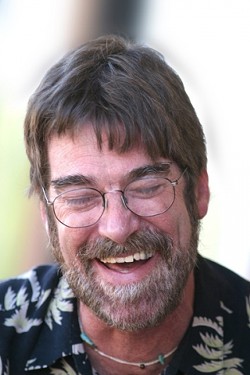

Steve Moss

New times and old times

[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

A brief history of Steve

BY ABRAHAM HYATT

Steve Moss was born Sept. 18, 1948 in Riverside, Calif., the son of Elizabeth and Harry Moss.

He graduated from UC Santa Barbara in 1974 with a degree in fine arts, did some undergraduate work at the now-defunct Brooks Institute of Fine Arts, and some graduate work at Syracuse University in New York. While in Syracuse, he started writing for one of the city's new alt-weeklies. By 1983, he had moved to San Luis Obispo and was working as the editor at what was then called Senior Magazine.

As Steve himself liked to tell the story, when the publisher of that magazine discovered that Steve was thinking about starting his own local paper in 1986, he fired him. Over the next few months, Steve, along with friends Bev Johnson and Alex Zuniga, put together and published the very first issue of New Times.

With his wit, humor, remarkable writing skills, and passion for quality journalism, Steve grew the paper into one of Central California's largest and most-respected weekly papers, one that consistently outshined other local corporate-backed media sources.

"We don't have a hidden agenda at New Times," Steve wrote in 2003. "We don't think we're smarter than our readers. We think the world is complex, not simple; that conflicting issues usually have merit worth pondering on each side, that honorable people can disagree, that Democrats can screw things up as badly as Republicans, and that an environmentalist can become just as much of a nogoodnik as a mall developer.

"We also think life is mostly a fun affair, not an impending disaster - and this sense of fun and playfulness shows in our pages each week, even as we acknowledge that there are indeed ugly things out there in need of a good thrashing."

In 2000, Steve, Bob Rucker, and Zuniga started a successful sister weekly in northern Santa Barbara County, the Santa Maria Sun. The Sun followed a different format than New Times, but Steve's goals were the same. As he liked to say, it was "a town square you can hold in your hands."

Despite a lifelong struggle with clinical depression and epilepsy, Steve was a prolific writer and illustrator, and over the years became internationally known for the contest he started in a 1987 issue of New Times: 55 Fiction. The rules were simple - write a short story in 55 words - and the contest has grown to where it now accepts thousands of entries a year from as far away as Sri Lanka and Pakistan.

His creation spawned countless knockoffs; a play produced in London, England; and even several movie scripts based on the stories. In the 1990s, Steve and Running Press in Philadelphia, Pa. compiled the best of the stories into two books: "The World's Shortest Stories" (1995), and "The World's Shortest Stories of Love and Death" (1998). In 1998, the first title was turned into an audio book; in 2001, the second was translated into Chinese.

The final memory many of us at New Times will have of Steve will be the week before his death as he walked through the office, critiquing story ideas, shaping future issues, laughing at jokes, keeping the paper true to the ideals of journalism he held so high.

He once wrote: "With an alternative paper there's another voice - an alternative voice - for the community to partake of. With the consolidation of mass media today by vast corporate interests, these independent voices are all the more necessary if real knowledge and accurate information is to flourish. Without them, the world would be a poorer place."

Steve was different things to all of us: leader, writer, artist, friend, mentor, inspiration. The world will be a poorer place without him.

He is survived by brothers Harry Jr. of San Francisco, Kioren of Ventura, and Captain Francis Moss and his wife Sharon Jones Moss of Lawton, Okla.; sister Alice Moss of New York City; and by sister Laura Moss and husband Hagan Greer, nephew Alec W. Moss, and niece Georgia Greer, all of Minneapolis, Minn.

Abraham Hyatt is a staff writer at New Times

The best of us

BY GLEN STARKEY

Steve Moss made people nervous.

