A return to the Montebello

Prompted by a New Times series, task-force members plan a new reconnaissance mission

By Patrick Howe[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

One by one they grinned, backslapped, and handshook their way past each other into the small conference room. Here—attended by his earnest aides—was Assemblyman Sam Blakeslee, the lawmaker who had gathered the group together.

Already at the table, fiddling with the projector, was the oil-spill expert with the sardonic sense of humor (his screen-saver image was an explosively burning oil platform). Beside him was the methodical environmental scientist, and in the back was the Coast Guard Captain, standing straight as a spar. There was also the silver-haired don’t-call-him-a-lawyer lawyer and, finally, the enthusiastic sunken-ship expert and historian keen for a return trip in a yellow submarine.

You could see anticipation in their eyes and feel it in their energy, like young boys eyeing a remote-controlled toy monster truck under the Christmas tree. Their topic for the day was something to be excited about, a possible way to use their expertise, the tools and toys of their trade, and a bit of the government’s money, to accomplish something important.

Brought together in a roundabout way by New Times’ own reporting, the group that was gathered in the newspaper’s conference room represented most of the key players in a task force that, among other things, plans to return to the Montebello, a 90-year-old sunken oil tanker thought to be holding some 3 million gallons of oil in its rusting hull, to assess just how likely it is to rupture and release its cargo. A report due this summer will discuss whether there’s oil on board, and what might happen if it leaks.

After that work is done, all they’ll have to do is figure out a way to do something about it.

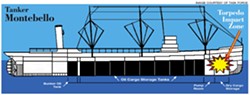

Her story

America woke to news of war when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. People on the Central Coast learned just how brazen the Japanese had become two weeks after the assault, with the sinking of the Montebello. The 440-foot-long tanker was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, the I-21, while motoring out of port from the now-defunct Union Oil Co. facility in Avila. It was on its way to Vancouver, having embarked despite losing one captain who refused to board amid reports that Japanese submarines were stalking tankers. Somehow, the torpedo missed the oil-filled holds and instead hit the pump room and dry storage area, taking out the upper wheelhouse in the process. Thankfully for the crew, the boat sank fairly slowly, giving enough time for all of them to escape into lifeboats, even though the Japanese submarine’s deck guns were shooting rounds just over their heads.

And it sits there still, in 900 feet of cold ocean, six miles off of Moonstone Beach with a broken bow but otherwise sitting eerily upright as if she were still motoring in 1941.

And so comes the worry. Assuming the oil is still there, and assuming the ship won’t hold its cargo forever, what should be done?

If the experience of other sunken tankers serves as a guide, the Montebello isn’t likely to give up the 3 million gallons thought to be in her tanks all at once. Barring a failure of her rivets, it isn’t likely that a massive hole will suddenly appear in the large hull walls that were, after all, designed to keep oil inside them.

Where might those viscous globs and tarballs head?

That’s Melissa Bogg’s job to figure out. Boggs is an environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Game’s Office of Spill Prevention and Response.

Armed with $100,000 from California’s Office of Oil Spill Prevention and Response that the task force has at its disposal, she’s already working with a Cal Poly scientist to come up with models of where the oil might head when and if it emerges. One of the models she’s working on is designed to assess where the globs might head in just such a “chronic” release. Using ocean currents and existing models for her work, she’s already come up with a preliminary model.

But that all assumes the ship isn’t leaking already, and Boggs isn’t one to make assumptions.

To that end, she has collected tar samples off the beaches of Cambria and a laboratory is analyzing them. Even with results, they won’t be able to say for certain that the oil in the samples came from the Montebello, but they should be able to say, for example, if they came from the Santa Maria oil fields, the source of the ship’s oil. It would be circumstantial evidence at best, but it could help with efforts to tap state and federal spill-cleanup funds.

Another of the key questions is what would happen in a “catastrophic” release, in which large portions of the oil come out at once after, say, an earthquake. Such a scenario, in the crisp word choices of Coast Guard Captain John Caplis, another task force leader is: “Low probability, high consequence.”

Boggs is modeling that possibility as well.

Among the reasons Blakeslee said he put the task force together:

-The wreck sits just south of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, a federally protected marine area that stretches from Marin to Cambria. Officials worry a spill could impact habitat, wildlife, and archeological sites.

-The Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant is well within the coastline that could be impacted from a spill. A Cambria man, Gary Talley, a retired engineer who has taken an interest in the Montebello, petitioned the Diablo Canyon Independent Safety Committee in 2008 to set up monitoring systems to detect oil heading toward the plant’s intake valves. Jellyfish alone managed to force a partial shutdown in 2008 after they covered intake racks.

-Complicating things further, the ship is itself not only an ecological threat but also both a historic artifact and a maritime oasis for sea life; she’s draped in torn nets because it’s long been considered a prime fishing habitat. If endangered species are determined to be affected by any work on the ship, it could make the whole matter far more complicated.

How does a state leaking profound amounts of money justify spending anything, let alone the potential millions of dollars, on a ship that as far as anyone knows isn’t yet leaking oil?

It won’t be an easy bill to fill. Caplis, of the Coast Guard, who was involved with the efforts to drain the Luckenbach, noted that tab was paid with funds from the Federal Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund, created after the Exxon Valdez went aground. Paid for with fees from the oil industry, the fund defrays cleanup operations when there’s no “responsible party,” but also when an incident is deemed caused by an “Act of God” or, interestingly with regard to the Montebello, an “Act of War.” The Luckenbach was costly but the Montebello is in far deeper water with potentially far more oil.

