[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

Many people might be surprised to learn that, when it comes to weather, the term El Niño actually refers to a seasonal condition, not a huge storm.

“People do the same thing with monsoons; it’s a season, not a storm,” KSBY Meteorologist Dave Hovde told New Times in a recent interview. “It’s a condition, it’s like fall.”

And just like fall has certain expected weather patterns, so does El Niño—namely, rain.

A consortium of big-name weather groups, including the National Weather Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, currently predicts there’s a 70 percent chance of El Niño arriving this summer and an 80 percent chance of it coming during the fall or early winter.

But don’t break out the sand bags and heavy-duty rain gear just yet: Experts are also predicting that the season will peak at weak to moderate strength.

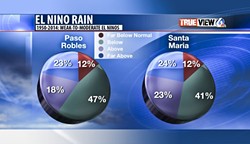

“While an El Niño is likely, the strength of it is not certain, and … that is critical,” Hovde explained. “A strong El Niño has a strong correlation to heavier than average rainfall locally, but the weaker flavors of El Niño are 50-50, if not leaning to even a slight chance of drier than average rainfall.

“In strong El Niño conditions,” he continued, “the jet stream pattern comes to California from the southwest and picks up a lot of strength and develops low pressure, which directly intersects [the state] on a fairly regular basis and can produce the badly needed rain.”

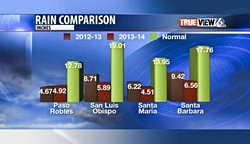

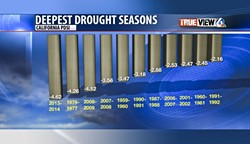

And that moisture is desperately needed: This year was the driest year on record for California, according to the Palmer Drought Severity Index. Experts have called the 2013-2014 drought a 500-year event, meaning a scarcity of this severity only happens once every five centuries.

Additionally, a study funded by the California Department of Food and Agriculture and UC Davis finds that the net water shortage caused by the 2014 drought will result in $810 million in crop revenue losses and $203 million losses for dairy and other livestock, plus an additional $454 million in groundwater pumping expenses. The total statewide economic cost of this year’s drought is estimated at $2.2 billion, with a loss of more than 17,000 seasonal and part-time jobs.

With the nation’s fruit basket hurting so badly, a wet year is critical. Unfortunately, the meteorological jury is still out on whether the skies will deliver.

“Ocean water temps show warming, but atmospheric changes are yet to develop,” Hovde explained. “Warmer than average ocean water temps redirect the jet stream, and then the jet stream dips into the lower latitudes and picks up moisture and comes to the Central Coast.”

The stronger the contrast in temperatures between latitudes, he said, the stronger the jet stream.

“A stronger jet stream creates low pressure, or what we call storms here in California,” he said. “But we need to be mindful that a weak to moderate El Niño will create another [year of] lower than average rainfall.”

What we need, Hovde said, is for conditions to strengthen.

“I’d say there’s still reason to be optimistic,” he said. “[El Niño] is like a kid growing up; not all kids grow at the same rate.”

While we’re behind 1997 in terms of atmospheric conditions, there’s still time for things to start changing. But the extreme weather patterns experienced in the last decade do raise questions about climate change and its impact on arid states like California.

“[Climate change] is happening: Scientific groups almost universally align in their belief in the evidence,” Hovde said.

Such groups as the World Meteorological Organization, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the American Meteorological Society, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science have all issued statements in recent years concluding human activities are modifying Earth’s climate.

“The preponderance of data in regard to climate change is hard to deny,” Hovde said. “[Climate] doesn’t impact seasonal or daily forecasts, but we have seen record temperatures and drought.”

He explained that climate “is an after-the-fact assessment” of data, so “we do need some distance from events.”

“It’s become a political football right now, but it’s happening,” he said. “Asking how many people should live in an arid state like California— that’s a legitimate question—or how much water should be used on agriculture versus development. These are issues we’re dealing with right now.”

Amy Asman is managing editor of the Sun, New Times’ sister paper to the south. Contact her at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023