He was loud, animated; an intellectual razorblade who forced you to engage. In fact he loved to argue, and he didn't care which side he was on as long as someone was on the other. He'd spar back and forth with you for hours only to say after the argument was exhausted and he'd won, "Actually, I agree with you."

He was also the sort of guy who would do anything for a friend. He once lent me $1,000 to buy an old pickup truck, and when I paid him back he marveled - he lent money all the time and no one ever paid him back. He didn't care. He gave because he wanted to and because he could, expecting nothing in return.

Once he returned from an estate sale with a hideous three-foot-long bronze alligator, which with great flourish he presented to me. Then we argued back and forth about whether it was an alligator or a crocodile. We eventually decided it had characteristics of both animals, but out of spite I still call it an alligator. It was fun to abrade Steve because he could take it as well as he could dish it out.

"How's that crocodile I gave you?"

"The alligator is great, thank you very little."

"Its eyes are on the top of its head."

"It has a broad, U-shaped snout."

"So do you."

New Times employees were well acquainted with his generosity: paying for Friday massages, the lunches when we all needed to push to get the paper to the printer, the parties - God there were a lot of them - for Christmas, for summer, for this event or that, someone's new baby, someone's marriage, someone's departure for a new job. Sometimes it seemed like working for Steve was one long-running party.

Sometimes not.

Steve could be extremely pointed, and he was a problem solver. There were days when we seemed to be humming along just fine, and then Steve would burst into the newsroom like a whirlwind, demanding to know what was going on with this or that, disrupting the tranquility of the workplace - a workplace that was never meant to be tranquil.

Steve knew you couldn't slide through the newspaper biz, that you had to run through, arms flailing, shrieking at the top of your lungs. It was an honor and a responsibility to cover the news, and he never let us forget that.

He wasn't a hands-off manager, and sometimes people resented that. But he had an instinct for news, an inquiring mind that couldn't be contained or restrained. And if you were wrong about something, if you made a mistake, he'd let you know. When Steve was in the building, we were all on our toes. He was deeply, profoundly ethical. He made us our best selves.

Those who knew him loved all the various Steves, the intellect and the empathic and the bulldog, but I think my favorite Steve was the cut-up, the card. At one of New Times' Christmas parties a few years back, Steve - as heterosexual as they come - tripped the light fantastic across the dance floor with one of New Times' gay employees. Steve loved people.

Yep, when he smiled his devilish smile, you knew he was up to something naughty, and he frequently was. That was especially evident in his iconoclastic writing, where he'd tilt at whatever sacred institutions were in range. Drinking is bad? Steve wrote a book called "The Power of Positive Drinking." Nothing was sacrosanct, not even himself, and his self-deprecation knew no bounds, evident in his memoir "Seizure Salad," a chronicle of his early years and ongoing battle with epilepsy.

#As robust and towering and vibrant as Steve could be, he had an Achilles' Heel whose root was found in his disease. For the first decade or so that I called him my friend, he had his epilepsy and attendant depression fairly well in check. No, he wasn't always happy, yet his public persona never faltered.

In the last five years or so, however, the medications he took to maintain the chemical imbalance in his otherwise surprisingly agile mind ceased to work. He set off in search of new medications, new doctors, new pathways to return to his former self, but the journey wasn't easy. Most of the new drugs didn't work, or didn't work for long. Often the combinations of treatments left him forgetful and fuzzy, as if under a dark cloud out from which he could come only with great effort. For a man whose whole life and career was tied to his intellect, it was a crushing blow.

His bouts of depression grew longer, his recovery more difficult, his "good times" shorter lived. Yet he never stopped worrying about others, never stopped asking me if everything was okay, if I needed anything. Watching Steve deteriorate and knowing that he was always ready to give help but never ready to receive it was difficult to say the least. His battle was within his own body, and he accepted that it was a battle we would have to wage alone.

In the end, it was the one fight he couldn't win. But I won't remember that Steve. I'll remember the Steve who used to sock me in the arm and ask me how I was doing, the Steve who would show up at my house with a bottle of Scotch and a story, the Steve who would hand me something weird like the sock monkey that sits on my desk and say, "This reminded me of you so I got it for you." Now it reminds me of him.

