Imminent development?

Residents air their concerns as plans for the massive Spanish Springs project inch toward reality

By Nick Powell[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

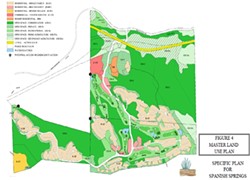

The city of Pismo Beach has had its municipal eye on the rolling green hills between Price Canyon and Oak Park Road for 20 years now, and on Feb. 5, the City Council is expected to make a decision that could literally pave the way for construction on the large swath of undeveloped land currently under the jurisdiction of San Luis Obispo County.

Should they accept the Spanish Springs Specific Plan, a final environmental impact report, revisions to the city’s general plan, an agreement with the developer, and a fiscal analysis that shows Pismo pocketing roughly $650,000 per year in additional revenue at build out, the city would be free to take the next and most important step before construction commences: applying to the Land Agency Formation Commission (LAFCO)—a seven-member board tasked with managing the growth of cities throughout the county—for permission to annex three large parcels covering 961 acres.

The city’s last request to LAFCO (annexation of the 154-acre Los Robles del Mar area) was denied for lack of water in early 2012, resulting in an ongoing battle over legal fees.

Without annexation, the land near Price Canyon is relatively worthless, capable of supporting just a few houses using well water and county services. But once developers have access to city resources, they plan to build 370 single-family homes, 103 condo or apartment units, a 320-bed retirement center for seniors, a 150-room hotel, a nine-hole golf course, and several parks.

Despite the years of effort that went into drafting and revising those plans, many residents view them as seriously flawed and doubt whether some key components will ever fall into place.

“If LAFCO approves the development, there’s no more control,” Sheila Blake said. “[The developers] will be able to do whatever the hell they want, and that’s what’s so scary.”

Blake ran for a seat on the city council during the last election cycle, and although she lost, she remains politically active, especially in the fight against Spanish Springs. She and a handful of collaborators spearhead a group called “Save Price Canyon,” which runs a website of the same name, combs through planning documents for flaws, and distributes fliers calling for citizen participation during public hearings.

According to Blake, the group has an active membership of about 10 people and an e-mail list with the names of more than 200 supporters from all walks of life.

“It’s reasonable opposition,” Blake said. “We’re not people with pitchforks.”

Recently, Blake and Susan Testa, who opposes Spanish Springs even though her house-painting husband could potentially score dozens of contracts from the development, took New Times on a little field trip around the perimeter of the project to highlight their trepidations.

While Blake’s concerns were mostly environmental, Testa focused on the looming influx of motorists. According to the plans, one sleepy suburban street, Highland Drive, will bear the brunt of the project’s traffic impacts, at least during the first phases of construction. Commercial trucks and emergency vehicles (remember that retirement center?) will have no other access to the site until an inland arterial road is built.

Such a road is drawn into the eastern section of plans and scheduled for the second phase of construction, but it will have to cross Pismo Creek to connect to Price Canyon Road, a major feat that’s barely touched upon in the final environmental impact report. The document says only that a flood plain study must be done prior to submittal of the tentative tract map that includes the bridge. Testa doubts it will ever be built at the proposed location, but she noticed that the city has been trying for years to secure federal funding for the replacement of a rusting, iron bridge across the creek at Bello Street, right behind the city’s wastewater treatment plant.

The bridge has been closed for 30 years, and the dirt roads leading to it don’t really go anywhere, yet.

“It doesn’t connect anything except the development,” Testa said. “They’ve been so sly about this.”

There’s no mention of the Bello Street Bridge in any Spanish Springs documents, but it does lead to Frady Lane, which is listed as a potential emergency access point at the western end of the development. The road is currently just a paved walking path near the oddball development jeeringly known as “Driveways Del Mar,” which sits just inside the city line and will eventually feed into Spanish Springs—if it’s approved. The area features two parallel roads, connected like a ladder by four small crossways. There’s room enough for dozens of houses, but only four lots have been developed since the area was graded and paved in 2009. For Testa, the area sends a clear message that there’s no demand for development in Price Canyon.

Community Development Director Jon Biggs attributes the lack of activity to the recession, which he believes has passed. He said the city took advantage of the lull in construction to go beyond the typical call of duty in its efforts to draft plans that would best suit the city and satisfy developers with as few impacts as possible. A constraints study was prepared in 2009, identifying potential problems that could arise during construction, including the development’s impact on traffic, which Biggs claimed would be minimal.

“Everyone at the city staff level, and the developer, understands the importance of getting that [arterial] built,” Biggs said. “The people living there, yes, they will realize more cars on the street, but they won’t be waiting in traffic for minutes.”

Biggs identified several areas where the developer made concessions to satisfy concerned citizens. For example, an entire parcel was removed from the plans; 72 percent of the area will be open space or parks open to the public; 22 acres originally slated for development won’t be disturbed; and the developer will pay $3.5 million to upgrade the water treatment facility so that it can produce recycled water suitable for irrigation.

Blake and Testa weren’t impressed with the concessions, noting that the city plans to charge builders reduced water connection fees for savings that will equal the cost of plant upgrades.

“It’s the same old plan,” Testa said. “It’s not new. They’ve just dressed it up a bit.”

Biggs said that the water connection fees were fairly reduced, considering that the project will be using less potable water than originally estimated.

The first round of plans brought forward in 2010 featured input from three separate property owners, but all three parcels have since been acquired by BHT II Pismo, LLC, a subsidiary of a Southern California development company. The purchase price on two of the parcels was not available to the public, but the smallest parcel, the 182-acre Loughead Ranch, was purchased for $389,000 in 2010 according to county documents. Stephen Hester, a partner in the firm, refused to disclose the company’s expected profits from the project and expressed frustration with the public outcry.

“The opposition isn’t really justified,” Hester said. “There’s a lot of misinformation floating around.”

A two-part public hearing on the project will wrap up Feb. 5. The City Council already heard a staff report and (mostly oppositional) public comment on Jan. 15, but the applicant, Steve Hester of BHT II Pismo, LLC, will have a chance to speak at the coming meeting. The public will again be given the opportunity to comment, and City Council members will be able to ask questions and discuss the issue before voting.

Four of the five council members have previously deliberated on Spanish Springs and shown support for the overall goals of the project, but newcomer Eric Howell expressed concerns during his campaign.

During the last meeting’s public comment session, many citizens called for a city-wide vote on the project. Should the council vote to accept the planning documents, opponents would have 30 days after their final adoption to circulate a petition and collect signatures from 10 percent of the city’s 5,577 registered voters in order to override the council’s decision with a referendum. Fifteen percent of voters would need to sign in order to call for a special election on an initiative to quash the project.

Staff Writer Nick Powell can be reached at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023