California's silent oil rush

An unregulated drilling method could tap 15.5 billion barrels of oil

By Robert A. Mcdonald[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

The Central Coast’s hills and plains are known for their beauty, their wildlife, and their isolation. Aside from the resident animals and the occasional vineyard, town, farm, or ranch, much of the land in Monterey, Santa Barbara, and San Luis Obispo counties lacks human presence.

Soon, that may all change.

Underneath much of the area lie millions of cubic miles of shale, a brittle, porous material that wouldn’t draw interest from anyone except perhaps a geologist in search of a master’s thesis.

But that shale is now drawing interest from far more than academics.

Oil executives, investment bankers, and government officials have begun to talk about this shale in the same hushed tones gold miners use when they think they may have found another Sutter’s Mill. What they say is shocking, but if the federal government is to be believed, it’s also quite possibly true.

Monterey shale, the enormous mineral formation that runs through much of coastal and central California, may hold the fate of the economic future of the United States. Among oil speculators, this area is quietly becoming the hottest potential investment in the West.

Generations of locals who’ve walked these hills and valleys never knew they were treading over land that may one day produce billions of barrels of oil. The federal government recently declared that the shale may produce enough oil to surpass Mexico in production.

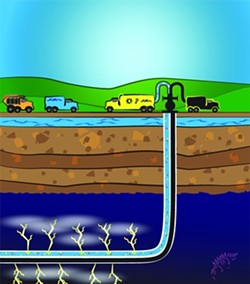

To get at the oil won’t be easy, but new technological breakthroughs developed in the last few years have opened up the door to tap these reserves: Thermal fracking, a process by which water and small amounts of chemicals are injected into the ground at high pressure to free up the oil, is a controversial procedure that’s troubling environmentalists across the country.

Holy Texas tea, Batman, that’s a lot of oil!

In July, the U.S. Energy Information Administration released its estimates of readily recoverable gas and oil within all the shale deposits in the United States. This obscure report didn’t make many waves—except in a small community of geologists and petroleum engineers who noticed the significance of its findings.

Drilling for oil and gas in shale is the newest and hottest trend in the energy industry. Recovering gas from shale has been highly successful in the eastern United States, and petroleum companies have begun to bring oil out of the shale in places like the Bakken fields in North Dakota and Eagle Ford fields in Texas. Oil production in those fields has been so productive, it’s outpaced the industry’s ability to transport it.

The report said the Monterey shale formation contained 15.5 billion barrels of oil, accounting for 64 percent of the total shale oil resources in the United States. By those numbers, the Monterey reserves dwarf those at the Bakken and Eagle Ford fields.

The federal estimates came as a shock to many in the industry. If the numbers in the report are true, new onshore oil fields might easily pump up the nation’s oil output by 25 percent in just a few years.

The report affirmed what many oil speculators had been claiming for years: California might be the center of a new oil boom. If it’s right, California has more recoverable reserves in its shale than big oil-producing countries like Mexico, Brazil, or Angola. If all of California’s oil can be extracted, it could equal Saudi Arabia’s output for more than a decade. It would be more oil than Alaska has produced in the last 25 years.

This potential new petroleum kingdom not only has gas executives drooling, it’s brought together people who disagree on just about everything.

Bringing Republicans and Obama together

In what’s come as a surprise to many, the Obama administration has hopped on board the shale bandwagon and the controversial methods used to get to the oil and gas. Steven Chu, the U.S. secretary of energy, recently appeared before a congressional committee to talk about the nation’s energy outlook.

Members of Congress quizzed Chu about what they perceived as the declining domestic oil output. (Until the advent of fracking techniques on shale, the nation’s output was considered likely to be in decline.)

“If you look at the total oil production of the United States, again, there are some uncertainties, but we’re actually seeing increased oil production in the continental United States,” Chu told the committee. “And we’re actually expecting to see an increase in oil production from the fracking of shale rock. And again, it’s uncertain how much that will grow, but already it’s a couple hundred thousand barrels a day of production. It could increase to over a million barrels a day in the near future.”

New drilling is expected to raise U.S. oil production by at least 20 percent in the next five years—and might reduce oil imports by 50 percent in 10 years. Even if these numbers are optimistic, a shale boom could mean the nation’s dependency on foreign oil can be reduced while preserving environmentally sensitive regions like the Arctic reserve or offshore areas.

Shale drilling for oil and gas also produces something politicians particularly crave: jobs. Some eastern states that have significant shale drilling have been adding hundreds of thousands of jobs to areas that were economically destitute. The great recession seemed to have bypassed North Dakota, and many analysts attribute its 3.8 percent unemployment rate to the shale boom there.

Presumably because of this, the Obama administration has followed the lead of the Bush administration in its fracking policies. The big hitch in this new world of domestic oil production would seem to be hydraulic fracturing (the technical term for fracking). However, the federal government has a unique regulatory attitude toward the practice, specifically that there is no federal regulation for fracking.

Can’t touch this

Fracking received a specific exception from the Clean Water Act in the 2005 Energy Bill. Because of this, oil companies don’t have to reveal what chemicals they use in the fracking mixture. California doesn’t regulate fracking, either, nor does it keep track of the practice in any way.

The lax regulation miffs Steve Craig, a spokesman for Halt Oil Lease Drilling Now (HOLD), a citizens group that would like to stop fracking in California. Craig lives on a ranch in southern Monterey County, and he’s seen firsthand the fracking revolution. A gas company called Venoco Inc. has begun to drill exploratory wells in the area. And Craig wants a moratorium on fracking in California.