Steve was a maverick. He was a leader. He was a friend. He was the best of us, and we'll miss him.

Glen Starkey has written for New Times since 1990.

Steve Moss' wild ride

BY CHRISTOPHER GARDNER

Steve Moss was fearless. He could talk to anyone, anywhere, at any time. Whether they were cab drivers, famous writers, aspiring writers, politicians, panhandlers, millionaires, merchants, or simply strangers on the street, Steve could strike up a conversation and learn about the other's universe. His appetite for new people, places, and experiences was insatiable. My favorite memories of Steve are walking around downtown working on the New Times column "Street Talk." He loved going up to strangers and engaging them in dialogue; talking, listening, and eliciting fascinating answers to mundane questions. Steve could never understand writers who didn't love doing this. To him it was a treat, an excuse to pry into the lives of our fellow human beings. He would think nothing of walking into a shop and asking the counter person what was going on - what was important in their world. A mere two-block walk to Sandy's deli would yield five story ideas. Woe to the reporter who did not have three or four stories cooking at any given time. I'll miss Steve; his heart, his imagination, and his fearless quality of embracing the unknown. I know that wherever he is now, Steve is asking question after question.

Christopher Gardner is New Times' photographer .

The dog who could see the rainbow

BY RYAN MILLER

You always trusted me.

That's probably what I'll remember most about you. From when I was an intern to the last time I saw you, Steve, you trusted me. I know because you told me, and I know because other people told me that you told them. I know, too, because you treated me like you trusted me. Your trust was more than just words, but then, even words were more than just words to you. You loved words, and I loved words, and maybe that was enough.

I was just out of college. I had put in six months' worth of a once-a-week internship at the Sun, and suddenly I was arts editor, full-time. I didn't know what I was doing. I didn't have a clue. And then, as these things go, I was managing editor, and then I was editor, and I had even less of a clue what to do. I was a kid, and I was in charge of a newspaper, and I was scared out of my mind. But ultimately I could handle it, because you weren't acting worried, so I didn't worry. Much.

I remember how you would show up in the office after driving down from San Luis Obispo and you would tell me how the Santa Maria Sun should be more than a paper. You would tell all of us. It should be a place, you'd say, a physical place where people could meet and gather and share news and ideas. "A town square you could hold in your hand," you'd call it. Over and over, you'd call it that.

We were sick of that phrase, of that description of our paper, but you were always right, and maybe we were sick of that, too. You had this way of circumventing logic and somehow coming out at the end with something that still made sense, and we had to agree that what you said made sense, even if how you said it didn't, and we weren't really sick of any of it after all.

And then we'd go to lunch, and we'd all talk and laugh, and sometimes you'd laugh so hard you would kick the chair in front of you, or the table leg, and one time, you stabbed me in the arm with a fork. Remember that? I think it was an accident because you were laughing so hard, but when somebody asked why you jabbed me, you said you wanted to see if I'd bleed. We were shocked for a second, and then we laughed again, because it was so funny.

Is that what you're doing now? All the reports say that your death was an accident, was due to "natural causes" while you were out gardening, and I believe it was an accident, but I also can't help but wonder whether you also just wanted to see how we would react.

Well, we're bleeding, Steve. We're all bleeding here without you. This one cut us deep. You still had so much to say, or at least I still had so much I wanted to hear and read and learn from you.

You started two newspapers with your bare hands. You corresponded with Ray Bradbury, my favorite author, and showed me the letters and drawings you exchanged. You even gave me his address, though he's never written me back. You lent me books and borrowed my DVDs and discovered earth-shattering concepts in even the most mundane films, and then you'd tell me everything: paradoxes and revelations and the futility of being the one dog who can see color and trying to explain a rainbow to the other dogs, all stuck in a monochrome world.

When I first started as editor here at the Sun, you told me to ask you if I ever needed any help, and I asked you for help on more than one occasion, and you would tell me exactly what to do, and then later you would tell me what you would do in my place, and then later you would tell me you didn't know what to do, and what did I think I should do?

