[{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle CC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "8",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC01 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleCC01300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "18",

"component": "2963441",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "22"

},{

"name": "Ad - Medium Rectangle LC09 - 300x250",

"id": "AdMediumRectangleLC09300x250",

"class": "inlineCenter",

"insertPoint": "28",

"component": "3252660",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "32"

}]

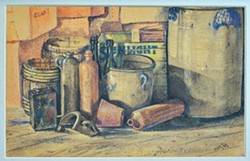

The earliest work in the current exhibit “Nico Vandenheuvel: Then and Now,” a small still life called Attic Corner, is dated 1947. The most recent works in the show were painted in 2013.

One would be hard-pressed, however, to date the 25 works in “Then and Now”—which hangs at the San Luis Obispo Museum of Art (SLOMA) through Feb. 2—by style alone. Some of the Dutch-born artist’s paintings from the past year look like they were done by a contemporary of Georges Braque, while many of his works from the ’50s were rendered in a then-unpopular style Vandenheuvel dubbed abstract surrealism. Other works—some contemporary, some from early in the artist’s career—pay homage to the Old Masters. Vandenheuvel has not only transformed his art practice many times; he’s also revisited styles and subjects over the years, making it his paintings nearly impossible to place within a timeline.

Vandenheuvel’s solo show in the McMeen Gallery was granted after he won “Best in Show” at SLOMA’s 2013 “Brushstrokes” exhibition. The result, “Then and Now,” is a stunning and eclectic offering—if a little crowded.

What has transpired between Then and Now is a strange and wonderful story. It’s one of vagabonds and beatniks; of youthful rebellion and artistic reinvention. Had Vandenheuvel but slowed down for a minute; had he lingered in one place and one style for a little longer, he might have become a household name.

But Vandenheuvel, 85, born in Rotterdam and based in Cayucos, has always followed his own path. Largely self-taught, he dropped out of high school in favor of seeing the world as a steward with the Merchant Marines. In Toronto, he says, he jumped ship, finding menial work in Canada until he was eventually apprehended by the immigration authorities. Back in the Netherlands, Vandenheuvel was drafted into the military, where he served as a topographical draftsman. He later took up several odd jobs—including a stint working for a private detective, and a gig painting theater backdrops—before hitchhiking to Paris.

After being apprehended by the Belgian highway patrol on his first try, he made it to the City of Lights on his second, and proceeded to live the life of the penniless artist.

Vandenheuvel, whom I met for coffee following the installation of “Then and Now,” describes this time in his life with a clarity and matter-of-factness coupled with a particular flair for the parenthetical. Vandenheuvel even recalls the Belgian holding cell, in which he stayed for two weeks, almost 60 years ago, with startling specificity:

“I talked to the watchman there … I said, can I have my tools back, I’d like to paint. So he gave my backpack back, with everything in it—including razor blades!—and so then I set up the furniture in the cell—it was a nice cell; it was actually a room with a parquet floor. It had cold water; no hot water. A private corner there, with a chamber-pot, cast iron, about that high …” (There followed an explanation of chamber-pot mechanics.) “The furniture was beautiful, just old fashioned, simple furniture, like folk art, almost … ”

Even though he’s lived in California since the late ’50s, his Dutch accent persists, lending a musical quality to everything he says.

He received a lift to Paris from the driver of a meat truck, the artist explained, on the condition that he help unload frozen cow carcasses on arrival. Vandenheuvel described his initiation into the bohemian lifestyle he would lead for the next four years, ironically sponsored by the U.S. Army.

“I helped the guy unload, and then I found a place to sleep, outside of course, in these wood-pulp things—shavings! And that was the beginning of my life in Paris. I tried to sell linoleum prints [to tourists], and it was pretty good, I made my meals with that, Arc de Triomphe and all these places. Sacre Coeur. So I did that, and then after a while I was needing to find a better place to sleep. It was getting cold. It was getting winter. So I slept under the bridge Pont Neuf with a bunch of other clochards, as they called them. Bums. In the morning I was starting to paint on the Seine, which was right there, and some guy tapped me on the back, and he had an American Army uniform on—1954, it was—and he said, ‘If you can do a poster in 20 minutes, we can hire you.’ I wanted to play hardball, so I said, ‘How much money?’ I had nothing, you know. He said, ‘Let’s first see if you can do the poster.’”

