Taking back a city: A community mourning those lost to increasing gang violence organizes to protect its youth

By Joe Payne[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

The boardroom of the Santa Maria Join Union High School District was packed wall to wall with people on Jan. 28. They gathered there in an attempt to address a dire situation in Santa Maria: an eruption of street violence that’s left young adults and teenagers bleeding in the streets.

It was the first One Community Action Coalition meeting of the new year and included school educators and administrators, local politicians, law enforcement, community group members, church leaders, and concerned citizens—more people than have ever attended the meetings before.

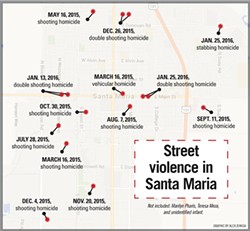

Since the group’s last monthly meeting, on Dec. 17, seven homicides have occurred. Three of those happened on Jan. 25, just days before the most recent meeting. Those homicides included 15-year-old Marcos Ramos, who was stabbed to death that afternoon not far from his school, Pioneer Valley High. Later that night, a double shooting left Alexis Morales, 25, and Augustin Montano-Barajas, 29, dead.

In January and the last week of December, Santa Maria experienced more than half the number of homicides committed throughout 2015, a year that broke records for violent murders in the city.

Tense comments and questions opened the meeting after Santa Maria Police Department Sgt. Russell Mengel addressed the group to provide an update, sharing what information he could about the cases.

A junior high school administrator complained that “what’s out on the streets is mirrored at our school.” An organizer with a community group shared that she’s been receiving reports from parents that kids are getting jumped on their way home from school and sports activities. She asked what the department was going to do about it, insinuating that recently increased patrols might disappear after a few weeks.

The meeting’s last comment came from a self-described “concerned citizen.” After describing his experiences living in Greenfield and the organizational efforts made there to curb youth violence, he made a clear and impassioned declaration.

“I’m a Catholic, and I like to go to St. Mary’s, and I’m afraid to walk into church at night with all the crap that’s going on,” he said, referring to the proximity of the latest shooting to the church.

“I don’t pack a gun, but I will be packing a gun, legal or illegal. I’m just going to have one,” he continued as the crowd rumbled with talking and some nervous laughter. “If someone threatens me, I’ll shoot ’em. It’s getting to the point where it’s time to take our town back from the gangs, and I’m adamant about it.”

Sgt. Mengel replied to the statement calmly, while addressing the emotion behind it, saying that citizens need to act safely and legally, lest they compound the problem at hand. Over the last 11 months, Santa Maria has seen a steady rise in street violence, with the explosive increase in January plunging citizens into fear, anger, and desperation to see the killing stop.

Dealing with the ordeal

Santa Maria Police Chief Ralph Martin didn’t mince words when he sat down to talk with New Times two days before the coalition meeting. The appointment was made a week in advance and was kept, even though the station was buzzing with personnel, visitors, and media dealing with the repercussions of the day before—Jan. 25, one of the deadliest days in Santa Maria’s history.

“I would say that it appears that there’s been a level of increased violence. About 60 percent to 70 percent of our homicides are due to gang members or gang associates, so there’s definitely retribution going back and forth,” he said. “So, I don’t know. ‘War?’ That could be a drug war, a turf war, whatever you want to call it. I don’t give them any credibility by saying their names, but clearly, there is a battle going on between some of our local street gangs.”

The SMPD and Martin have been the subject of criticism at Santa Maria City Council meetings during public comment, in comment sections of local media reporting online, and on social media, blaming the department for not doing enough to address the problem or make arrests.

Of all the shooting homicides from the last 11 months, the SMPD has yet to arrest or charge anyone for the crimes. There’s good reason for that, Martin argued, pointing to the character of the attacks, the speed with which they were executed, and the quality of evidence available to the department.

“In my business, it’s not what you know, it’s what you can prove, and if I can’t take it to the DA [district attorney] and get a case, then I’m spinning my wheels,” he said. “I’ve always said I get fear and apathy, but unless the public helps us, we’re not going to be able to do our job. We had officers on the scene of that double homicide last night within almost a minute; the gang suppression team that was out there heard the shots.”

Martin explained that he couldn’t say when arrests would be made, but that he was confident they would happen soon. He urged the public to be patient despite their fears. The greatest contribution to investigations is citizen testimony, Martin explained.

Santa Maria isn’t necessarily a unique case right now, Martin said at the recent One Community Action Coalition meeting, pointing to spikes in violence in cities larger than Santa Maria with similar demographics.

“What we’re seeing in Santa Maria is also occurring in other cities,” he said. “For instance, in Salinas there were 15 homicides in 2014; last year they had 40. Bakersfield has had 22 homicides since July 22 of last year, and we’ve seen a spike in Oxnard. We don’t have rhyme or reason, but we have gone to outside sources, we’ve reached out to our federal partners to do crime analysis.”

SMPD works with federal agencies, as well as law enforcement departments that are close by—both the Santa Barbara County and San Luis Obispo County sheriff’s departments. While cities in Santa Barbara and Monterey counties have seen an uptick in homicides related to gang violence, SLO County remains a relatively quiet pocket of peace.