It felt like you were pulling away, even then, like you were slowly backing off, making sure that I could handle things if and when you weren't around any more. You visited less, and when you did come around, you had that sad sort of smile you wore so often toward the end.

It's easy to say what I'm about to say because I'm looking back, but in my heart I know it's true and not just hindsight. When I last saw you, three or four days before you died, you walked behind me, and you squeezed my shoulder, and you left your hand there for a moment longer on my shoulder, and it felt like a goodbye. The last goodbye.

Well, Steve. You said to ask, no matter what, so I'm asking. I still need your help here at the Sun. We all do.

You're still here, after all, in a way. You loved words, Steve. You loved their beauty and their power and the change they could bring to those who read or heard them. When you died, you left behind a lot of words, Steve, and for us, maybe that will be enough. It'll have to be.

Ryan Miller is the editor of the Santa Maria Sun.

The teacher

BY JOHN PEABODY

Be fair, be accurate, and never arrogant

On my first day at New Times I sat in Steve's office as he explained his expectations of a good paper to me. Steve's words were refreshing and really resonated. Steve told me, with a smile, that one of his goals with New Times was to "never be arrogant."

I'll never forget that.

So many alt-weeklies are arrogant, pretentious, so hip it hurts, and so not really a good alternative to the mainstream press.

Steve knew this. He new that too many alt-weeklies are something like the "papers for the cool kids," and the rest of us aren't hip enough to read them. Steve felt that we should offer a genuine alternative to the daily, one that normal, non-hipster types want to read - that means writing news briefs, covering some business, and never being arrogant.

I quickly discovered that it was this philosophy that had given New Times the credibility that a lot of other alt-weeklies and dailies don't have. At first I might not have liked this, but I've learned it is the most useful tool a reporter can have - trust and credibility.

Steve also always stressed being fair and accurate. If we were doing a story that would potentially have big, negative impacts, it was a must to be fair and accurate. It was okay to take someone to task as long as we followed these rules.

Just last week, with deadline fast approaching, Steve and I sat in his corner office and talked about the war in Iraq. Steve's brother had been recently deployed to Iraq and I told Steve that I was been working on a story about a guardsman who is also going there. Steve and I disagreed about the importance of winning the war in Iraq, but his arguments, somewhat based on a book about tactical warfare operations of Alexander the Great, were intelligent, compassionate, and lucid.

That was a good day in Steve's office and I loved it. I've learned, especially after meeting and hanging out with Steve, that when you get the opportunity to interact and exist with someone like him, you must seize it, even if means you'll be late for deadline. I learned from Steve what I now consider to be pillars of good journalism - be fair, be accurate, and never be arrogant.

John Peabody is a staff writer at New Times.

The community advocate

BY TOM FULKS

Steve Moss used to laugh a lot. He got a kick out of people who appeared to be full of themselves. He'd say the folks who move to San Luis Obispo County and brag to their friends back home about how nice it is here - encouraging even more of them to come - reminded him of "strutting peacocks who preen their feathers all day yet don't think anything of crapping in their own nests." He made me laugh a lot.

Once we were walking down Monterey Street, going out for a movie or a beer, and this woman in a BMW 7 series drove by. She was on her cell phone yammering away, looking in the rearview mirror not at traffic, but working over her mascara, steering with her elbows.

"She thinks she's perfect," Steve mused, "and I bet she's as messed up as me." Then he slugged me on the shoulder so hard it hurt, and he laughed out loud. Sometimes Steve laughed so loud I'd look around self consciously to see if anyone was staring at us.

#Oddly enough, Steve couldn't care less that people stared at him while he laughed, but he cared deeply about what people he knew thought of him and his newspaper. He was hard on himself, too hard most of the time. He didn't laugh enough during the past couple of years. Lately, he'd been judging himself against a standard he could never meet. The good thing about that, ironically, is what it did to New Times. The self-criticism made the newspaper better, I think, and my hope is that it will continue to improve even without Steve.

