[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

When people see his photographs of Chumash rock art, taken at the Los Padres National Forest, Robert Frear wants them to think of the paintings as California’s first and oldest art. The rock drawings date as far back as 1,000 years and end rather abruptly with the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores, a relationship not at all coincidental. Frear documented Chumash rock art sites between 1997 and 2000 in the employ of the Forest Service. His images are part of the SLO Art Center’s show “We Belong to the Earth,” featuring Frear’s photographs, sculpture and installations by Linda Vallejo, and a mural by Sheila Pinkel.

“There is still some power out in these locations, whether it’s strictly an environmental thing or something subconscious within yourself,” said Frear, who visited many sites that the general public does not have access to. “It’s definitely different from anywhere else I’ve been in the Los Padres Forest, hiking or backpacking. The hair on the back of your neck stands up a little bit.”

As a condition of working with the Forest Service, Frear signed a confidentiality agreement stating that he would not show anyone the sites. Many of them were so remote that the average person could not have located them, even with directions from someone who had been there before. A group, including Frear and a Forest Service archaeologist, traveled to a site with a specific purpose in mind; sometimes they wanted to assess the erosion of the paintings, sometimes to correct problems like water damage. According to Frear, they often hiked to a location with 50 to 60 pounds of equipment on their backs; even hauling rocks wasn’t an unusual task during site visits.

The majority of the images were layered onto sandstone, always with organic materials that erode quickly with age. For red, the Chumash used hematite, ochre for yellow, and either charcoal or crumbled basalt for black. Artists then used milkweeds and egg yolks as a binding agent.

Rock art sites were and are considered private, being used in spiritual ceremonies and rituals. Stumbling across someone’s rock art is akin to overhearing a stranger’s prayers, and therefore rude. During his three and a half years with the Forest Service, Frear visited more than 60 sites, each with unique content and purpose. Some are restricted to a single subtle symbol, while others are scattered with more than 80 distinct images. Many locations are inter-generational. Often, a specific site would become associated with a particular need; one might be used to produce rain during a drought. Many of the drawings were produced as part of a vision quest, while the artist was hallucinating under the influence of a traditional Native American plant. Many of the images are accompanied by white dots resembling drug-induced lights.

“We’d get to a site and we’d all have our ideas,” admitted Frear. “It all came down to, we could all be right. We could all be wrong. We have no idea what their context was, what they were feeling, what they were going through. It is so abstract. And it is so other-worldly.”

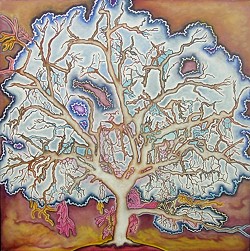

Between 1980 and 1990 Vallejo made more than 100 sculptures, called Tree People, using fragments from trees, procian dyes, and handmade paper.

“I had asked myself, if you could humanize nature what would it look like,” she explained. The answer to her question is faces melded into and emerging from branches. Some faces are subtler than others, the bark split into a moaning “o” of a mouth, a blood-like substance pouring downward, and a bent metal sheet carving into its head. The branches split and arc into arms, or form dual faces, and in Vallejo’s section of the Art Center’s “We Belong to the Earth” exhibit, act as sentinels for her paintings of California landscapes. Her overall purpose is to share nature’s beauty, as well as its vulnerable relationship

to humans.

The Tree People started harmlessly enough. Vallejo has an MFA in printmaking, and found herself pulping leftover paper. Soon, she was bustling around Los Angeles—often in skirts, stockings, and heels—collecting abandoned or felled trees and stuffing them into her van. Her intention was to honor these fallen trees, an effort that started with a lot of waiting for them to dry out. Then she would mix paper into a 10-gallon bucket, along with procian dyes. She strained the muck that resulted from this union, and stuffed it into gaps in her now-dry trees and branches. In its entirety, a single piece took months to complete. But Vallejo could shape a face in a matter of days.

The artist’s contribution to the exhibit is three-part, reflecting her proclivity for many mediums.

At the core of her work, Vallejo installs a mandala with an exterior shell comprised of photographs of pollution and images of indigenous populations praying for the earth. But she also has two portfolios of paintings—Los Cielos and California Horizons—capturing endless and multi-faceted skies, pristine oceans, and mountain ranges that suggest home.

Vallejo’s work is a celebration of California’s beauty and heritage, but also a portent of irreparable consequences, the gut-propelled scream that nature might wish humans to hear. There is, after all, a reason the Art Center elected to say, “we belong to the earth” rather than the more commonly held philosophy that the earth belongs to us.

Arts Editor Ashley Schwellenbach is property of the trees. Send copies of Fern Gully to [email protected].