Dystopia 2.0

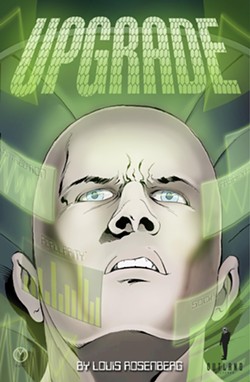

Upgrade, Louis Rosenberg's graphic novel, is science fiction at its most frighteningly familiar

By Anna Weltner[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

Like all great works of science fiction centering on unlikely heroes navigating through dystopian futures, Upgrade succeeds because it’s so chillingly and comically akin to the present.

Louis Rosenberg, a local screenwriter and former Cal Poly professor of mechanical engineering and education technology, has come out with a deliciously satirical graphic novel based on his screenplay of the same name—Part 1 of which was released on Amazon last June.

The year is 2058, and life is lived entirely online, where everything is glowing, bright, and convenient. (The real world, by contrast, is fleetingly depicted as drab, ruined, and shitty.) Online “Members” simply wake up; pull suits that look like adult onesies onto their scrawny, atrophied bodies; hop into their “access modules;” and log in to the System. There, they—meaning their more attractive, better-dressed avatars—navigate their happy, efficient universe. Better still, the Members have regular system upgrades to look forward to—though some find it unsettling to have the features of their lives irreversibly rearranged. (It’s called “upgrade anxiety,” and it’s a bona fide medical condition. You know the feeling you got when you switched to Facebook Timeline and realized you could never go back? It’s like that.)

Enter Avery J. Mankin, algorithms analyst, narrator, and savior of the species.

“Don’t let my pale skin and frail body fool you,” our hero entreats us at the opening of Chapter One. “This is the story of how I save the human race.”

But the tale begins ordinarily enough for Avery J. Mankin, in whose very name the “everyman” is cleverly encoded (echoing, I shall dare to suggest, the noble genericness of Orwellian protagonist Winston Smith). Mankin wakes, enters the System, and installs a sharp-looking suit and a tan, shuffling through these fashion choices like albums on an iPod. He cruises into the mailroom, where a message from his girlfriend is intercepted by an ad for a cream to diffuse a problem called “facial glare.” Then it’s off to work, to the whisper of numbers, patterns, and statistics.

Mankin’s approval index and personal profile are stellar, he tells us. Actually, “exemplary” is the word that keeps getting used. But even this outstanding Member, we learn, has a lifetime of potentially incriminating evidence stored up by a system that sees and hears all. In the background, the System is silently churning, noting word choice and entertainment preferences; scanning for potential underminers of system infrastructure with no sense of irony, humor, or context. When an abnormally large rat breaks into Member Mankin’s residence, smashing his system clock, this evidence finally reaches a tipping point.

Found guilty of such charges as “destruction of system property” and “compromising system integrity,” Mankin is sentenced to a year of exile from the System. Part 1 of Upgrade ends with the pathetic image of Mankin—the thin, onesie-wearing, real Mankin—in his empty, sad, real room, huddled into a miserable ball beside his now-impenetrable access module.

This is just the beginning of the series, the second and third installments of which are due to be released in fall and winter, respectively. The human race has yet to be saved, but already I’m hooked. Rosenberg’s timely yet futuristic story (adapted as a graphic novel by Steven Stern) paired with the clean, glossy artwork of Stan Timmons—is a delight to the senses.

Normally, my personal preferences tend toward more organic-looking illustration than the style Timmons employs in Upgrade. However, given the work’s largely virtual setting, his impossibly straight, flatly colored, computery backgrounds feel appropriate. Timmons expertly contrasts this bright, clean world with the messy, grey one outside—a place where the streets are abandoned save for robots and rats.

I also must admit to a certain bias against lower-case comic sans, which is employed when the narrator is speaking. Too many passive-aggressive notices posted in office break rooms have simply poisoned this font for me. When I read anything in comic sans, I hear an annoying, nasally voice in my head. Fortunately, though, the story’s dialogues are in upper case, which mostly neutralizes the font’s leering offensiveness.

But this is a trifling matter compared to the awesomeness of Rosenberg’s story, a cynical yet funny critique of our internet-addicted culture, and the absurd things it has made acceptable: Our willingness to create an up-to-the-minute profile of ourselves through the use of social media; creating a log of our locations, ages, friends, religious and political affiliations, favorite books, and product preferences—happily becoming part of some giant database in the hands of powerful strangers. Or the way Google follows you around with ads it thinks you will be interested in based on out-of-context words you used in an e-mail, describing this development with words like “intuitive,” where “creepy” might also have applied.

Upgrade’s eerie, secret-free world makes me think, too, of how much easier it is to obtain and share information than it was a mere 20 years ago. I distinctly remember the first time I became aware of some lurking, unseen presence “out there,” collecting and storing information.

My sister and I were kids, and my mom entered our information in a promotional drawing at Baskin Robbins. As a joke, my mom wrote in my sister’s nickname—Hebbler Pebbler, which had evolved from my early, garbled attempts to pronounce “Heather.” Here’s where it gets weird. For the next 20 years, our family received a steady stream of junk mail addressed to “Pebble” Weltner. We changed addresses several times. Pebble Weltner’s mail followed us everywhere. Catalogs, coupons, credit card offers. Telemarketers called, asking for Pebble Weltner. My mom had accidentally brought a decoy into being, and the System seemed to know everything about her—except that she didn’t exist. Before discovering the Internet, before reading 1984, I began to slowly take notice of the world’s creepy, cataloguing underbelly.

In Upgrade, of course, the System is far more powerful and sophisticated, able to file one’s every utterance into a behavior log to be used against them.

“Does this look exemplary to you?” a prosecutor asks at Mankin’s trial, pulling up a video clip of the accused and his girlfriend spooning in bed, our hero whispering, “Don’t you ever wish we could … you know—do that for real?”

“Deviant!” roars the crowd, with all the self-righteous ferocity of a hundred online trolls.

For now, that’s where Rosenberg’s story ends, our hero a frail, whimpering shell of a man with no Internet access. One would think things couldn’t get worse, yet a preview of Part 2 promises scenes of torture and condemnation to come. I can hardly wait!

Arts Editor Anna Weltner doesn’t like anything that’s double-plus ungood. Contact her at [email protected].