He had a knack for seeing the truth in things that others, me included, didn't always see until it was pointed out. It was one of those gifts that made Steve a very special person, the kind of guy you'd hate to let down because he'd always know it no matter how hard you might try to hide it. It was a trait that shaped the character of New Times over the years.

Many years ago, when the other media players in the county were beginning to focus a lot of attention on the skyrocketing cost of housing - quoting local real estate types that it was simply a matter of the Central Coast "catching up" with the rest of coastal California's home prices - Steve, if I remember correctly, ordered up a story about local renters and the troubles they were having collecting their deposits back from stingy landlords. He wanted readers to know that not everyone was benefiting from the real estate feeding frenzy and that greed has victims.

Steve didn't hesitate to raise questions very few people were willing to ask, like the time Cal Poly students rioted in 1991, smashing windows and raising hell, all for the righteous cause of "free beer." All the other media stories focused on how rotten the students had behaved, and how they deserved to have their heads bashed in by the cops, and how Cal Poly President Warren Baker was right to cancel Poly Royal forever.

Steve posed some troubling questions publicly, uncomfortably, about whether it might not be a good idea to examine the behavior of the police during the riot. He thought it might be worthwhile to study if some of the officers on the street may have been a little trigger happy, so to speak, and whether or not a possible police overreaction - borne from fear, inexperience, or lack of training - might have played some role in the behavior of the rioting students. In the end, the police behavior was shown to be professional and right, but the questions wouldn't have been answered, the introspection wouldn't have occurred, if Steve hadn't asked. (Tellingly, the same questions were not asked during the latest go-round of riots at Cal Poly during Mardi Gras 2004.)

The fact that Steve Moss had asked the questions at all, in the face of near unanimous public support for the police actions during the 1991 riot, was testament to his belief that the media's role isn't to be a cheerleader for the street-level instruments of government policy, but to be a skeptical observer whose role is to make sure government is held accountable even when "the people" don't want to know. Today, that position can make a publisher very unpopular with his readers and his government, the difference today being the Patriot Act and all the disturbing Big Brotherism that goes with it.

Steve liked taking on people he perceived to be high and mighty. The story that best illustrates his jones for fat cats was that of Carl Hagmaier, a local life insurance broker back in the 1990s who liked to display his wealth with ostentatious shows of extravagance: fancy cars, high-dollar bids for bottles of wine at the snooty KCBX dinner auction, a house on the green at the country club. The problem was, Hagmaier didn't earn his loot - he stole it from the pension funds of local businesses that were his customers. Hagmaier went to prison, and Steve got a kick out of it. He boasted over drinks one evening that one of the genuine joys of owning a newspaper was to be able to help bring down a crooked high roller.

Steve elevated New Times from an arts and entertainment rag to a real newspaper. This stimulated competition for stories and exclusives, and, in my opinion, pushed the Tribune into becoming a better newspaper because of it. We all benefited from Steve's push for more and better news coverage, for ferreting out important stories that other media missed.

While Steve was dogged in his journalistic principles, he was more so when it came to his quest to find an answer to the pernicious and persistent mental illness that hounded him for the last few years of his life. It was this unwillingness to quit the search, I think, that has enhanced my admiration for Steve Moss more than anything else he achieved in his life. Steve waged a lifelong struggle with epilepsy and, in his last years, was at war with the chronic, debilitating depression that accompanied it.

Through it all, he accomplished more - writing and editing books, publishing one newspaper, launching another, building a landmark downtown edifice, keeping up with friends, helping those in need - with more dignity and class than anyone else I know. Many people would have simply given up and let the illness overtake them. Steve waged warfare with it. He never accepted his mental illness as something to be tolerated as an irritating side effect of epilepsy's medication regimen. Most courageously, he never tried to hide it.

