt I made her “sound dumb” even though I recorded the interview and the quotes were verbatim. Luckily, when the final version of the story was published, she approved.

After my cover story “May I have some more, sir” (Aug. 21, 2008) about the California Men’s Colony’s vocational work program was published, I got an email from the sister of a victim killed by one of the men I interviewed. She felt I painted the convicted murderer too sympathetically. Maybe I did. Maybe I should have thought more about the prisoner’s victim and the victim’s family. I still struggle with the pain I caused this woman when she read a story about how well her brother’s killer was doing in his prison work program.

New Times founder Steve Moss always reminded me that a sacred trust exists between newspapers and the public. It’s our job as journalists to get it right. We’re writing about people’s lives, after all, and the stories we tell can have profound effects on individuals long after last week’s issue has been replaced by next week’s. It’s something I try to remember whenever I turn on my computer and place my fingers on the keyboard. I have a photograph of Steve and me on my desk to remind me about that sacred trust and the argumentative, brash, and sometimes abrasive man who taught me how to be a writer.

Senior Staff Writer Glen Starkey has worked at New Times since 1991. Contact him at [email protected].

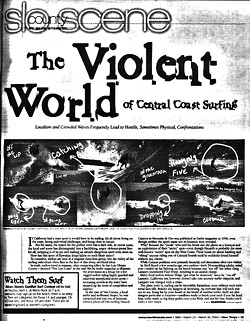

This story was published in full on March 23, 2000.

The violent world of Central Coast surfing

BY GLEN STARKEY

If California had a state sport it would have to be surfing. It’s all about living on the coast, facing individual challenges, and being close to nature.

But for many, the search for the perfect wave has a dark side. In recent years, the local surf scene has disintegrated into a backbiting, angry, violence-prone free-for-all, stripping it of its joy and making an already dangerous sport even more so. …

… In the case of Van Curaza, a local surfer and surfboard shaper, he was ostracized and run out of business when a photo of him surfing Hazard Canyon in Montaña de Oro was published in Surfer magazine in 1996, even though neither the spot’s name nor its location were revealed.

Why? Because the “locals” who surf the break saw the photo as a betrayal and an exploitation of their “secret” spot—even though Hazard’s is probably the most well-known “secret” spot on the West Coast. These locals set about hassling and “vibing” anyone riding one of Curaza’s boards until he suddenly found himself without any clients.

While Curaza’s problems were primarily financial, surf altercations often turn violent.

In Shell Beach a few months ago, two surfers—both 30-something adults, mind you—ended up fist fighting on the beach because one “cut off” the other. Greg Lampert pummeled Paul Winje, resulting in an assault charge.

Many local surfers believe Winje “got what he deserved,” since he “cut off” Lampert. California law, however, doesn’t take into account surfer etiquette, and Lampert was charged with a crime. …

… After the fight, as Lampert was gathering his things and leaving the beach, Winje walked beside him and said, “You’re going to jail.” Winje went up the cliffs and called Pismo Beach police, who pulled Lampert over a few blocks from the beach.

“I feel like I was defending myself, because he started the fight in the water when he endangered me by running his board into me,” said Lampert.

Most surfers agree Winje was in the wrong, but most also agree that Lampert went beyond mere “self-defense,” administering a punishment more severe than the crime warranted.

“If he would have hit me once or twice, I wouldn’t have said anything,” said Winje. “But he kept pounding me. I had to have two of my friends pull him off, and he still wouldn’t let go of my hair!”

Lampert doesn’t understand how he became the bad guy in the eyes of the authorities

“This guy cut me off and ran into me with his board,” said Lampert. “He voluntarily comes to the beach and voluntarily fights me. Well, guess what? He lost, and now he’s hiding behind the police. He could have injured me. These are things people aren’t going to understand and I’m probably going to lose in court, and on top of that he can probably sue me. But it’s not OK to enforce localism.

“I’m not trying to romanticize myself. I don’t hate this dude. I just don’t like that he pulled this localism stuff and then called the police. I hope this story will put pressure on the DA to open his eyes.” …

This story was published in full on Aug. 21, 2008.

May I have some more, sir?

BY GLEN STARKEY

In his own words, Mark Delaplane “killed a guy,” and for the last 32 years, he’s been paying for the crime. He’s gone through all the programs and certifications; he has seemingly been a model prisoner. He exudes an obvious intelligence and reads management books on corporate quality control theories for fun.

Yet when he talks about what he misses most about life outside of prison, this is what he says:

He’d like to walk into a store, buy a fresh peach, and eat it.

“We don’t get fresh fruit in here, just a few mealy apple slices.”

The reason? “They’re afraid we’ll make alcohol with it.”

California’s prisons are overcrowded with inmates with the sort of resourcefulness it takes to turn apples into applejack wine, but, for the most part, their industriousness rarely transcends the prison walls.

This is a story about an exception to that rule.

About three years ago, when Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger issued an edict that state prisons must be reformed, it appeared that a seismic shift had occurred within our state prison system. Schwarzenegger changed the name of the California Department of Corrections to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). Instead of focusing on punishment, California’s prisons would focus on rehabilitating prisoners.

For 700 or so California Men’s Colony (CMC) inmates currently involved in the Prison Industry Authority (PIA) programs, the state’s much ballyhooed promise of rehabilitation feels within reach.

These are the select few men in one of the CMC’s three PIA-managed business enterprises—a shoe factory, a knitting factory, and a printing shop—who are working at coveted jobs, which pay from 30 to 95 cents an hour. These lucky 700 are allowed to work and take classes after work hours to complete their GEDs—the equivalent of a high-school diploma. Other CMC inmates must choose between work and earning a GED. And these 700 men can also participate in certificate programs that train them vocationally, such as forklift operator or hazardous waste disposal certifications that can lead to well-paying jobs on the outside.

Without question, the PIA offers the most successful rehabilitation program in the state prison system. The recidivism rate for inmates who have gone through PIA training is vastly lower than general population inmates—about 25 percent compared to 70 percent. Yet in a state system that currently houses 170,000 prisoners, only 6,900 are employed within PIA programs; for 163,100 prisoners—5,900 of them at CMC—the promise of rehabilitation is, so far, largely unfulfilled.

Adding “Rehabilitation” to the name of the state prison system doesn’t necessarily make it so. …

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023