That’s not the only potential funding source. The money for the task force came from an “Imminent Threat Fund” and another state Fish and Game fund has money siphoned from a 5-cents-per-barrel assessment on crude oil transfers that move through state waters. Yet Blakeslee noted it might be difficult to attract any of those funds until the Montebello actually starts to leak.

In the case of the Lukenbach, mystery spills soiled beaches for years before the problem was tracked to its source and cleanup began. “We had thousands of sea birds washing up,” Caplis said. “Hopefully that’s not how we’re going to find out about the Montebello.”

Hopefully.

For all his apparent ambitions and bedrock conservatism, the former Assembly Minority Leader has another side, one more reflective of the geophysicist he once was. Blakeslee said he likes “big system problems,” complex situations that don’t fit neatly into a box or any one bureaucratic flowchart. Sunken oil tankers are just such a problem.

Plus, he reads New Times. Blakeslee said he knew nothing of the Montebello’s threats until New Times published articles on the ship in 2008. “I was totally intrigued … here’s this giant potential problem and no one wants to own it.”

With a mess of bureaucracies involved and no one really in charge, he noted that sunken ships are an easy problem to ignore. “But when you think about the implications of not getting it right, you think ‘Someone’s got to own this,’” the assemblyman said.

And so Blakeslee began working to own it, contacting the descendent of the company that once owned it and coordinating experts from six state and federal agencies in an effort to at least assess the threat the ship poses and, hopefully, put in place a monitoring system or even a plan to drain the ship of her cargo. The task force has been together for a year.

Next, he said, he plans to put together a bill that will act as a vessel should urgent action—and money—be called for.

It wasn’t as though, before this task force was assembled, the Montebello was unknown. It’s sinking was reported in the Telegram Tribune when it happened and articles about it had been written periodically over the years. Robert Schwemmer, of the federal National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, has been following the ship’s history for years and even boarded a yellow submarine, the Delta, to dive it. It’s been surveyed twice—once in 1996 and once in 2003. No telltale signs of oil leaks were discovered, but divers said it appeared to have deteriorated by the second dive.

If anyone can be said to have continued to ring the bell of concern about the Montebello, it is Schwemmer. His title is a mouthful but Schwemmer’s role with NOAA has him coordinating investigations and research into the five marine sanctuaries along the West Coast.

While the task force anticipates another dive on the wreck in coming months, it’s unclear what form that will take: It may be explored via an unmanned sub.

One of the primary questions the task force has ahead of them is finding out whether there’s still oil on board. It’s conceivable she lost some, all, or most of her cargo when she sank, although Schwemmer said survivors do not recall seeing a telltale slick. So now the team plans to dive the wreck, to precisely map its position and videotape the ship.

Then comes one of the many tricky parts of the operation: Finding out if there’s oil on board. Of course, they could simply drill into the tanks, but task-force members note this idea has risks. For one thing, it could cause just the sort of slow spill they’re concerned about. It sounds simple but, as Judd Muskat, staff environmental scientist for OSRA noted: “We’re 900 feet down. It’s costly and dangerous.”

Other goals of the task force are to study the stability of the ocean floor in the area—possibly toward the construction of an undersea platform from which to launch an operation.

At the very least, the task-force members plan to launch some means of monitoring the wreck site for leaks. That could be satellite-based, microwave pulse radar used to look for patterns of unusually still water—the sort of stillness caused by oil slicks. It could mean a buoy-based monitoring system fixed above the wreck. Or, it could mean flying over the wreck periodically in a Fish and Game aircraft outfitted with special sensor equipment.

“It’s important to let the public know that we do have agencies now that are looking at the Montebello,” said Steve Sawyer, the attorney with the Office of Spill Prevention and Response.

The dive is planned to occur in the next couple of months, said Muskat. There are plenty of obstacles to be worked out, but money for the dive isn’t one of them.

There’s so much they don’t know, but the prospect of funding in a time of scarcity has made them popular men.

Sawyer told a story about attending a “Wrecks of the World” conference on the East Coast, where most sunken ships and the bulk of the salvage industry are located. They ignored the California boy right up to the point where he mentioned how far along the task force was in assessing the Montebello.

“Then I became the most popular guy in the room.”

Talley, a former quality-control and safety engineer with Hughes Aircraft, isn’t satisfied with what he’s heard so far from the task force. To make his point, Talley reached into comedy history to invoke Bill Cosby’s tale of the Chicken Heart That Ate New York.

Just like the chicken heart, Talley says, at some point “That oil’s going to be coming out.” And, just like the chicken heart, “It’s going to be coming at us.”

Talley’s own analysis puts the odds of material fatigue that would lead to a spill—likely due to corrosion that breaks through the rivets holding the cargo walls together—at about 25 percent each year.

He wants two things: He wants regular flights to begin immediately that would survey the wreck area for spills, and he wants the Coast Guard to immediately begin conducting training exercises in the region in preparation for a potential spill. While Muskat says flights are already planned, the Coast Guard couldn’t immediately respond to the latter request.

“It can travel five miles really fast,” Talley warned, “So they’d better darn well be ready.”

Patrick Howe is the former managing editor of New Times. Contact him at [email protected]

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023