[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

Editor’s note: In the two months since New Times published an article on the Montebello (“Taking watch on the Montebello,” July 17, 2008), the sunken oil tanker lying a few miles off the Cambria coast, a steady stream of experts, officials, and regular citizens have chimed in with thoughts, offers, and advice on how to prepare in case the oil begins to leak—assuming that it isn’t leaking already. Here’s where things stand.

O

ne thing that’s very clear when it comes to sunken ships is that nothing is entirely clear when it comes to sunken ships. It’s not always obvious who owns them, who’s in charge of them at a given time, who gets the booty if there’s treasure to be had, or who should foot the bill if there’s a mess to be cleaned up.In fact, things get particularly murky in the last scenario.

And murky is an apt metaphor for the Montebello.

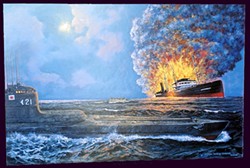

The 440-foot-long Montebello was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, the I-21, two weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor. It was loaded down with more than 75,000 barrels of Santa Maria crude oil—more than 3 million gallons—and had been motoring for just hours after leaving the Union Oil Company’s Avila facility bound for Vancouver before it was hit.

The torpedoes missed the oil compartments, so it didn’t catch fire, but it did sink quickly. All of the crew managed to escape into lifeboats.

And there it sits now, 900 feet down, covered in bioluminescent anemone and draped with fishing nets, about six miles off the coast of Cambria. Two formal expeditions have dived on the ship, the first in 1996 and the most recent in 2003. Divers on the foray five years ago said they found the hull greatly deteriorated since the earlier dive. They didn’t find any evidence that the ship was leaking then.

But what about in the years since?

What if?

Ralph Bishop is a rock hound and an environmental warrior. He’s one of two self-proclaimed “Creek Dogs,” who have been fighting to see Nipomo’s creeks cleaned of pesticides and agricultural debris.

For years he’s made a habit of regularly going to a particular spot on the beach of Cambria—a cove ripe for finding seashells. There, he would fill up a five-gallon bucket with shells and take them to a nursing home, where an elderly lady from his church, no longer able to do her own beachcombing, would spend hours sorting them.

One day a few years ago, as he tells it, she called him up and said: “Ralph, there’s oil on these shells!”

And so Bishop looked more carefully at what he was getting in his buckets, and found she was right.

From then on, he made a point of sorting the shells before giving her the bucket, cleaning out any oil he would find so she wouldn’t get her clothes or hands dirty.

But he always wondered exactly where the oil was coming from, and he had just enough knowledge to be suspicious.

There are natural seeps off the entire Central Coast, and Cambria beachcombers say that for as long as they can recall tar has occasionally washed up on the beach. It’s one of those places where, if you go barefoot in the sand, sometimes you have to wash your feet.

Without question, the oil Bishop and his friend spotted could have come from some of those seeps.

But Ralph Bishop has a unique perspective on oil. As a young man, he said, he worked as a “worm”—not yet a roughneck—in the Santa Maria oil fields. That’s where the oil that went into the hull of the Montebello came from. Bishop strongly suspects that what he found in those buckets of shells was nothing less than the thick crude that he called “elephant snot—straight from hell” when he worked with it as a young man. When he read the New Times account of the ship, he wondered: “Could the Montebello be leaking already?”

Here’s another tantalizing fact: Seabirds are considered the canaries in the coalmine when it comes to nautical spills. Birds such as cormorants that sleep on the water tend to be the first to be oiled when there are spills.

According to the International Bird Rescue Research Center, in March about 200 sick or starving grebes, some oiled, turned up along the stretch of the coast running from Morro Bay south to Santa Barbara. The bulk of the birds came from the Oceano Dunes area. A year earlier, another group of sick grebes turned up. They were collected at Morro Bay’s Pacific Wildlife Care Center. Dani Nicholson, center president, said they found about 18 oiled grebes over the course of a month.

“That’s highly unusual,” she said.

In fact, she said, the center has recently found a number of unexplained oiled birds, but she said regulations require that they all turn up over a short span of time in the same location for a rash of oiled birds to be formally considered a “spill.”

And then there’s this: State oil-spill experts say that in recent winters they’ve seen an increase in the number of “tarballs,” which are exactly what they sound like, that have been reported washing up along Central Coast shores.

Could the Montebello be leaking?

How would they know?

It turns out, mysteries such as this one have been solved before.

Marida Martin is staff chemist for the state-run Petroleum Chemistry Lab in Rancho Cordova. It’s a part of the California Office of Spill Prevention and Response, which was formed in 1991 shortly after the ship American Trader spilled 300,000 gallons of crude oil off Huntington Beach.

When Martin read about the Montebello, she contacted New Times, with a story to tell.

The story goes back to the early 1990s, when each major storm seemed to bring with it reports of tarballs turning up on beaches stretching from Monterey to San Francisco. Was it from natural seeps? Or was it possibly oil extruded from the bilge of passing freighters? Nobody knew.

Eventually things got so bad that in 2002 people began bringing oiled cormorants, murres, and grebes to wildlife facilities for rescue—2,000 in all. The event received an official name: “The San Mateo Mystery Spill.”

The mystery was where the oil was coming from.

Martin explained that her lab can perform a sort of DNA analysis on oil samples and match them, the same way crime scene investigators match fingerprints.

When the oil from the birds was tested, it didn’t match any of the existing samples of sources that the facility had in its databank. It did, however, match three previous spill events that dated as far back as 1992.