Vandenheuvel was hired to illustrate posters for Army events. The four years in Paris were good to him. He painted. He met Man Ray. He also met his wife, Dory. In 1958, the two moved to Venice, California, where they opened Gallerie Nico.

Vandenheuvel has saved a great deal of the articles that have been written about him and his work, and surprised me by bringing photocopies of them to our interview. The first are in Dutch. Then one in French. Then a 1959 article from Time, which hails Venice as the new beatnik hotspot. (Vandenheuvel and his artwork are featured.) “Beach Era Fades,” proclaims the next article, lamenting the closing of the iconic Beat hangout The Gas House, and a general exodus of the Beats from Venice. (“It’s enough to make an existentialist buy a house in the suburbs,” the writer mourns.) Yet there appears to be hope in Vandenheuvel’s decision to stay in the neighborhood, according to the article. (“The presence of Nico … is a vote of confidence for a better Venice to come.”)

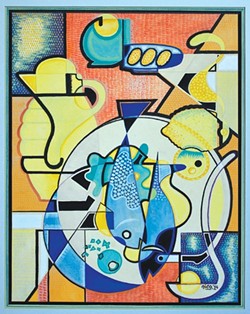

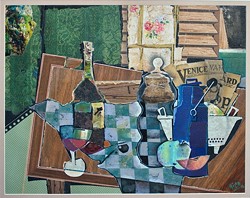

Around this time, Vandenheuvel was experimenting with artistic styles from both sides of the Atlantic, as his SLOMA exhibit shows. Presented in a retrospective fashion, “Then and Now” reveals a perpetually restless spirit, vacillating between styles with abandon. From the ’50s alone, we have the Cubist-influenced Still Life with Pitchers and Sannois Studios, the abstract expressionism of Condemned Area #5 and Eccentric Motion (the latter taking a cue from Franz Kline), and the aforementioned “abstract surrealism” of Cactus Man.

The notion of “abstract surrealism” is worth considering. It sounds like a buzzword; something that should already exist in the artistic lexicon. Yet Vandenheuvel seems to have totally made it up, in order to describe the fluid, suggestive oil paintings he made in the late ’50s and early ’60s. Unfortunately, works like Cactus Man found little critical favor at the time, as Vandenheuvel pointed out during a brief talk at the show’s reception. “Abstract” works in this era could either be blocky, angular, and deliberate or splashy and spontaneous—a definition that left little room for Vandenheuvel’s fleshed-out, sensual, ambiguous pictures; works with the muted palette and form of Surrealist paintings, yet abandoning any representational elements.

From Venice, Vandenheuvel moved to Topanga and eventually settled in Cayucos. As the exhibit shows, he continued to reinvent himself throughout the years. When he did return to well-trodden territory, it seems, he did so with a new sensibility. The still life, for example, is a recurring motif in “Then and Now,” yet the technique used to capture it varies widely. In recent works have appeared the deconstructed glasses, bottles, newspapers, and musical instruments favored by Picasso and Braque, while those from just a few years earlier are straightforward and representational.

Vandenheuvel has long toyed with a technique of letting paint drip over paper or canvas, then coaxing faces and figures out of it. (He still owns the piece he created this way as a vagabond in a Belgian holding cell.) Another example of this technique is Waiting, a work from 1971 in which a woman’s face seems to organically emerge from a chaos of color.

Upon entering the exhibit, viewers are greeted with the bold yet simple geometry of Coming Together, which hangs at the top of the stairs leading to the McMeen Gallery. Other works from the early 2000s line the stairwell, making for an unfortunately rather cramped and ill-lit viewing experience on the way to the main event. The work is great, of course, but the exhibit would have been improved by the omission of these pieces.

The paintings aren’t given much room to breathe within the gallery space itself, either, but one immediately sympathizes with the curatorial challenge of singling out pieces from such a diverse and lengthy career. Each one seems to represent an entire body of work; an entire personal reevaluation. “Then and Now” is so varied, it could pass for a group show.

Speaking with Vandenheuvel, now a respectable elderly gentleman, it’s hard to picture the wandering, penniless vagabond of the ’50s, or the Beat artist of the ’60s. But it’s there in “Then and Now,” in the earnestness of Attic Corner, the youthful abandon of Eccentric Motion, and the sensuality and daring of Cactus Man.

Arts Editor Anna Weltner was writing bad poetry by the creek with the clochards when New Times tapped her on the shoulder. Contact her at [email protected].