Steve wrote a book about his conflict with depression. He'd been shopping it around, looking for a publisher, like the one that published his 55 Fiction books. He asked me to read it, and I'm ashamed to say that I couldn't get through the first couple of chapters because of my own personal demons. It was just too true, too real, for me to handle. And so I quit on him, and he said, "Yeah, okay, you don't have to read it, but I wish you would, but I don't think any less of you, though I'm disappointed you didn't because I wanted to talk with you about it."

Oh, how I wish now that I hadn't let him down.

I'm comforted, though, by the thought that Steve Moss is feeling better now. His battle is won, he can laugh again. Peace is in his grasp.

And for that I say fare thee well, my friend. Fare thee well.

Tom Fulks is a longtime friend of Steve Moss.

Searching for truth

BY RICHARD JACKOWAY

Journalists love to lead off news obituaries with an anecdote, preferably 100 words or less, that sums up the deceased's life, character, and impact on the community.

Despite knowing Steve Moss for 16 years and working with him for seven, I have no such tale to tell. That's for the best. Steve would have detested such artifice. Steve knew, better than most, that people were more complicated than that. Steve was always searching for the truth - in journalism, in other people, and in himself. And like most quests for knowledge, the more he learned the more elusive the answers became.

I worked as Steve's managing editor longer than anyone. It wasn't always easy. That's a truth. But it was often the most fun I've ever had in journalism. That's also true.

I will remember Steve for his vision of journalism without barriers, an all-too rare thing these days. I will remember him as a fierce debater (particularly when he was wrong), a creative soul, an unapologetic deadline-buster, a gifted writer, a sharp wit, a chaotic manager, and a generous friend.

I will remember Steve for all of what he was. He would have expected no less.

Richard Jackoway was New Times' managing

editor from 1993-2000.

Thank you, Steve

BY STACEY ANDERSON

Thank you, Steve, for leading by an example I will always remember.

Thanks for listening patiently to all my insane story ideas, for treating me like a professional, and for laughing when I pretended to steal the solar-system toy in your office.

Thanks for taking a chance on me - first as an intern, later as an editor, and always as an equal contributor to a wonderful staff of friends. Thanks for setting up a publication that demands the whole story and makes us work hard for it. Thanks for giving me career and life advice - often when I least expected it, and usually when I needed it most.

Thank you for everything.

Stacey Anderson is New Times' calendar editor.

A man of extremes

BY MARLA PUGH

When I came to work for Steve Moss, he threatened to fire me my first day. He had hired me to be the founding editor of the Santa Maria Sun, New Times' sister publication, and didn't think I was making as much progress as I should in my first eight hours.

I remember the conversation clearly. We sat in the Sun office until 8 p.m. discussing his concerns. When I tried to defend myself, he got pissed off, telling me I should just listen. Then he got pissed off because he said I wasn't saying enough.

A few weeks later, when the first issue of the Sun came out shining, Steve literally skipped into the newsroom, grabbed me in the biggest bear hug of my life, and kissed me for my efforts. Although I thought he may have cracked some of my ribs, his smile and gratitude made it worthwhile.

That was the Steve Moss I knew. He was a man of extremes. Extreme brilliance, extreme expectations, and extreme kindness.

Steve's creativity and passion were so huge, they enveloped you. From the first day I met Steve, I wanted to hang out with him and learn from him. I admired his ideas about what journalism should be, not to mention his incredible talent for putting words together, whether it was in a story, an ad, or an e-mail.

But most of all, I admired his guts.

In a time when mainstream newspapers were getting more and more afraid to call people on the carpet, Steve still had the balls to shake things up. To hell with the big guy. Standing up for the little guy was important to him - more important than profits and lawsuits. That was what kept so many journalists in his corner. We knew we were fighting the good fight when we were on Steve's team. Wimps need not apply.

#Sometimes it wasn't easy working for a man of such extremes, and such strong ideas. But it was always, always a hell of a ride. He'd push you, prod you, and challenge you. He'd try to piss people off, felt it was his duty even. But he would be devastated to know he really hurt anyone's feelings unnecessarily. And if he thought you were in trouble, he was there. Steve could be as good of a friend as a newspaperman. I was lucky to know him as both.