The hunt was on. Working from a list of sunken ships that were known to have petroleum on board, Office of Spill Prevention and Response workers narrowed down the list, and then further narrowed it down based on ocean patterns, to a few likely suspects. The Montebello was one early suspect, but was dismissed because of the then-recent dives.

The evidence began to point toward one likely culprit, the S.S. Jacob Luckenbach, which sank in 1953 off San Francisco after colliding with a freighter. It wasn’t until scientists examined high-resolution aerial photographs taken above the site of the wreck, and noticed that the wave action seemed subdued there—an oil sheen would produce just such an effect—that they began to believe they’d found the source.

Martin said a remote-operated vehicle was sent down to explore the wreck but its operators didn’t spot any evidence of leaks until they pulled the vehicle out of the water and noticed a glob of tar on it. Tests later confirmed the obvious: The Luckenbach was the source of the mystery spills.

With its oil the consistency of peanut butter in the cold water, the oil wasn’t spilling out with any regularity. Storms and underwater currents, however, would jostle the boat, causing blobs to rise to the surface and spread as they softened in the warmer water.

What would they do?

In the case of the Luckenbach, the U.S. Coast Guard awarded a $3.5 million contract to Titan Maritime LLC, a Florida-based company with extensive experience in marine salvage, to pump out the oil.

Dick Fairbanks was president of the company when Titan worked on the Luckenbach and he directly managed the operation.

In an interview, he said the oil in the Luckenbach was thick stuff.

“During the Luckenbach job I think we were recording 45-degree water temperature. One of the biggest challenges was getting the oil warm enough in the hull to get it to flow.”

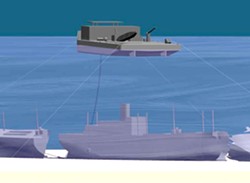

There’s no easy way to pump oil from a broken ship lying hundreds of feet below the ocean’s surface. To solve the problem, Titan created a special heated “wand” that they’d insert into holes drilled into the hold. They’d heat the oil, then divers would vacuum it up to containers on a large barge anchored overhead.

They call the process a “hot tap,” and even at that relatively shallow depth divers would stay for weeks at a time in pressurized living quarters on the barge, to minimize the time and risks associated with decompression.

The Montebello is sitting in much deeper water. Still, Fairbanks said, there’s nothing conceptually preventing Titan from doing the same sort of work on it.

Nothing, that is, except funding and a contract for the work.

“It’s certainly doable if the decision is made to do it,” Fairbanks said. “All the tools we used would probably work in that case.”

He said orders and funding would most likely come from the U.S. Coast Guard, which can access funds from the federal Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund, established by Congress in 1990. Or, the money and direction could come from the state’s own Office of Spill Prevention and Response, which has its own fund.

But realistically, he said, someone would first need to prove that the Montebello is already leaking.

“These things always need a catalyst,” he said.

Calls to the U.S. Coast Guard were not returned.

How could you tell?

Marida Martin, the petroleum chemist, said what she really needs now is a sample of the oil from inside the Montebello.

If she had a sample of the oil, she said, her lab could test it against samples sent to her from oiled birds or washed-ashore tar. Then, even if nothing matches, the lab would be poised to raise the flag the moment a matching sample is found.

“That’s what we really need,” she said, “we need a sample directly from the ship.”

Everyone who has studied the wreck acknowledges that it’s more a question of when, rather than if, the Montebello will leak.

Fairbanks, of Titan Maritime, said the depth of the wreck has likely helped preserve the ship’s hull, but he said it can’t remain intact forever.

Still, getting a sample wouldn’t be easy. It would mean diving the wreck again, likely with a submersible capable of drilling a hole into the hull and taking a sample. And how would you guarantee that the hole itself wouldn’t cause a leak?

Gary Talley is a retired engineer and longtime waterman who has taken an interest in the ship, writing lawmakers and meeting with former military officers.

One idea he’s been proposing is to have a state office pay to fly a small state plane over the wreck site, once every month or two, to search the water for any evidence of spills.

“We should be able to break this thing loose for a couple hundred bucks a shot,” he said, referring to the cost of fuel.

Whatever form it takes, he’s eager to see some sort of monitoring begin.

“We could go for weeks and have oil patches coming up and nobody would ever see it,” he said. “That’s the thing I’m worried about. That’s precisely what happened with the Luckenbach. The oil was coming up for years and nobody was seeing it.”

So far, he hasn’t gotten any direct bites on that idea, but one politician who has taken an interest in the Montebello is State Assemblyman Sam Blakeslee (R-San Luis Obispo).

After talking with Talley, Blakeslee contacted Chevron, the company that bought Unocal, which had evolved from Union Oil Company, to find out more about the wreck.

Blakeslee is scheduled to meet with Chevron officials in the coming weeks, according to an aide.

The facts

The 3 million gallons of crude oil the Montebello contained when it sank is nearly one third the amount spilled by the Exxon Valdez, which contaminated 1,100 miles of coastline in Alaska and 11,000 square miles of ocean, killing between 250,000 and 500,000 birds, at least 1,000 sea otters, 300 harbor seals, and 22 orcas. The fishing industry there was devastated. A study conducted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found that 26,000 gallons of the oil that vessel leaked remained in the soil of the polluted shoreline in 2007, 18 years after the spill, despite extensive cleanup operations.

The Montebello is at the southern edge of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary.

Managing Editor Patrick Howe can be reached at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023