'Ancestors of our enemies'

At SLOMA, photographer Donald J. Rommes pays homage to an ancient civilization

By Anna Weltner[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

It’s a strange sight, a home built into a cliff. When, on a hike in southern Utah, this sight first greeted Dr. Donald J. Rommes—neonatologist by profession and photographer in his spare time—the doctor was initially wary of sharing photos of what he’d seen.

The cliff dwellings he’d encountered were just some of many such structures left behind by the Ancestral Puebloans, the indigenous peoples formerly known as the Anasazi. And while the existence of such sites in the area was no secret, Rommes and other hikers had long held to the philosophy that the best way to protect these ancient structures was to keep quiet about them.

“If you wanted to protect something, you would go and enjoy it, but you wouldn’t publish photographs that would draw people to an area that’s fragile and vulnerable,” said Rommes, who lives and works in Santa Maria but was currently on another photography expedition in San Juan County, Utah. “I had embraced the ethic that you came out here and visited it, but you kept the sites and the locations under your hat, and that was the best way to preserve it.”

Over the next two decades, however, as the Internet became more and more ubiquitous, visitors began flocking to areas once inhabited by Ancestral Pueblo peoples—desecrating burial sites, damaging rock art, and dislodging adobe bricks set in place more than 800 years ago, however inadvertently. Graffiti began appearing on cliff walls.

One of these places was a network of canyons in San Juan County called Cedar Mesa, where Rommes had hiked and photographed extensively. Given the growing need to educate visitors about Cedar Mesa, and make a case for its protection (Cedar Mesa is maintained by the Bureau of Land Management, though the region doesn’t currently have a National Conservation Area designation), Rommes was asked to consider using the photographs for some kind of educational effort.

His answer was the new book Cliff Dwellers of Cedar Mesa, published last June, which features his stunning photography alongside text he co-wrote with archeologist William Lipe. Rommes’ photographs of the Cedar Mesa cliff dwellings will also be exhibited at the San Luis Obispo Museum of Art. (The show opens Friday, Aug. 2, with a talk by Rommes followed by an opening reception in conjunction with Art After Dark.)

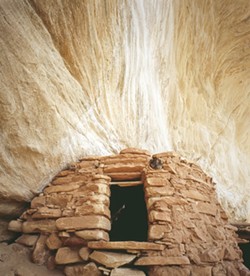

Rommes’ photos are often as compelling artistically as they are important as documents of historical interest. The photographer’s keen eye for texture is clear, as is his exquisite framing and patient way of capturing a sunrise or sunset as its rays play most dramatically across vacant, prehistoric structures. In one image, a small adobe building Rommes identifies as a granary is oriented just so against the white, wispy patterns made by erosion in the rock, echoing the look of smoke, or ghostly white flames.

“There are a lot of natural designs on the canyon walls, and that is probably an area where salt had kind of dripped down with water over the course of time,” Rommes explained of the image. “I saw that as a compositional element, and just kind of moved myself so that the door of the granary would be underneath that flame, which is just basically an artistic device to create a relationship between something on the canyon wall and something of the site.”

Though Rommes takes advantage of such compositional relationships often in the “Cliff Dwellers” series, he also described this particular collection of photos as more representational than much of his other work. Influenced by the landscape photography of Ansel Adams, Rommes had previously been shooting with a large-format camera with black and white film. However, his projects in Utah seemed to demand not only color but also more portable equipment. Though some images in the show harken back to the days of film, many of the more recent photographs were taken with a Rangefinder digital camera.

During his photographic exploration of the sites at Cedar Mesa (“sites” being the word modern-day archeologists prefer to use in place of “ruins,” he explained), Rommes remains confounded and intrigued by the tenacity of prehistoric cliff dwellers to make their homes in such inconvenient, precarious places.

“I think one of the things that is profoundly impressive is that these people went to great pains to build in sites that were very difficult to access,” he said. “They were very defensible, really hard to get to, and the first thing you ask yourself is, why did they do that? … Or, what about the kids, who are running about on these ledges that are 50 or 100 feet above the canyon floor, or more?”

The cliff dwellings could often only be accessed by ladders, which could be pulled up in the case of an enemy attack—which, according to Rommes, was no rare occurrence. (The Ancestral Puebloan people were even named by their enemies, it would seem: the once-common term “Anasazi” is actually a Navajo word roughly translating to “ancient enemy” or “ancestors of our enemies.”)

Around 1250, the cliff dwellers left Cedar Mesa, moving south into Arizona or southeast into New Mexico’s Rio Grande Valley. Archeological evidence suggests that droughts, dwindling natural resources, and frequent raids from nearby clans were all factors in their eventual migration. In addition to their cliff cities and traces of an irrigation system, the Ancestral Puebloans of Cedar Mesa left behind an underground ceremonial structure called the kiva, which is still used by the Hopi and New Mexico Pueblo Indians, their modern-day descendants.

These traces of prehistoric civilization are gradually being eroded, however, by the ravages of our modern one. Over time, sites have been looted of their priceless artifacts; ancient adobe walls have begun to crumble, succumbing to the pressures of frequent visitation.

Ironically, the images Rommes once conscientiously kept to himself are now a major part of Cedar Mesa’s preservation effort. As far as Rommes is aware, Cliff Dwellers is the first book of photographs of the area, with the exception of a few guidebooks.

“The intent and the message of the book really is, you know, look how gorgeous these places are; how interesting,” Rommes said. “Maybe this is an area worthy of protection.”

Arts Editor Anna Weltner takes only photographs, leaves only footprints—if even that. Contact her at [email protected].