That's also probably why Steve earned the respect of so many people who worked for him. We were a strange family, bound by Steve playing the role of the eccentric uncle. We were often dysfunctional, sometimes pissed off at each other. But when threatened from the outside, we stood by each other - stood by Steve, with a fierce loyalty people outside the family would be hard pressed to understand.

The essence of New Times was - and I hope always will be - Steve Moss. His extreme personality lives on in the paper he created. My hope is that New Times will continue to push, prod, and piss people off. But in the end, Steve would want it to put people first. That's the legacy he leaves behind.

Goodbye Steve. Thanks for not firing me that first day. If you had, I would have missed out on a great mentor and friend. You made the world a more interesting place to be in, and it won't be the same without you.

Marla J. Pugh was New Times' managing editor from 2000-2002.

Stranger than fiction

BY KING HARRIS

Steve Moss was born without a single loss for word nor idea.

Unleashed in bold type, both would eventually provide passage for anyone searching for fun, foolishness, and the truth.

A weekly walk on the wild side. One step ahead.

It was his life.

It was his gift.

Thanks for giving me New Times, Steve.

King Harris is managing editor of New Times.

‘This is my ship'

BY STACEY WARDE

One day, out of the blue, I received an e-mail from Steve Moss, publisher of New Times: "Don't you love me anymore?"

I'd never held any hard feelings against Steve. I always thought he was a little strange, but I had no bad feelings about him.

Receiving an e-mail like that was a little odd, too. Steve and I had never been palsy walsy. I hardly knew the guy. So, I knew something was up.

I hadn't done much for New Times since writing a cover story on gay marriage in SLO County for the bridal issue.

The story didn't go over too well with advertisers but it's the kind of story Steve approved and liked.

It let readers know about a slice of life you wouldn't get in any other local publication, except New Times.

Steve needed help, badly. And I needed work.

He'd lost a string of managing editors, and things weren't going so well at the paper.

Steve wasn't the easiest person to work for, and he was picky about everything that went into his paper.

He brought me in as a "utility" player. He made it clear that our relationship would be based not on love so much as running a ship.

"This is my ship," he said. "I like smooth sailing." He appointed me associate editor, and later, managing editor.

Two weeks into the job, I called Rick Jackoway, who was then working at the Tribune as city editor and had been managing editor of New Times during its Golden Era.

"Jeez, Rick, how did you do it?"

I had seen a side of Steve that I'd only heard about - the difficult publisher who could make life miserable for everyone.

Often, Rick said, he saw his job as an intervener. "Keep Steve out of people's hair," Rick suggested.

I didn't really know how to do that, but I spent as much time with Steve as I could, hoping that would help.

I learned a lot from him during those many long hours in his office, discussing how to run the paper, but mostly on how to make it interesting and fun.

Steve Moss loved newspapering, and he was an editorial wunderkind. He attacked hard stories with glee, and he loved to tell a good story, and to tell it well.

I also learned that life wasn't always easy for Steve. When he read the first chapter of his book on epilepsy, I thought he was beautifully describing an acid trip, not his first painful experience with a seizure.

Periodically, I'd pass by his office during the crunch of our weekly Wednesday deadline, and he'd be zoning out in front of his computer. Two hours later I'd pass by again, and he'd still be there, staring blankly at the wall or sleeping.

We kidded around the editorial office about it, left Steve alone and gave him his space. Sooner or later, we knew, he'd snap out of it.

I realize now, two days after his death from a seizure and collapse, that he was probably experiencing a micro-seizure, or facing something like a monster from a bad acid trip during those off days.

I only hope that his last moments weren't as scary or as confusing as his very first moments from a seizure. There always seemed to be light at the end of the tunnel for Steve, even in his darkest moments.

I'll miss Steve Moss, and his meticulous and cantankerous care for the ship he loved. I hope his sailing is smoother than ever now.

And, yes Steve, I still love you.

Stacey Warde was managing editor of New Times from 2003-2004.