“In all cases, we share communication as much as possible,” SLO County Sheriff Ian Parkinson told New Times. “We haven’t seen much bleed-over yet, but that’s what’s troubling to us.”

Parkinson said there is definitely gang activity happening in the county, and the Sheriff’s Office keeps an eye on things through city police departments and the county’s gang unit. He said the activity in South County—mostly in Nipomo and Oceano—is through “homegrown gangs” with local ties, unaffiliated with larger gangs.

“In the last few years, we’ve identified Northern California gang members in North County, and that’s where our concerns lie [up there],” he said.

Parkinson said if he had to venture an extremely educated guess, he would say that a lot of the gang-related issues in Santa Maria haven’t grown into the South SLO County area because the draw isn’t there. Moving from a populated area of more than 100,000 people to the small-in-comparison towns of Oceano and Nipomo just isn’t appealing.

Although, there was a gang-related homicide in Oceano about four years ago, Parkinson said. Alleged former Los Angeles gang member Armando Yepez of Santa Maria got upset with some Nipomo gang members and randomly shot at a group of teens standing on the street. Gabriel Salgado, a 17-year-old with no gang affiliations, was killed. Yepez was successfully prosecuted, but Parkinson said it wasn’t easy.

“Even though their friend was killed right in front of them, the cooperation level was zero,” Parkinson said of the group of teens. “These cases are extremely difficult to solve, and the reason why is because nobody comes forward. … It took us a number of months to be able to develop leads and be able to make arrests and prosecute that case.”

He said there are generally two reasons people choose to keep their knowledge to themselves: fear of backlash and street code, which means gangs prefer to carry out their own form of justice. As far as the recent Santa Maria homicides go, Parkinson said he’s seen Chief Martin imploring the community to come forward with information.

“In most cases we know that members of the community know,” he said.

Community members coming forward with information could be the best shot that law enforcement has to make an arrest and successfully prosecute a case.

What’s been happening in Santa Maria over the last several months isn’t the norm. According to Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) statistics available on the SMPD’s website, Santa Maria’s homicides didn’t exceed four a year from 2009 to 2014, with the exception of 2011, which had seven homicides. According to Martin, national yearly averages show four homicides per 100,000 people.

“This is targeted,” he said. “It’s one thing to kill somebody, but the savagery with which these people are firing rounds, I mean, my God, they’re using machetes. … This is savagery, and we’ve never seen this before in Santa Maria.”

Law enforcement needs to be aggressive in these cases, Martin explained, so that gang members know there will be consequences to pay. In the case of the two suspects apprehended in connection with the stabbing of Marcos Ramos, both received gang enhancements on all charges, and the unnamed 14-year-old suspect is being tried as an adult.

Even given the severity and level of violence, Martin said that a small minority of the population is actually responsible for the crimes and that the SMPD detective bureau is working tirelessly to track down the perpetrators. It’s a grueling battle, and law enforcement feels the gravity of these situations acutely, Martin explained at the recent coalition meeting.

“They [the suspects] were somebody’s little boy at one time and we know that, we know that, and it chokes us up,” he said as the audience murmured in emotion. “And I want you to know that these detectives are working as hard as they can. They are taking it, I don’t want to say personally, but this is our city, this is our town, and we are going to solve these cases.”

Finding the factors

The One Community Action Coalition was assembled last year around September at the behest of the Santa Maria Joint Union High School District Director of Student Services Peter Flores, who reached out to Michael Fuentes, the program coordinator for the Santa Maria Youth and Family Center. Fuentes organized a group of colleagues from local support nonprofits, members of the faith community, and even some youth he’s counseled.

Fuentes and his colleagues and friends have years’ worth of experience in gang intervention, counseling at-risk youth, and providing positive outreach. Getting everyone together, he explained at the meeting, was just the first step in addressing the problem in a comprehensive and holistic way.

“What we talked about was what we need to do in order to try and get our kids to do something different,” Fuentes said. “This is about the gangs getting stronger and what we need to do to address it, whether it be at the elementary level, the junior high level, or the high school level.”

Tally up the year’s worth of homicides, and more than a quarter of victims are minors, close to a third are younger than 20, and the majority are younger than 30 years old.

The issue affects the youth disproportionately, which is why the One Community Action Coalition is especially dedicated to youth outreach and intervention. Prevention isn’t enough, several founders argued. It will take intervention along with a fundamental reappraisal of how schools and law enforcement deal with the youth.

“One thing we notice about a lot of these kids is they’re beat up, and I mean beat up emotionally, … because not only are they abused at home, but they are abused in the school system and by law enforcement,” Fuentes said. “We’re not here to point the finger, we’re here to communicate with each other and figure out what we need to do to take back control of our children.”

The answer to the problem, Fuentes said, is in mentorship, in truly being there for kids, no matter how far gone it may appear that they are.