Craig and others have tried to block the fracking at the county level, so far with no success. The U.S. Bureau of Land Management is scheduled to auction off oil leases from a 3,000-acre chunk of shale-rich land in southern Monterey County

in September.

“People don’t understand the problems with fracking,” Craig said, sounding exasperated.

The technical name for the process, Craig said, is chemical injection with hydraulic fracturing with radiological tracing.

“They inject a cocktail full of up to 30 chemicals … and no one knows what these chemicals are,” he said.

Every gas company that fracks uses its own proprietary chemical mix to enhance the fracturing process. Fracking fluid is comprised of mostly water and sand, but around one percent is chemicals used to release oil or gas from the shale.

Venoco described its chemical mix as “acid, friction reducers, surfactant, gelling agent, PH adjusting agent, oxygen scavenger, breaker, crosslinker, Iron Control, Corrosion Inhibitor, and an Antibacterial Agent” in a drilling application submitted to Monterey County.

Environmentalists worry that the chemicals used in the process can seep into and contaminate the water supply. They still have unanswered questions about the practice, including these: What are long-term effects of those chemicals on the environment? Fracking requires a lot of water; will large fracking operations lower the water table? What happens if there’s a fracking chemical spill?

That’s an especially troubling thought, considering radioactive tracers are often used in the cocktail.

Several studies have been released recently linking hydraulic fracturing and natural gas drilling with contamination of groundwater.

Despite such concerns, however, fracking is still going on—but no one is sure as to its extent.

New Jersey’s Governor Chris Christie has declared a one-year moratorium on fracking, a move that likely traumatized his right-wing supporters. New Jersey, however, doesn’t have any areas that would benefit from the drilling practice.

Venoco drilled two fracking wells in northern Santa Barbara County and neglected to tell anyone. The Santa Barbara County Energy Division was unaware the company was secretly fracking within county borders until officials figured it out after the fact. Since there’s no regulation nor law that says a company has to disclose when it’s fracking, Venoco technically wasn’t doing anything wrong.

There have been other instances in other parts of Santa Barbara County where conventional drilling turned out to actually be fracking.

“The technology has developed faster than the regulations,” Craig said. “Can you imagine an industry that pumps chemicals into the ground and we don’t know what they are? The government can’t keep track of it.”

But there have been some efforts to change that fact.

In June, the California Assembly passed a bill that would force companies to disclose the location of every fracked well in the state. The bill, sponsored by Assemblyman Bob Wieckowski, a Democrat from Fremont, would also reveal the chemicals used in fracking, though not the exact recipe. Legislation in Congress titled the “Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals Act” (FRAC) has also been proposed.

Oil speaks

Venoco and other companies declined to speak to New Times for this story.

But Tupper Hull, a spokesman for the Western States Petroleum Association, said fracking is good for California and its people.

Oil production has been declining since the 1980s, and now it may be possible to bring back tens of thousands of jobs, according to Hull, perhaps creating a rejuvenated industry that may benefit all Californians.

“Fracking can certainly be done in an environmentally friendly way,” Hull said. “Fracking for oil is a lot different than fracking for gas.”

Hull pointed out that studies have identified groundwater contamination resulting from gas fracking, not oil fracking. Gas fracking requires constant pumping of water, chemicals, and gas. Fracking for oil, on the other hand, is a one-time operation. Fracking also takes place from 5,000 to 10,000 feet deep, a depth that puts thousands of feet of rock between oil operations and the water table.

“They’ve never found contamination from oil fracking,” Hull said.

Strangely, there was a pessimistic note to Hull’s tone as he flacked for his industry.

“I’m just realistic,” he said when asked about the downer vibe he was giving off. “You have to jump through a lot of hoops to produce in this state.”

Even if Monterey shale can be used, he seemed doubtful that the state would ever allow anyone to get at all the oil that’s there.

“There are 10.5 billion barrels off the coast of California that can be produced in conventional ways,” Hull said, pointing out how much more fracking goes on in less regulated states like North Dakota and Texas—though there is much less oil there. “I don’t know if the state of California will ever let us get the oil that’s in the Monterey shale.”

Back to the future

Geologists have known about Monterey shale for a long time, said Richard Behl, professor of geology at Cal State Long Beach. And Behl knows his shale. He wrote his PhD dissertation on the stuff, and studying it is his life’s work.

The Central Coast was once the biggest oil-producing area in the world.

“All the oil in California comes from the shale,” Behl said. “The oil that is easy to bring up is oil that has been released from the shale and pooled near the surface.”

The Monterey formation had been producing large amounts of oil for more than a century. Conventional oil extraction techniques are still bringing up oil south of Santa Maria and in many other areas in Central California.

Behl doesn’t seem sold on the idea that fracking will open up the Monterey shale as much as many people say it will.

“A lot of the Monterey shale is already fracked,” Behl said.

That’s due to earthquakes and other natural phenomenon. However, Behl did say fracking might be helpful in getting oil from certain areas. And the long-term prospects for large oil production in the Monterey shale are still good.

“It’s an incredibly carbon-rich area,” Behl said. “There is a lot of oil trapped in it.

“It’s just a matter of time before environmentally acceptable methods of fracking or other techniques are developed [and the oil brought up],” Behl said. “Frankly, it depends on the demands of society. If people are starving for oil, that’s going to make people look for oil where they haven’t looked for it before.”

Contact Staff Writer Robert A. McDonald at [email protected].

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023