A man ahead of his time

BY TODD KLEFFMAN

Having come to New Times with a strictly button-down, mainstream background in journalism, it was a wonder for me to work under Steve in the kind of freewheeling, creative environment he fostered at the paper. I know that I stretched my boundaries at New Times, both personally and professionally, and enjoyed my time there as well as any over my career, which is now pushing 20 years. It's interesting, looking back now that I've returned to the mainstream media again, how many papers today are struggling to retain readers by emulating the kind of fun, dynamic, and relevant product Steve was putting out 10 years ago. He'll really be missed, but he leaves behind a great legacy.

Todd Kleffman was associate editor of New Times

from 1991-1993.

One of the few

BY KENNETH NEILL

Steve Moss was a man of ideas.

Now that's an understatement.

Indeed, given his long struggle with epilepsy, he always struck me as someone who just wished his body would get out of the way, and let him get on with the business of his always-visceral quest for truth and knowledge.

I remember a time some 15 years ago, when I was visiting Steve and Bev Johnson at their home high on a hill outside San Luis Obispo. It was a beautiful Sunday evening, and my then-teenage daughter Molly was with me. All of us were helping to prepare a farewell dinner, upon which we could feast before driving to L.A. to catch the red-eye back to Memphis.

We were younger then, Steve and I, and full of enough piss and vinegar to curdle a tanker-truck full of milk. Evidently the impact was not so severe upon the wine we were drinking, so the evening was lovely and lively, to say the least.

We were all together, in the open kitchen, engaged in some heavy-duty, planet-transforming dialogue, when Steve's hand slipped over the steaks he was trimming, carving a significant gash in his own hand.

It looked pretty ugly, I remember. But Steve simply grabbed a towel, and kept right on talking, determined not to let a little thing like blood dripping all over the counter get in the way of our vibrant conversation. Dinner was wonderful, of course, although the household's supply of towels was pretty much exhausted, by the time we drove off to L.A. Only after we got home to Memphis and called back to California did we learn that Bev had dragged Steve off to the emergency room the minute after we left, where the staff scolded him severely for his stupidity and used something like 30 stitches to close his wound.

That was Steve. Mind over matter, always, even when neither wanted to cooperate.

Our friend was a brilliant, gifted writer, of course, but nothing he wrote ever gave him more pleasure than the introduction he wrote for a little book he self-published in 1997, an essay titled "The Book of the Few." The essay itself was actually written by his father, Harry Walter Moss Sr., a lawyer in Riverside who left the essay in manuscript form in his personal papers, where Steve discovered it when his father died in 1989.

"The Book of the Few" is a remarkable essay on the subject of the Book of Genesis, in which Mr. Moss Sr. offers the thesis that the first book of the Bible was actually a parable about the Tree of Knowledge, and that Genesis only became a "religious" document when modified by later transcribers intent on turning it into a morality tale. His argument struck me as brilliant when Steve first showed the manuscript to me, now as I reread it, the essay seems especially relevant in the midst of our nation's current church-state travails.

When I heard about Steve's passing, I immediately pulled out my copy of "The Book of the Few," dimly recalling that the final few paragraphs of his father's essay contained just the sentiments that Steve would want to have recalled at this difficult time for all those who loved him. See if you agree:

"I assure you that valuing knowledge and forever seeking it will always bring rewards. But it will also bring much loneliness. This is another truth that the story in Genesis is attempting to convey.

"Because if you decide to seek knowledge, you will become one of the few. Like Adam and Eve, you will become an outcast; you will have left the garden, venturing into the unknown.

"And as one of the few, you won't be liked very much by those who place little trust in that strange god of yours who is always changing and reinventing Himself as new facts are added.

"So be courageous in your search. Take pride in those who hate or envy you. And get used to it.

"One more thing: Always remember the prayer to the god of Knowledge. It is simple to utter and it goes like this: ‘I don't know.'

"It's easy to say, so say it often and you will learn forever. Never forget that being able to say it is the beginning of all knowledge."

Steve Moss never forgot, never for a moment. We will miss him dearly

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023