The guest speaker at the Jan. 28 meeting was Richard R. Ramos, an author and educator with decades of experience in gang intervention in communities like Los Angeles and Santa Barbara, where he lives. He was called to speak after the Jan. 25 stabbing death of the Pioneer Valley High School student, who was actually a student of his brother Tony Ramos.

He told the coalition that the most important assets in communities are parents—solid parenting is the greatest inoculation young people can receive against the allure of street gangs. He shared a story from the youth outreach and gang intervention he’s done in Santa Barbara. A grandfather asked Ramos to talk with the kids and give them his perspective on a life of violence.

“I said, ‘You’re a gardener by trade, so let me tell you in a way I know you’ll understand,’” Ramos said. “If you were to walk down the street here in your neighborhood and you were to look in the yard of every home and you saw that all the flowers were wilted and dried, who would you rather spend time with, the flowers or the gardeners?”

Ramos’ book Parents on a Mission is also a six-week curriculum he teaches to equip parents with the tools they need to keep their kids safe and supported enough to withstand the peer pressure of gangs, violence, and drugs.

For counselors like Fuentes and his colleagues, the reality is that quite often they are the most stable adults in the lives of the youth they mentor. And that’s the key, they argue: consistent mentorship, showing the most troubled youth that somebody cares about them.

One of the youngest founders of the coalition is Ramon Gallardo, who grew up surrounded by the gang lifestyle. Growing up without a father, Gallardo looked up to his older brother, who sold drugs and often had Gallardo “test the product.” Gallardo spent hours in counseling with Fuentes, but saw him as “the enemy.” It wasn’t until Gallardo served jail time that he realized who really cared about him.

“Most of the time he would just get down to my level, showed that he cared, and I never forgot that,” Gallardo told the Sun. “When I was in juvenile hall, and I would get a visit, it was Michael Fuentes, and I was like, ‘What is this guy doing?’ He was at all my court dates; he just cared. When I got out of prison, the first person I went to go see was him, because he showed he cared, showed he was there, and he was real.”

Hope and healing

The weekends following the Jan. 13 double homicide and the murders of Jan. 25 saw large community prayer walks, the first led by Foursquare Church and the second led by Victory Outreach, which focuses on reforming gang members and drug addicts with the help of faith.

Ramos, who spoke with New Times following the coalition meeting on Jan. 28, explained that a number of factors lead to street gangs, including poverty, racism, and drugs. But when it comes to helping those imbedded in the culture of the gangs, the faith community is especially powerful, he said.

“I didn’t say this during the meeting, but the most effective methods I’ve seen of transformation for individual gang members is the faith community,” Ramos said. “They’re really able to get in, as they say, and do the inside-out work that other methods are not able to do.”

Most of the founding members of the coalition credited the churches and programs they are involved with—including Revival Tabernacle Church, Victory Outreach, Fighting Back Santa Maria Valley, and others—as vital influences in their lives. Gallardo described the relationships formed between gang members as an “illusion,” and pointed to the bonds made in faith communities as the real connection he was looking for.

Another young reformer, Joseph Ramos, explained that young people could find friendship, mentorship, and stability at the church, but also through the dedicated counselors who stay consistently connected with troubled kids, whether they’re clergy or counselors.

“A lot of these kids, the dads walk out on them, the moms are gone, so there’s separation issues,” he said. “You want someone that you can depend on, count on, someone that’s anchored in your life, a focal point, a big old sturdy rock like the one they have out there in Morro Bay; it’s there, it’s always going to be there, and you can go to it anytime you want.”

Most organizers and representatives at the meeting agreed that the problem can only get better when the variety of diverse organizations and citizens come together to help address the problem.

“I don’t see anyone pointing the finger, everyone wants to be proactive,” Santa Maria Mayor Alice Patino told New Times. “They acknowledge the problems we have in the community, and they want to get in there and help it, help solve the problems. I am thrilled that we have so many people from so many different areas of the community willing to commit themselves to making Santa Maria a better place to live.”

The One Community Action Coalition’s next meeting is slated for Feb. 18 and will be open to the public. The organizers hope to offer another general presentation before breaking into groups to provide education for the sectors involved, including law enforcement, educators, counselors, faith leaders, and parents.

The problem won’t disappear overnight, Fuentes told New Times after the Jan. 28 meeting, but when faced head on, it’s an issue that can be assuaged.

“There’s a lot of things that need to be done, and if we all put our heads together and get trained in the right areas, and we take that training and practice it, then we’ll be able to reach so many kids that people will be amazed at what can happen,” he said. “It’s going to take this community to come together, bond together.”

Contact Arts Editor Joe Payne from New Times’ sister paper to the south at [email protected]. New Times Editor Camillia Lanham contributed to this article.

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Coast Unified teachers upset over new position's salary and qualifications

Oct 20, 2022 -

SLO police identify alleged driver who hit and killed couple

Dec 22, 2022 -

When the levee breaks: Oceano residents, county officials walk a tightrope of regulations to manage Arroyo Grande Creek, which some say led to the levee's failure in January

May 18, 2023